Read the first part of our interview with Chad Kassem here.

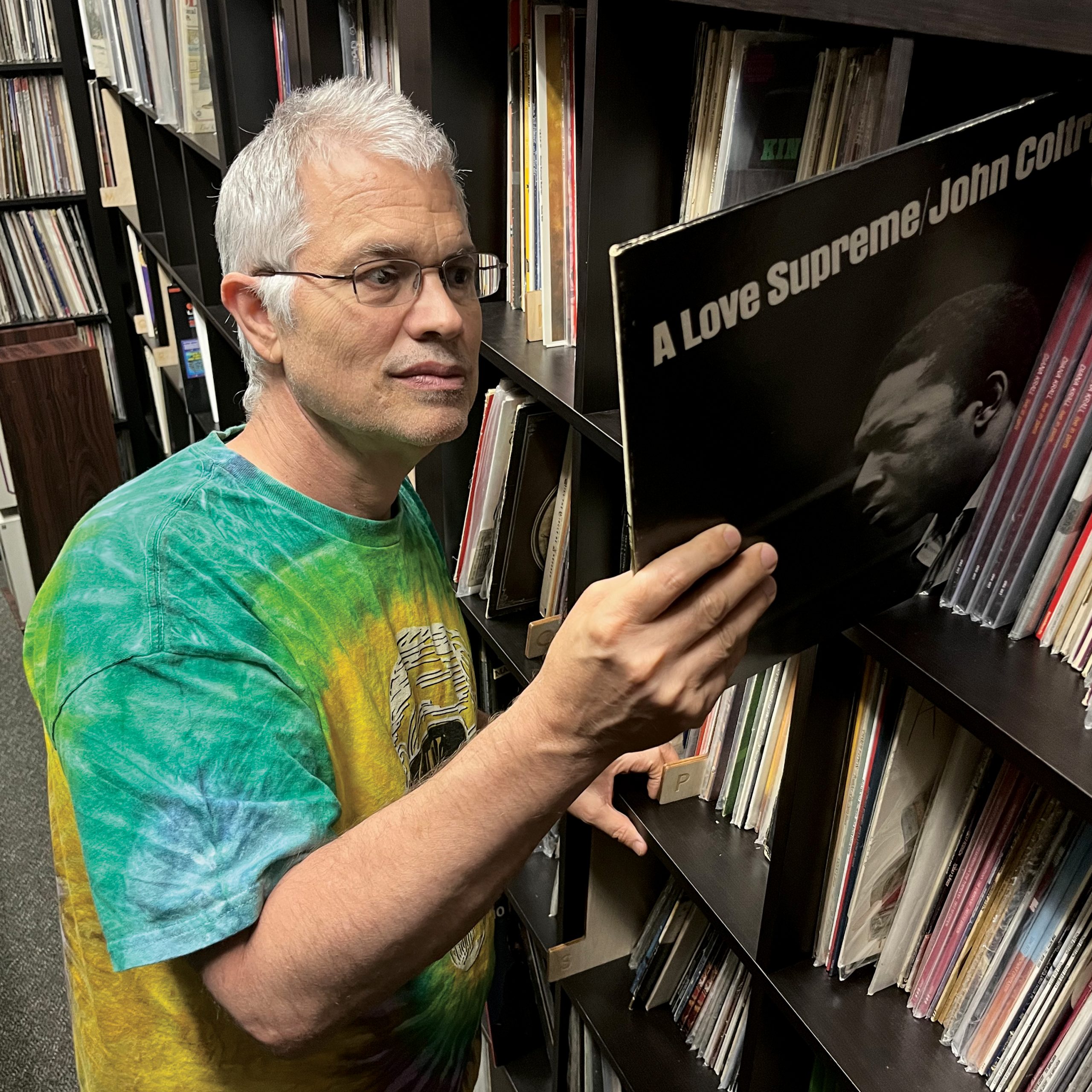

In 1984, at age 22, Chad Kassem moved to Salina, Kansas, where he worked as a cook. He also became obsessed with records.

“Every waking moment, I would just think about records and finding them,” he said. “By ‘86, I started Acoustic Sounds out of my apartment. You couldn’t even move. The whole place was full of records. We had boxes of records in the bathroom!

