This article first appeared in PS Audio’s Copper Magazine.

Getz/Gilberto is one of the most well-known and well-loved jazz records of all time. Rightfully so: the 1964 Verve release by Stan Getz and João Gilberto is one of the best-selling jazz albums ever, the musically brilliant recording that made bossa nova popular worldwide. Getz/Gilberto would have been assured of legendary status just for one song: the iconic “The Girl From Ipanema,” sung to vocal and emotional perfection by Astrud Gilberto. But the record is so much more than that, with classics like “Corcovado,” “Desafinado,” and more. Yet it almost didn’t get released, thanks to a Verve executive who thought bossa nova was past its prime. It took the personal promotional efforts of Getz’s wife Monica get the album produced.

The album features Getz on tenor saxophone, João Gilberto on nylon-string guitar and vocals, Antonio Carlos Jobim on piano, drummer Milton Banana, and Astrud Gilberto singing on “Ipanema” and “Corcovado.”

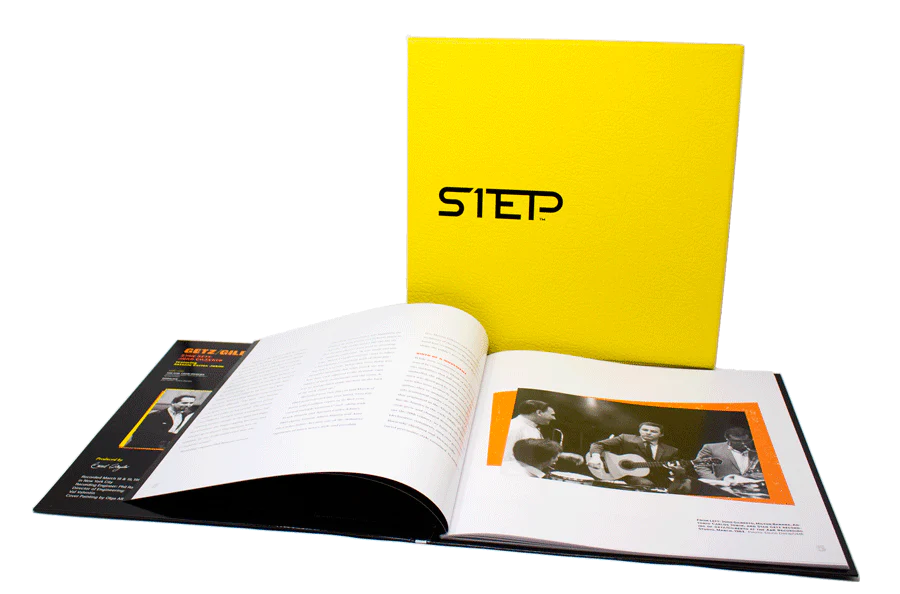

I won’t waste words: this Impex 2-LP 45 RPM 180-gram vinyl reissue is simply magnificent. The fold-out LP set comes in a heavy textured slipcase, and the LP cover is beautifully printed on heavy glossy stock. The inside contains a 35-page booklet with the original Getz/Gilberto liner notes, photos, and an absolutely fascinating essay on the making of the record by author, producer and music historian Charles L. Granata. The LP surfaces are silent and the sound quality is sublime. The reissue includes two bonus tracks: a mono single version of “The Girl From Ipanema” and a live recording of “Corcovado” from a 1964 Carnegie Hall performance. This set isn’t inexpensive (it’s selling at Elusive Disc for $129.99), but if you decide to go for it, I don’t think you’ll feel like you didn’t get your money’s worth.

Getz/Gilberto was recorded on March 18 and 19, 1963 by engineer Phil Ramone. As the liner notes point out, the album had an “audiophile” sensibility from the beginning. Ramone stated, “I realized how special these musicians were and how important it was to keep tape hiss to a minimum. So I wanted to run the master recorders at 30 inches per second – double the standard professional [15 ips] recording speed – to pick up more musical information and cut down on tape hiss during the quiet passages. I didn’t want to tamp down any of the clarity or intimacy…and recording it at 30 ips helped put some ‘air’ in there.”

