It all started with…

…the Beat. That rhythm inside us that keeps us alive, that reminds us… We Are Alive! It races when we’re excited to meet someone new. Its pounding pulse is primal. And it’s the backbone behind all forms of dance music, and the primary ingredient that defines disco. But disco didn’t magically materialize out of thin air, on a feverish Saturday Night at New York City’s Studio 54. There were dancers gracing dance floors well before John Travolta shook his booty in his famous white suit. To better understand how we got there and beyond that, we must go back in time, to the beginning of the Beat.

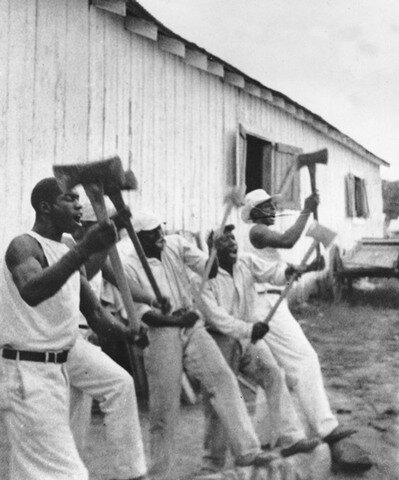

In Ancient Rome, galley rowing relied on a steady meter to propel a ship across the sea. Fast forward to the mid-17th century, when captured Africans stolen from their homes and sold into slavery to colonial America — soon to become the United States — started to incorporate work songs in their routines. These slave songs, or “sorrow songs” as they were known, served several purposes: to establish a rhythmic workflow in the cotton plantation fields of the south to improve production, and to offer hope when there seemed to be none; through song, slaves could pass on subversive messages, better cope with their daily trials and tribulations, and reconnect spiritually with their African homeland.

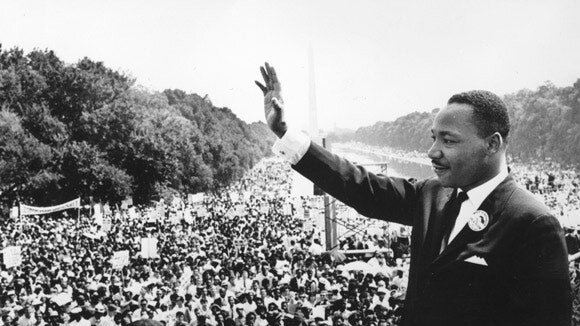

The African tradition of song could manifest itself in a call-and-response pattern. Going back centuries, the call and response was already widespread in African culture, encompassing many customs and practices before taking root in the segregated fields of southern states. It’s part of the fabric of future branches of African American music genres emerging between the 17th and 19th century — such as spirituals, gospel, and blues, along with their many derivatives. This traditional means of expression, be it in the form of field hollers between slaves, or religious proclamations between pulpit and pews, continued to the end of the civil rights movement with classic tracks such as “Respect” and “Say It Loud – I’m Black and I’m Proud”.

The call-and-response practice found favor also in the chain gang prisoner work songs, and exists to this day in U.S. military training songs. While 17th to 19th century European classical music championed string ensembles, complex orchestral development, dynamic expressions, and vast tempo variations, African American music instead prioritized percussive, rhythmic, and groove-based aspects. At times, musical improvisation appeared, eventually finding its way at the heart of jazz in the early-1900s.