“So, I’m like, okay, it’s time to move. I bought a house in a suburban neighbourhood. I had five to ten employees working out of my bedrooms, with their cars parked in front of my house. When the 18-wheelers started coming, dropping off pallets, the neighbours started to complain. I needed to move again. In ‘91, I moved into a normal business space. In around 1990, I released my first reissue, and then in ‘94 is when I recorded my first blues record—by Jimmy Rogers. So, if you look back at someone who worked for a bit more than minimum wage, who used his money to buy a home, release his first album, then record his own record on his own label—we did a lot in a short time.”

What was his first reissue?

“Jules Massenet’s opera Le Cid with Louis Frémaux. I did it through the guy who had the license from EMI. I knew him, but I didn’t know the big dogs at EMI. I approached him, and he said, ‘I can’t relicense something that was licensed to me. But I can make you the quantity that you want and I’ll make it how you want.’ I said: ‘I want you to use Doug Sax and do it at the RTI pressing plant.’ He gave me a finished goods price with the jackets and I took it. That was my first reissue, probably in ’89, ’90. It didn’t have an Analogue Productions catalogue number—it wasn’t on Analogue Productions—but that thing sold like crazy because it’s just a showstopper. The dynamics are unbelievable.”

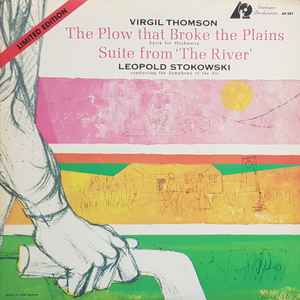

“My first Analogue Productions release was in 1991—Virgil Thomson, The Plow That Broke the Plains. It’s Classical music. That’s how it started. Everything after was a natural step forward, a progression, me getting closer to controlling the quality and putting out the music I wanted.”

Soon after came those big jazz titles from Blue Note and Fantasy.

“That started in about 2002,” said Chad. “It was a lot of work. Very satisfying. Those records are killer records. Whoever owns them has got some great-sounding records.”

I asked Chad how he managed to get those titles.

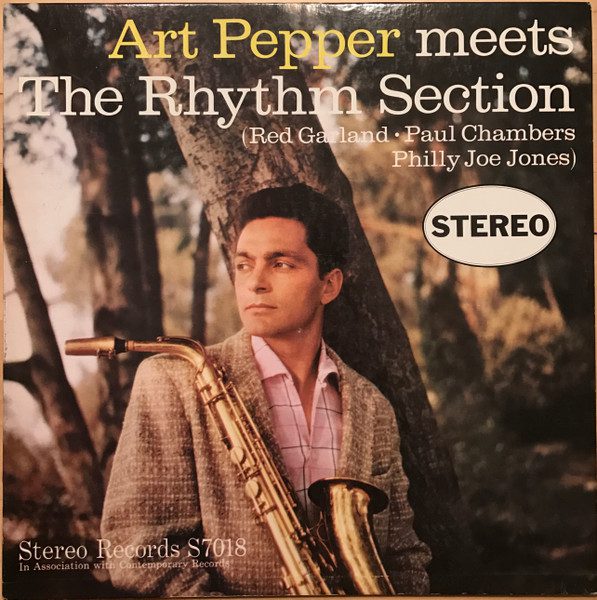

“In 1992, I called Ralph Kaffel, president of Fantasy Records. Fantasy owns Fantasy, Contemporary, Pablo, Prestige, Riverside. I told him I wanted to reissue Sonny Rollins’s Way Out West and Bill Evans’s Waltz for Debbie. Those were my first two, released in 1992. Over time, Ralph and me built a good relationship and it’s still going today. Now, I’m helping Fantasy with the Acoustic Sounds Contemporary Series, and then we’re doing 50 Prestige titles on our own label.”

When did he buy his first record press?

“Around 2009-2010,” he said. When I replied that he must’ve had a tough start considering the state of pressing plants in general at the time, Chad took a deep breath, and I could see in his eyes the pain seeping in from his memories.

“It took lots of work, man,” he finally said. “Lots of damn work. Not easy. Hardest thing I’ve ever done, even if I didn’t do the work—it’s a team of people. I just paid for it all. But it’s hard. People don’t know how hard. They’re just asking when the next record is coming. They don’t know. And I don’t know why all these people want to open pressing plants. They don’t know what they’re going to find out. You could talk to them till you’re blue in the face on how hard it is. I mean, they believe it’s hard, but they’ll never believe how hard for how little profit.”