The vinyl was mastered by Bernie Grundman using the original two-track stereo production master and is completely analog. The Impex 1Step vinyl manufacturing process eliminates the usual three-step father/mother/stamper process in favor of a one-step process, where the lacquer off the cutting lathe is plated and the plated disc is used as the stamper.

In order to preserve the all-analog nature of the recording, a couple of sonic anomalies are present. As associate producer Bob Donnelly notes, when the production master of Getz/Gilberto is compared to all subsequent versions (until 1980), the left and right channels are reversed. Whether this was intentional or accidental is unknown and impossible to find out. Also, there’s a tape edit at the first chorus of Getz’s solo in “Ipanema,” and some distortion on the bass in “Corcovado.” Rather than “fix” these flaws in the digital domain, the production team decided to instead leave them in in the effort to offer the highest-resolution representation of the original master tape.

I’m tempted to be lazy here and simply quote Charles Granata as my review: “The magnificence of this 35 minutes of pure brilliance is such that any observations I could distill into words would be superfluous and pale in comparison to trusting your own ears and emotions.” But I’ll give it a go. Getz/Gilberto is one of those rare albums that simply sounds pure and right and is a perfectly-realized work of art, like the Mona Lisa or Miles Davis’ Kind of Blue or Pink Floyd’s The Dark Side of the Moon.

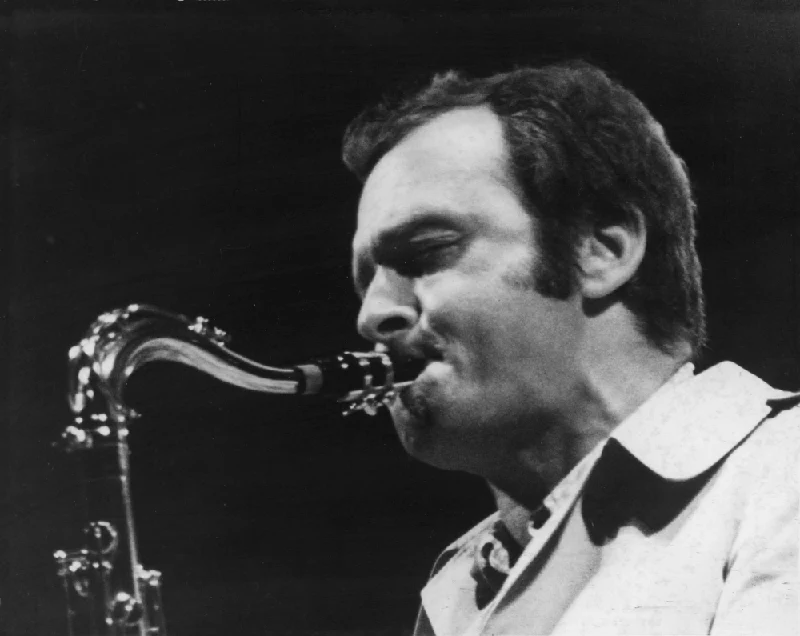

The instrumentalists play with an empathy that could honestly be called musical perfection, like one multi-bodied entity rather than four musicians trying to hurriedly navigate their way through charts. Everyone leaves space for everyone else. Gilberto’s plucked bossa nova rhythms are soft, but absolutely drive the music, and his rich, close-miked voice perfectly suits the songs. Jobim delicately weaves his piano in and out, and Milton Banana’s hi-hat work alone provides subtle yet commanding propulsion. And what can one say about Stan Getz, one of the most beautifully melodic sax players ever, with such warm tone and lyricism, that wouldn’t be overflowing with superlatives? During a time of ever-more-frenetic free jazz players, Getz bucked trends, followed his heart, and never strayed from his less-is-more approach.

At first, Getz was skeptical of having Astrud Gilberto sing on the record. “Are you crazy? She’s not a professional!” he told his wife Monica, who thought her voice would be perfect. Then they ran through “The Girl From Ipanema” in a rehearsal, and Getz was convinced. The rest, as they say, is history.

I’ve owned an original Verve pressing (catalog number V6-8545) for decades and it sounds excellent, with good tonality and “air,” though, like many jazz recordings of the era, many of the instruments are panned to the left and right. Even so, you still get a credible sense of spaciousness.