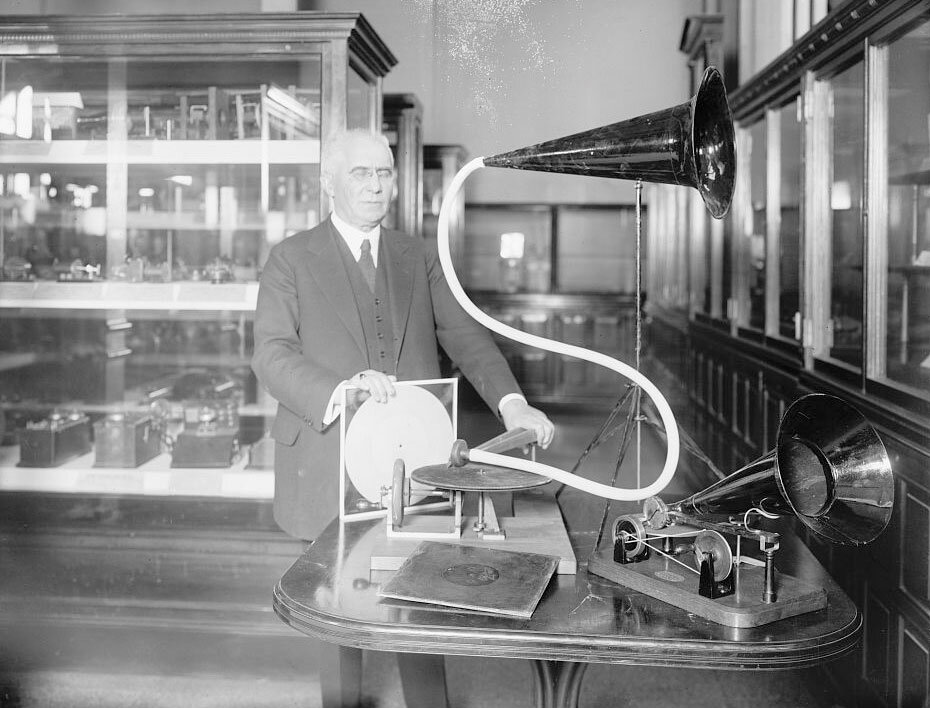

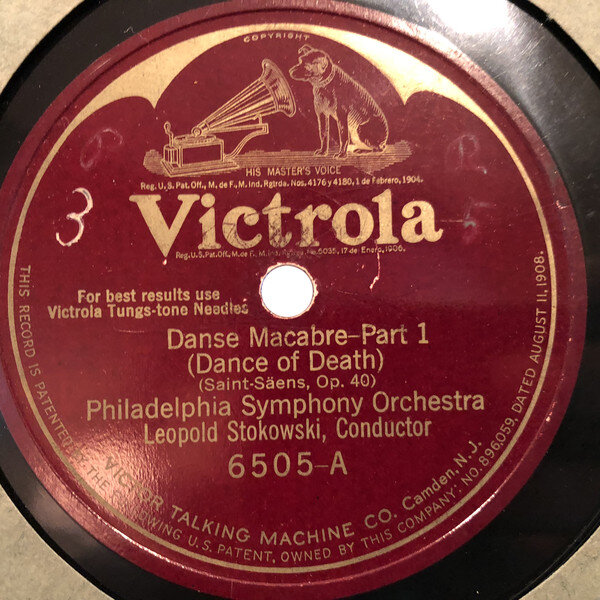

Although Edison invented his phonograph in 1877 and opened the door to primitive acoustic recordings — first on tinfoil and later on wax cylinders — it wasn’t until a decade later that Berliner perfected his flat-disc gramophone, eventually allowing easier duplication and mass production of shellac records near the turn of the century. Berliner moved to Saint-Henry in Montreal, Canada, where, in 1909, he registered his company name as the Berliner Gramophone Co. The most popular format was the 10-inch 78 rpm.

Because of its high-speed rotation and relatively ‘wide-track’ groove space, most recordings’ playing time averaged around the 3 minute mark, with 12-inch 78s running at most 4 to 5 minutes, which meant that both 10” and 12” formats limited performances to a single song per side. In that sense, the latter can be considered the first ancestor of the DJ maxi-single introduced in the 1970s. In fact, the gramophone’s invention benefited disco more than any other musical genre. How so? Because, at their root, genres such as classical, blues, and jazz, are meant to be performed in a live context, and would have surely survived independent of the record, whereas with disco, it’s the exact opposite. Because of its studio-driven construction, disco is best served on record on a good audio system rather than live, and would never have seen the light of day without it. Think about it: You never hear anybody boast that they have tickets to an El Coco concert! But on record, well… welcome to ‘paradise’.

