During my visit to Chicago’s Axpona 2023, I had the privilege of interviewing Chad Kassem, owner and founder of Acoustic Sounds, Analogue Productions, Quality Record Pressings, and Blue Heaven Studios. Chad was very generous with his time and spoke candidly about his life, aspirations, and the numerous challenges he faced while building his thriving enterprise.

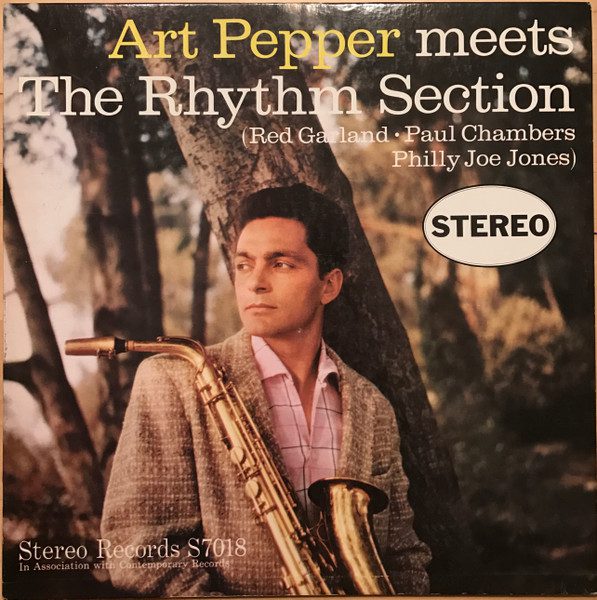

Chad is a significant figure in the audiophile community. His reissues under the Analogue Productions label that I’ve purchased over the past two decades are some of the best-sounding records in my vinyl collection. Chad’s relentless pursuit of the highest quality reproduction of music on vinyl has played a crucial role in the medium’s revival.

I met Chad early in the morning for our conversation. I began by inquiring about his background, including his origins, teenage years, and how he ended up in Kansas.

“Well, I’m a half Cajun. My mother speaks French, and the family spoke French, and a lot of people in Southwest Louisiana still do because it’s where the Cajuns that came from Nova Scotia ended up. It’s a very unique part of America. The culture is just so different. They have their own language, their own music, their own style of food. And that’s where I was raised. One thing about the Cajuns and people from Louisiana is they like to have fun.”

I told Chad that I’d been to New Orleans so I had an idea of the fun he was talking about.

“New Orleans is a bit different than where the Cajuns are,” he said. “The Cajuns are really in Lafayette, west of New Orleans. Now, New Orleans has this. There are a lot of similarities. But if you want to find where the most Cajuns are, go a little further west.

“When I grew up in Lafayette, bars were open 24 hours. You could buy beer at 12-years-old. Lots of drugs and a lot of festivals. Every weekend there’s a festival: crawfish festival, crab festival, shrimp festival, jazz festival… any excuse to have a party. And the weather is warm, so people don’t really sit at home and listen to records. You can hear live music so often that you don’t stay home.

“[If you’ve only ever lived there], you don’t recognize how unique of a place Lafayette is. You think everywhere is this way. Everybody does this. You have to move away to realize how different and how special it is.

“There are so many musicians. The families pass it down. I learned so much about the history of New Orleans music. Rock ’n’ roll pretty much started in 1949 with Fats Domino. A lot of people think [it was] Little Richard or Chuck Berry. No, Little Richard [who hailed from Georgia] went to the studio in New Orleans, and it was with New Orleans backup musicians that he made his best hits. I’m not taking away anything from Little Richard. He’s awesome. And he was at the beginning for sure. But I learned all about the blues, zydeco, and jazz, from where I was from.”

Chad paused a moment, then said: “I got in a lot of trouble. [At one point], I had to choose between going to jail or to a halfway house. This was around 1984, so I was about 22 years old. It wasn’t a hard decision to pick a halfway house over jail. The only problem was that the halfway house was in Salina, Kansas, exactly in the middle of America, which couldn’t be more different than where I was from. But that’s exactly where I needed to be. A place that doesn’t have a lot of alcohol, where there’s not a lot of misbehaving, where the bar closes, things like this. So, I moved there.