The Impex reissue absolutely trounces it, as well as the many versions I’ve heard on streaming audio. (I haven’t heard the Analogue Productions reissue, and Discogs lists 673 vinyl versions out there.) It has a warmer tonality with much more vocal and instrumental presence and depth. There’s more detail and subtleties like the harmonics of the guitar or the variations of the brush strokes on the high-hat. Quite simply, there’s more of everything that musically matters. My first listening notes for “Ipanema,” the first album track, are: “Bass – wow!” and “The presence on his vocals – ridiculous!” (It must be said that the stand-up bass sounds a little boomy and soft around the edges, but this is how the original recording sounded. I think Phil Ramone was going for thump, not bright spotlighting.)

There’s a subtle reverb on Astrud Gilberto’s voice I hadn’t noticed before (the liner notes explain that Ramone’s use of reverb was very deliberate and thought out). Gilberto’s piano is now a distinct entity with body and weight, not some hazy noise in the background. You can really feel as well as hear the fact that Jobim is plucking the nylon strings of his guitar with his right-hand fingers, in the classical-playing style. In the Impex pressing, you can hear the subtle variations of his attack, and the subtle rhythmic push-and-pull of his guitar and vocals.

Getz’s tenor sax sounds marvelous. The breathiness and, well, the fact that there’s spit in the horn aren’t subtle colorations; they’re part and parcel of his sound. The presence of his sax is really something remarkable to hear, though be aware, there’s some occasional panning of the sax in order to emphasize solo passages. Milton Banana’s drumming is subtle and at times almost inaudible on the original pressing, but takes on an entirely new dimension – literally – here. And although Getz is known as a father of “cool” jazz, wait until you hear him blaze on “So Danco Samba.”

I’ve always considered Astrud Gilberto to have the voice of an angel, and what a wonder it is to hear her sound so up close and personal and real. All I can say is, this Impex release it utterly stunning. You can picture her walking down the beach or contemplating quiet nights of quiet stars as she sings, sweet and sultry yet innocent, full of romance. Just beautiful.

I spoke with producer Abey Fonn and Nick Getz, Stan Getz’s son, about the making of the reissue and to talk about some Stan Getz history.

Frank Doris: This reissue is mind blowing, far better than anything else I’ve heard. Although it’s impossible to hear every reissue – I went on Discogs and there are literally hundreds of LP versions of Getz/Gilberto out there.

Abey Fonn: For me, it’s [about] redefining the definitive version. We always have multiple copies [of an album] to use as our benchmarks. I know that Analogue Productions put out a beautiful version. So, when we started this, we had a vision, and being able to work with the Getz family was just the icing on the cake. It put the whole project together in a way that I don’t think anybody else has done. We spend quite a bit of time on the mastering, so I’m very glad to hear you enjoy it.

FD: Nick, can you tell us something about yourself and how you got involved with this project?

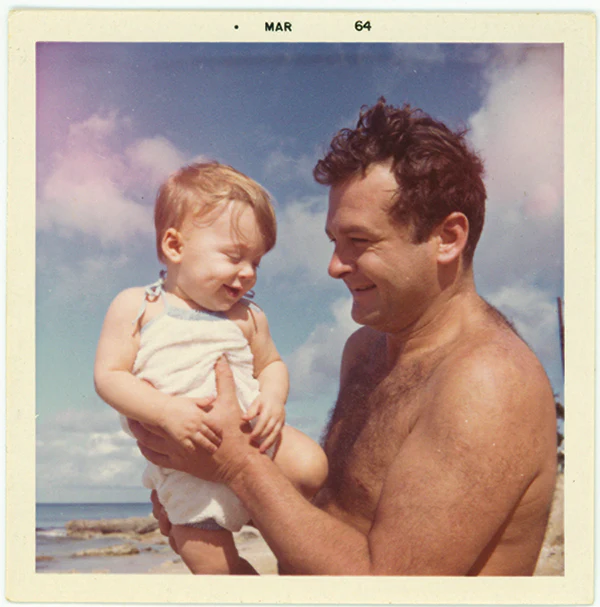

Nick Getz: Well, I’m Stan’s youngest child. He had five children – actually six. One was in the middle of all of us, out of wedlock. And I’m the only one who didn’t follow in his footsteps in the music business, either as a musician or somehow involved as a manager or booking agent or whatever. And he did that on purpose. I actually had an interest in piano and guitar, and he discouraged me from doing that because he saw how difficult it was for [his] children to live up to his name and success. And he loved healthy living. He was a very paradoxical guy. He loved cold ocean plunges and tennis and vitamins and health. So he tried to counterbalance the jazz musician lifestyle, the late hours and the smoky nightclubs. And he became very good friends with (Wimbledon tennis champions) Rod Laver and Lew Hoad.