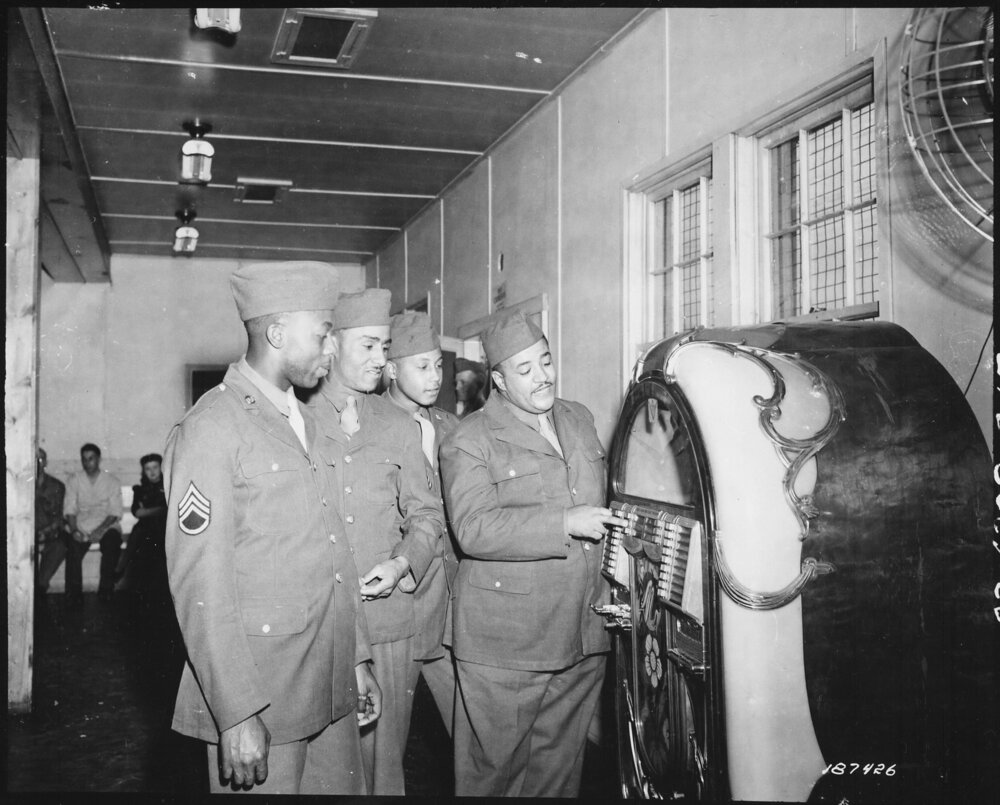

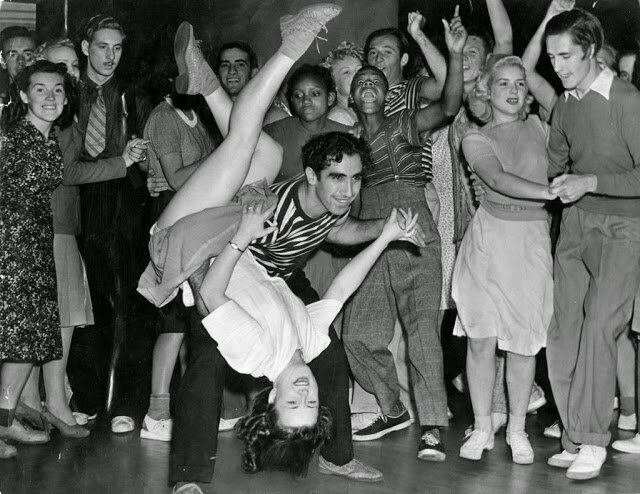

By the mid-1920s, as electrical recordings replaced acoustic ones with improved bandwidth and fidelity, the first song-selectable, coin-operated jukeboxes were filling juke joints as African Americans jitterbugged to their favorite songs at the drop of a dime, with no need of a live band, and at the time of their choosing. It was the audio equivalent of our Netflix streaming service.