“This is the year that CD was coming out, 1984. I get to Salina, Kansas, and I’m staying sober. I got a job right away. I was working hard, trying to do as good as I could. I wanted to start putting my record collection back together. My dad called me. He said, ‘I’m coming to Kansas, is there anything you want me to bring?’. It’s about an 11-hour drive. I think he’s bringing me a car! I said, ‘Well, bring my stereo and my records.’

“He brought my stereo, my records, which was a lot of my identity, from when I was partying and carrying on. The records had scratches and dust. I started replacing the bad ones.

“After, I went home to Louisiana to visit a friend who was an audiophile. We were both music lovers, but he’s a bit more of an audiophile than me. And he learned so much about how to set up turntables and about tubes and the different kinds of brands. And he really went far into it. I went to his house, where he showed me records that said ‘Original Master Recording’ on the top, and some that said ‘Super Disc Nautilus’. And I said, ‘Well, Chet’ — his name is Chet — ‘I have some of those already. I don’t hear the difference [with regular recordings]. To me, they sound the same. He said, ‘Sit in the middle of the bed right here, I’m going to put one on. Now you got to listen very subtly. It’s not going to slap you in the face. The band is not going to jump out of the speakers and start playing live! It’s subtle. If you listen carefully and you listen to these sorts of things, you’ll hear the difference. But you have to sit in the middle.’ I’m like… okay, whatever… I sit in the middle. I start talking. He said, ‘Chad, listen, you’re never going to hear if you don’t shut your big mouth! All I’m asking is one song! Don’t say nothing and sit in the middle.’ I said, ‘Okay, I’ll give you the song.’ And he played it. I heard the things that it did good. When he told me how rare these recordings were and how much they were going for and how they’re hard to find, it was a lightbulb moment!

“When I get back to Kansas, I go to the record store — we had a nice record store in this little town. And they had a shitload of these out-of-print records. I called my friend and told him, ‘They have the UHQR Dark Side! They have the UHQR Sergeant Pepper! They have Déjà Vu! They have all the Zeppelins!’ He bought a bunch of them. And then I took the rest and started to collect records.

“I went all over America. Every time I was in a big town, I would go to every used record store. They still had new record stores in the malls. CDs were just coming out.”

He squinted, then said: “Do you know how they tried to kill the record? People don’t realize how that really happened. It wasn’t because the CD was better. There were two reasons. First, the record labels blinded people with science. People looked at that silver disc and they thought it just had to be better. It was quiet. There was no ticks and pops. And so, your mind told you it was better because you’re blinded by science. It was such an invention. You could play this little silver disc.”

“It was the future!” I said.

“Yeah, it was the future,” Chad says. “But at that time, I was buying every record I could. So, the whole world was going towards CDs and I’ve been swimming in the opposite direction since 1984. There were only a few people I can remember that were championing records and Michael Fremer was one of them. There were a few others, but there’s also a lot of Johnny-come-latelies. They’re coming back to the party. And we’ll welcome them back, but they were the first ones I saw running. They’re now telling me. ‘I’ve been supportive!’ Yeah, you can tell somebody else that. They may believe you, but I remember.

“The other reason the CD almost killed off the LP is because, before the CD came out, if you were a mom-and-pop store, you could order all the LPs you wanted and if you had a defective one, you could return it. If you had overstock, you could return it.

“Let’s say a new band came out, a funny name you never heard of. Well, people who owned the stores didn’t know about the newest crazy music, so they were reluctant to buy more than a couple of copies of it. But the record label would say ‘It’s popular and people are going to come in for this record. It’s hot. And if you don’t sell it, you can return it.’

“That’s how the labels got the stores to buy more records, because you need to buy the new artist but you don’t want to lose money. Well, when CDs came out, they said, no return anymore for defective vinyl for any reason. It’s a one-way sale. And we’re going to raise the price of records by a dollar and lower the price of CDs by a dollar. And you can return CDs all you want, for defects and overstock. That’s why you had a record store in ‘84 that was 100% full of records, then 95% full of records and 5% full of CDs, and within a year and a half it had gone to 95% CDs, 5% records. That’s how that happened so fast.”

Chad’s love for blues music began at a young age. I asked what drew him to this genre, and if it was his favourite.