He had me taking lessons with Lew when I was seven years old, and I took to the game and that became my career. He was very proud that I made a name for myself, became a professional player, and then had one of the most prestigious tennis director positions in the country here in Los Angeles at Hillcrest Country Club, which in the tennis industry is one of the best-paying and most prestigious jobs. I was there for 16 years until I retired in 2011.

My dad passed when I was 29 years old, and I didn’t get enough of him. I was always traveling and playing tennis tournaments and not at home. And he was on tour. So I’ve used the last 14 years to learn about him more and get to know him better. I’m doing a documentary film on him, and have a biopic film concept that is garnering some interest. In 2018 Jason Lord, a mutual friend, put Abey and us together and I got my mother involved to help as well.

FD: Abey, how was Getz/Gilberto produced?

AF: When Nick and I first connected, I said to him, there are so many versions of this album done globally, and gave Nick the rundown about what the reissue business involves and the costs behind it. And I said, “[reissuing Getz/Gilberto] is really not worth doing unless we do something exceptional and we are backed by the family.” And Nick was like, “you know what? This is what I want to do. I think you’re the right person.” Nick got his mom involved and connected me with the rest of the estate.

FD: How’d you get the master tapes, and what kind of shape were they in?

AF: Our QC director, Bob Donnelly, was heavily involved in the mastering process. The tapes came from Universal. We were really hoping for the original three-track[master] if that was still available. But the tape we got was the next best thing. It was what I call the “new master,” the master they made after the second pressing of the [original] LP. The tape was in relatively acceptable condition. It’s worn, it wasn’t shedding or falling apart, [but] it required some baking and some love from (mastering engineer) Bernie [Grundman] and it sounded good.

FD: Nick, you’ve talked about how Stan Getz didn’t like to rehearse.

NG: That was what he was famous for. He always made his fellow musicians very nervous because he didn’t like to rehearse very much, and he didn’t practice at home other than just hitting notes on the saxophone. He would pick up the sax and [just] hit notes. And we’d go, “what are you doing?” And he would say, “I just need to hit the notes clean, and if I’m hitting it clean, I can put it all together.” He believed in visualization much more than actual practice.

He would play ping pong [instead of rehearsing with the band], then sit and have a cigarette, take a break between games and listen to the band. And he would sort of nod and play another game and leave them to it. It was quite unorthodox. He actually was very disliked by a lot of fellow musicians because they felt he was very unprofessional by doing that. And I think more importantly, I think they were jealous of him that he was able to do that.

John Coltrane was the polar opposite. He practiced 10, 12 hours a day until his fingers would start to bleed and he would have to tape them up.

FD: This leads into another question. So many performers say that after a few takes, you’ll lose the spontaneity and the magic.

NG: Exactly.

Stan would tell people, “you better have your A game. I’m going home after two or three takes.” He thought it became stale [after that]. I think there’s something to be said for that. Sometimes you can just overdo it.

The first bossa nova album [Stan did] was called Jazz Samba. His friend (guitarist) Charlie Byrd asked him to make the album with him. My dad said, “look, I’ve got nothing going on at the moment. I’ll do it, but I’ll only come down for one day. I’ll fly down to where you are in Washington DC from New York, and I want to sleep in my own bed that night.” So he went for the day and they recorded in a church, the acoustics were good, and they made that album in one day. So yes, he could be quite impatient with long recording sessions. And that album swept the Grammys in the jazz category. That was the inspiration for the record label, Verve, to commission the Getz/Gilberto album.

FD: And then the record execs didn’t want to release the album because they thought bossa nova had become old hat.

NG: It’s a credit to my mother [Monica Getz] because they completed the album and…

FD: Did everyone involved think Getz/Gilberto was going to become a hit?