I asked Chad about the prospect of replacing the skilled individuals on his team. Given the specialized nature of the technology, was he concerned about finding capable successors as his workforce ages?

“There are a lot of issues, and that certainly is a big one,” he said. “We’re training, but people quit. When I said it’s hard, you can put that in with the hard.

“It really started with COVID,” he continued. “Before that, things were going smooth in the world. Every store knew how many things to order—cups or phones or whatever it was. It was like 30 years of practice in ordering, getting what you needed. Then all hell broke loose. It’s still not back to the way it was and people don’t want to work anymore. That said, I have a great crew. We pretty much have all the jobs filled. It’s just so much more difficult now. COVID caused me problems, caused everybody problems, caused a lot of death. But it also doubled my business overnight.

“Nobody really knew how to handle the COVID situation,” he said. “A bad thing about it was some states didn’t shut down. Our competitors in those states stayed open. It was an unfair situation. Our state made a shut down. We had to shut the pressing plant down. It was a nutty time, but we were able to keep going. At the same time the government is shutting you down, business is rising. We haven’t quite caught up, but we’re getting closer.”

One of Chad’s companies is Quality Record Pressings, the plant where he presses his records. How many records are pressed there annually? “About a million and a half,” he said. “We’re running 24 hours, and we were doing that with two shifts. Now we have three shifts, so hopefully we’ll make more.”

Ultra High Quality Record (UHQR™) vinyl is the high-end product of Analog Productions, the ‘audiophile’ division of Acoustic Sounds. UHQR records are made with Clarity Vinyl, originally introduced by JVC Japan in the 1980s. I asked Chad to tell me more about it. “Clarity Vinyl is vinyl in its natural state,” he said. “It comes out that clear. The black is a carbon dye additive just to make the colour. Now what you get from the colour is you can see the grooves better. Before vinyl, there was shellac, and it came from a bug called the shellac beetle. They squeezed the insect to make the resin. That’s where the black colour came from. When the industry went to vinyl, it added carbon dye to get the same colour. It’s like putting an additive in your food. With UHQR vinyl, we keep it natural. We don’t add the additive. The vinyl is pure. That’s the first thing. The other thing is we use ‘flat profile’ 200-gram vinyl.” A record that undergoes the flat-profile process comes out flatter than a typical record. This allows the needle to track the groove better.

“Our goal is to constantly improve,” he said. “Whenever someone buys a record from me, I’m reinvesting money into trying to make our product better, trying to upgrade our machines, trying to license more product.”

I had heard that Acoustic Sounds had recently acquired its own printing facilities. I asked Chad if they were printing their own record jackets.

“No, we do everything from the microphone to the mastering, to the plating, to the pressing, to the sleeving, to the distribution at retail and wholesale. The only thing we don’t do is the jacket. I did buy a printing company that prints the labels, the inserts, all kinds of things. And we could print the jacket, but I decided at some point I got to go to bed at night.”

Chad does a lot of business with RTI, another label that presses its own high-quality records. Aren’t they competitors?

“We don’t consider ourselves competitors,” Chad said. “They help us, and we need more records made than we can make ourselves for our own label. Their quality is high. Don, the owner, is a friend, and I’ve been pressing with him since the ’90s or so. He helps us. We are better together. We’re stronger together. He’s so busy and I’m so busy. We’re not fighting. I send him so much work.”

Was that part of his philosophy, to form alliances rather than adopt a more confrontational stance against competitors?

“I try to,” Chad said. “But not quite like Don. He helps a lot of other pressing plants. He wants this industry to grow and feels that he needs to share his knowledge, and sometimes I think the people he helps… well, I don’t think if the shoe was on the other foot they would help him. I look at him as kind of, in the record pressing area, my mentor. We were partners at AcousTech Mastering inside of RTI, working with (mastering engineers) Stan Ricker and Kevin Gray.”