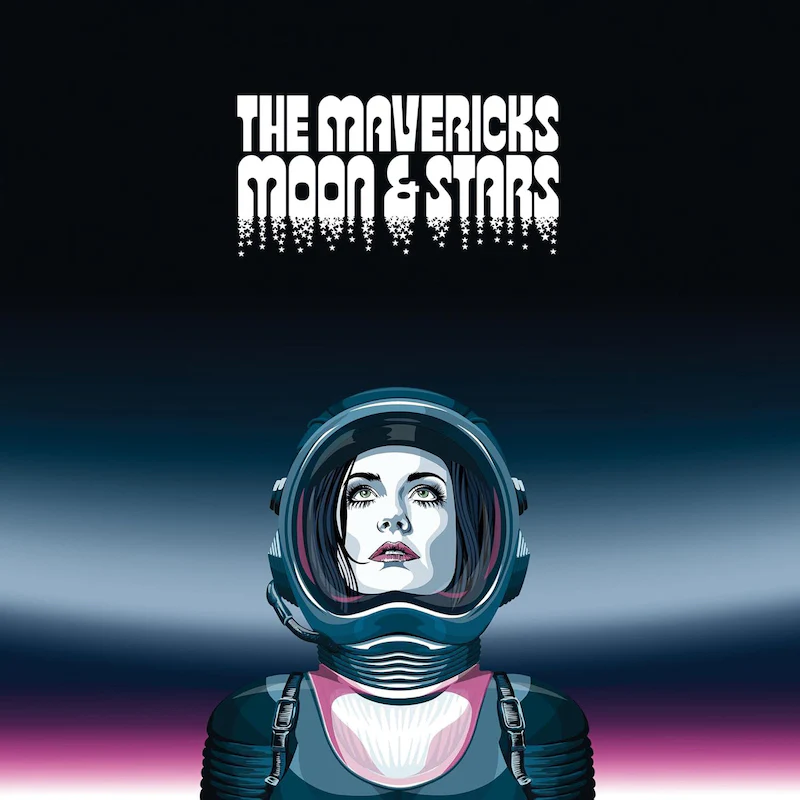

“Yeah, it kind of is,” he replied. “I love blues. To me, blues is like classical music — it sounds as good today as it did when it was made. It’s the same way with most jazz. And then blues, to me, is the foundation of the music that came after — rock ‘n’ roll, R&B, jazz. I tend to like jazz when there’s blues in it.

“And I like music that sounds good. If it doesn’t sound good, I like it less. I want something that draws me in. [I like] a lot of air and spaces between the notes. If it’s loud and compressed or too busy, it’s not enjoyable to me.

“I like more natural, more acoustic, less dated-sounding music. And blues is one of those styles. I also love classic rock, especially when Zeppelin or Foghat or the Allman Brothers are doing blues. I love the original songs from Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf and the same songs in their rocked-out versions. I love jazz and classical. But again, if the music gets too heavy or too busy…”

“Like free jazz or experimental?”, I suggested.

“Yeah. Some of that I don’t care much for. If it’s too busy, if it’s too loud, if there are no spaces, it’s pointless for me to listen to.

“Growing up in Louisiana, you got jazz coming out of New Orleans. You got the rock ‘n’ roll of Fats Domino and all that. So many hits came out of New Orleans. So much music was influenced by music from Louisiana. There’s a lot of blues, Cajun music, and then there’s zydeco, which is a mixture of R&B and Cajun, where they play the accordion and the rubboard. And they sing in French. A lot of the bands we know will go to France and tour. One of our bands that was famous is Zachary Richard. Have you heard of him?”

“I know him very well,” I said. “He’s very popular in Canada, particularly in Quebec and New Brunswick.”

“Well, he dated my mom,” Chad continued. “His nickname is Ralph. We had all these influences, and a lot of it is blues-based. I also tried to document the blues. These blues guys are older, and they’re dying.

“There’s two things I tried to do: keep blues alive and keep vinyl alive. These are two big goals of mine and I did what I could. But most of the blues masters are gone. Taj Mahal is still living. So is Charlie Musselwhite, Billy Boy Arnold, Buddy Guy. Buddy is from Louisiana. He’s 86 now.”

Read Part 2 here.

Leave a Reply