NG: I called my mother about it, because she was there. She said they thought they had done something good, but they didn’t know it would transcend the jazz genre into this internationally-appealing music that would win Album of the Year in the pop category over the Beatles.

But the ironic thing about “The Girl From Ipanema” was my dad didn’t want it released at all on the album. He said, “Astrid is not a professional, and she’s singing out of tune.” They all generally thought they had made a great album that could be a hit, but not “The Girl From Ipanema,” which is the biggest hit on the album! João [Gilberto] was of the same mindset. His wife had always tried to get [Astrud] in the band, like Lucy did with Ricky Ricardo. (laughs) And he was like, “oh, she sucks, and I can’t believe she’s trying to do this again.” He couldn’t quite wrap his head around it, but he [eventually] did.

FD: Unbelievable.

NG: The record gets completed, and then the stupid people who wanted my dad to perform with these top Brazilian bossa nova songwriters and musicians said, “oh, you know what? That was a fad. It’s over. Go make some rock and roll albums now, Stan.”

And so for 13 months, [Getz/Gilberto] was unreleased. An album that’s considered one of the greatest albums of all time. So my mom called somebody over at [trade magazine] Billboard. And this guy, his name was Bill Gavin, said, “listen, there are two ways to get the album out behind [the backs of] these record executives who said they didn’t want to release it. There’s payola, which means you pay off these DJs to play the music and make it popular.” My mom said, “we’re not doing that.” When she married my dad, he wasn’t very good with business and had inherited a lot of debt. She asked, “what’s the other alternative?” [Gavin] said, “you go to the [song] pickers who work for the DJs, and you give them the album and you encourage them to play it. Go to the markets you think it’ll do well in.” So my mom homed in on going to these pickers, and they would play it, and one by one in each city it went to top of the charts.

Then my mom went to the president of MGM, which owned Verve, and he goes, “yeah, I heard this song on the way to work on the radio. Why isn’t it released again?” And my mom told him Verve people [wouldn’t release it], and [the president] said, “consider it released.” So, full credit to my mom. She knew the potential of this and wasn’t going to give up.

She was very, very shrewd in business and understood how to market. My dad, she cleaned him up, put him in a suit and a tie, and managed him behind the scenes. Men would come over [to the house and talk to Stan] and she would serve cookies and coffee to them, and listen in from the kitchen, and then tell my father, “that guy’s full of it, and we’re not doing it that way, and we’re going to do it this way!” They were a good team. But at that time, women really weren’t respected or allowed to be in the meetings with the men anyway, so she was a woman ahead of her time.

FD: It’s well-known that your father struggled with substance abuse, and she must have been a huge part of getting him back on track.

NG: She was able to keep him sober during that era with something called Antabuse, which is a pill that alcoholics are supposed to take on their own. That doesn’t really work because if you want to relapse, you don’t take a pill that’s going to make you have a violently ill reaction. So my mom would dissolve it in his food, and so would some of the musicians when she wasn’t on tour with them. My siblings [also] did it.

And so for many, many years, he thought he developed an allergic reaction to drinking. He was sober, I would say, from the mid-sixties to 1980. He would relapse once a year or something, and it would be a disaster. But [despite] his drug addictions and alcoholism, he was a good guy. He was really, really sweet, [but] it was a Jekyll and Hyde situation. The minute he touched alcohol, [even] his voice would change. I’ve been able to separate the man from the addiction and come to terms with it. My mom basically did everything she could, but [eventually] she couldn’t take it anymore.

FD: Let’s move on to a happier subject.

NG: Well, you asked about his influences [in a previous e-mail]. It’s really only one influence, only one. Lester Young. That’s who Stan modeled himself after, and that was his idol and nobody else.

FD: According to Wikipedia his big influence was Stan Kenton.

NG: He actually didn’t like Stan Kenton. He thought Stan Kenton was kind of a superficial guy. He liked Miles until Miles started getting into drugs. My dad rarely recorded on drugs or alcohol [except for] Focus, after his mom had just died, and he was drinking and it was impossible to be with him in the studio at that time. But he loved Miles. He loved Chet Baker too.

Towards the end of his life, he and Miles spoke once about it and said, “we thought we were playing so much better, but we weren’t, and we could have been even better.” Maybe a little bit of drugs or alcohol can loosen you up and make you a little more creative or something, but there’s a quick point of diminishing returns.