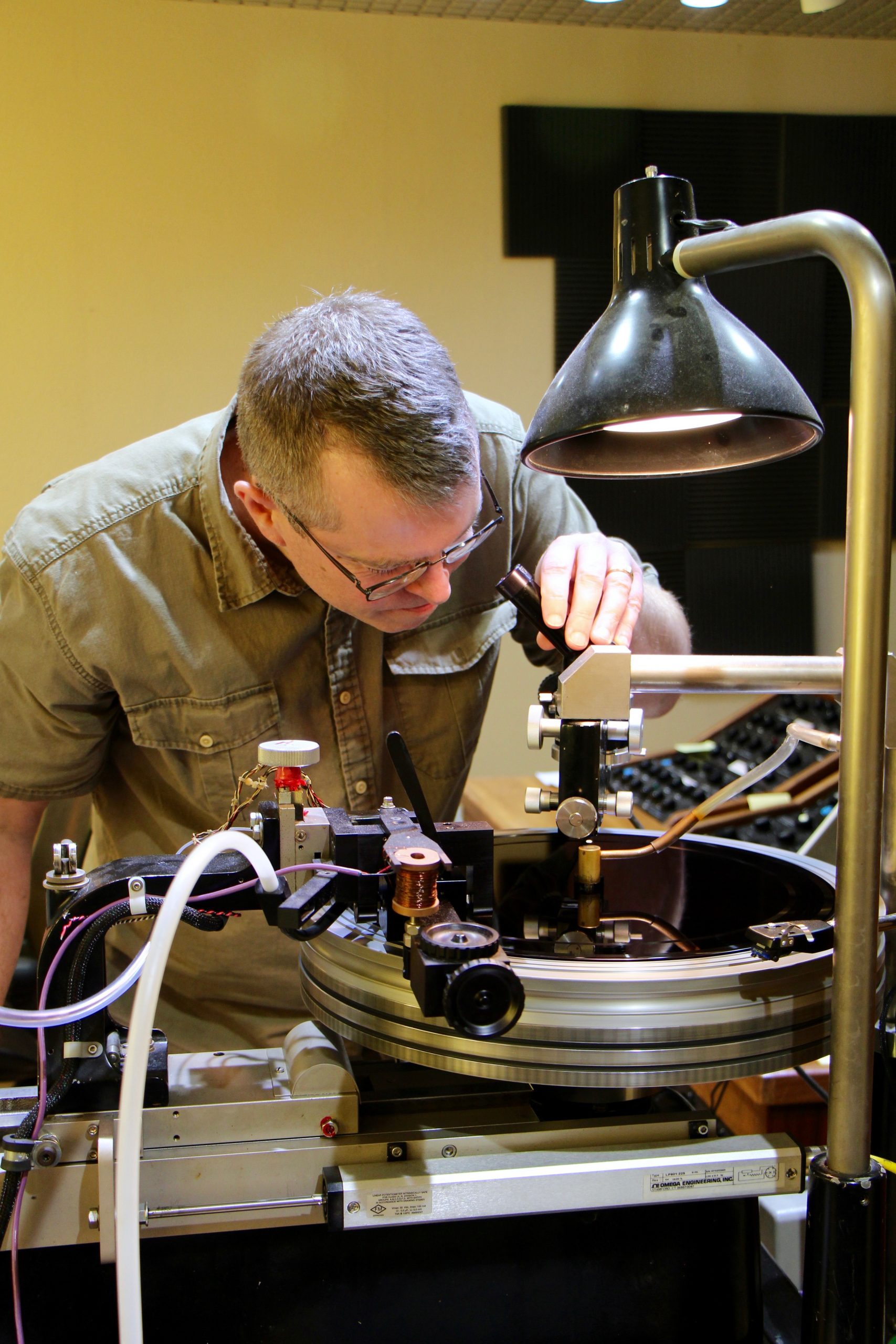

After Chad purchased The Mastering Lab in 2015 from the estate of legendary mastering engineer Doug Sax, he relocated it from Ojai, California, to Acoustics Sounds’ headquarters in Salina, Kansas. I asked if all the mastering was now conducted in-house.

“We’re starting to do more,” he said. “I’ve got a mastering engineer working for me—Matt Lutthans. But we still use Bernie Grundman, Ryan K. Smith, Kevin Gray. We choose different people for different occasions. But they’re all the top. If I go to one over the other, it’s because I think they may have an edge for that project. I’m always thinking about making the highest quality. I don’t just use one mastering engineer. I did when Doug Sax was living. I used him for my first 40 records.”

Leave a Reply