[Stan] loved the way Frank Sinatra sang. He loved melody, and he played with melody. He loved Charlie Parker. And he thought his drummer, Roy Haynes, was incredibly underrated. He thought Bill Evans was a great musician.

FD: I can’t say enough great things about Bill, and your father was on the same level. It’s that indefinable something.

NG: There’s been millions of musicians, but only one got the nickname, “The Sound.” And it’s just because he does have a sound. It’s very, very, very harmonic, beautiful sound.

FD: That’s another thing that really comes through on this reissue, the actual sound of his saxophone. It’s got so much presence and feeling. On some songs it’s like, “hey, you didn’t blow out the spit valve!” I can hear it rattling around; it has this kind of graininess and texture, but that’s part of it. Speaking of saxes, I can’t tell you how many sax players I’ve talked to who play a Selmer Mark VI. Why did Stan Getz like to play one?

NG: I didn’t know, so again, this is from my mother, but she didn’t know anything about a Mark VI or Mark VII or all that stuff. But she did know that there was a saxophone called Conn. [That’s what my dad originally played] and it was stolen from the trunk of his car, and he was crestfallen. He felt like he could never feel like he could duplicate quite the same sound as that saxophone.

And a police officer had never forgotten about it. About eight years later, I’d say this happened in the mid to early Fifties, and then in the early Sixties around ’62 when I was born, the policeman found it. He just went around on his free time trying to locate it, and he went to a pawn shop and found it. But my dad never used that saxophone again. He said there was something about it that didn’t feel the same. Now, I don’t know if he, in his mind, had built it up to be something better than it was, but he never used that again, that saxophone. Maybe it was damaged or something. He played the Selmer [after that].

When dad passed, [he left] three or four saxophones. One of them is in the Smithsonian. My sister is holding one that belongs to the estate. This out of wedlock child has another one. He’s a good musician in Sweden, and inherited some of [my dad’s] talent, I guess. Then I think one of them was under repair, and the guy who repairs my dad’s saxophones still has it and is like 96 years old. And he would give it back if we asked for it.

FD: This Impex reissue sounds much, much better than my original Verve pressing, although the original sounds really good.

AF: We had a couple of [vinyl] versions as our benchmark and part of our process is listening to what’s out there, and discussing what we like about it, what we don’t like about it, and speculating on what was done to it. With our definitive release, we wanted to make sure it was as close to the tape as possible. But there was a lot of EQ required, and I think Bernie did a really great job with creating the separation of the instruments. There is something magical about this release, in my opinion, because it feels so musical. There are releases that are technical, they’re very clean, and some of them are very precise. There are different ways of every label viewing what they want to achieve.

We went through so many test cuts to get what we wanted before we went to cutting the lacquers. And it was really Bob Donnelly who wanted to keep the tapes intact, which meant keeping the flaws intact. We were really worried that maybe some of the people who weren’t as familiar with the album would think some of the tape issues or the fluttering and stuff like that was [because they bought] a defective record. That’s why we decided to put a technical note [in with the album] to make sure that people understand these are not defects. These are actually part of the tape.

We will also be releasing this album on SACD and there it will be done using the Plangent Processes system. [This process corrects for wow and flutter to provide speed stabilization – Ed.] So we’re still using the tape, but there’s now a digital fingerprint and people will be able to listen and compare and see what they like. Hopefully we’ll have that by late spring or early summer. We decided to keep two very separate versions and have the analog to stay truly analog.

NG: The vinyl will be limited so tell your readers not to regret having ordered theirs before it sells out.

Thank you so much!

******

Getz/Gilberto

Impex Records 1STEP IMP6041-1

Produced by Abey Fonn

Executive producer: Robert Bantz

Associate producer: Bob Donnelly

Mastered by Bernie Grundman at Bernie Grundman Mastering

Liner notes and historian: Charles L. Granata

1STEP pressing by Record Technology, Inc.

Plant manager: Rick Hashimoto

180-gram LP plating and quality control: Dorin Sauerbier and Bryce Wilson

1STEP package produced by Stoughton Printing

This article previously appeared in issue 205 of Copper Magazine.

Leave a Reply