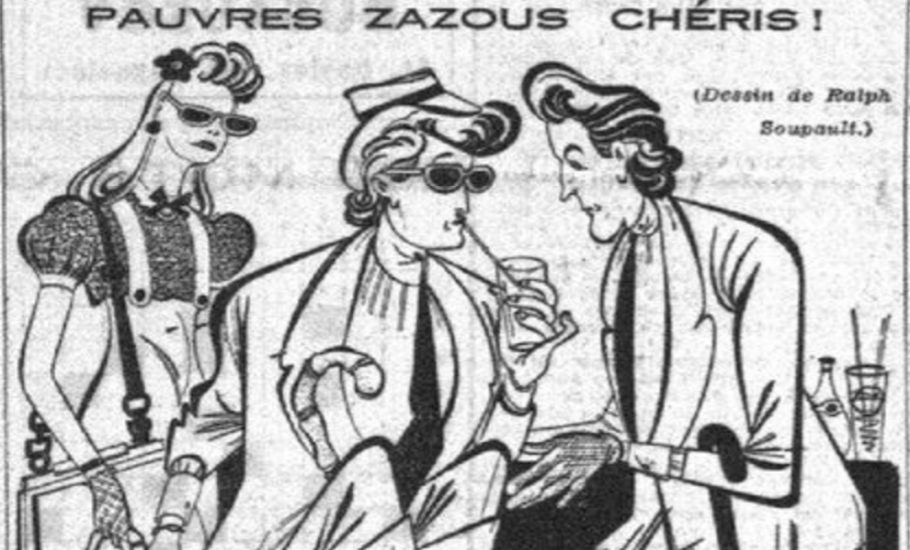

In the early 1940s, as the big band era was in full swing, Hitler’s Third Reich worried that the West was winning, and corrupting, the hearts and minds of their youth via American jazz records and the Western Way of Life. Swingjugend (Swing Kids) in Germany and Zazous in Nazi-occupied France formed a counter culture, clandestinely meeting up in bistros and basements, sometimes aligned with members of La Résistance. Soon, swing clubs and places like La Discothèque, reportedly situated on rue de la Huchette in the Quartier latin and equipped with a jukebox or a single turntable plus some swing records, served as a makeshift club where patrons partied away. It was a temporary refuge from reality, and a rudimentary rave literally underground, undertaken five decades before raves were even a thing. As the Allied forces put an end in 1945 to the European theatre that was World War II, Major Jack Mullin of the U.S. Army Signal Corps, on assignment in Frankfurt, Germany, brought back to America two Magnetophon reel-to-reel tape recorders, and with financial help and the backing of singer Bing Crosby, convinced Ampex to manufacture the first American mono magnetic tape recorder, the ‘Model 200’, in 1947.

Improvements in the field of recording followed in the early 1950s with the advent of multitrack recording, a technique directly inspired by inventor and guitarist Les Paul’s Sound on Sound experimentations. This added flexibility was essential in the development of disco, which was multilayer-crafted from the mixing board as opposed to how classical, blues, and most jazz records were being made, with musicians playing together in ‘live in-studio’ or ‘live in concert’ session takes.

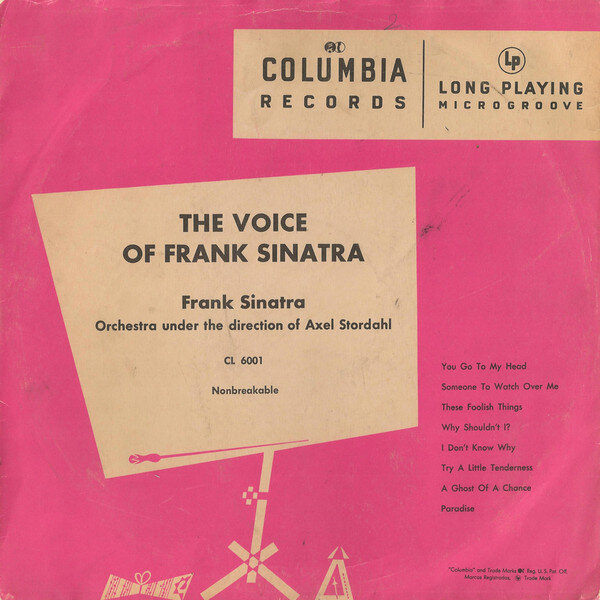

In 1948 came the 10-inch and 12-inch microgroove LP (Long-Playing) record formats by Columbia Records, each allowing, at over 20 minutes per side depending on cutting level and bass content, for a much longer playing time over the older 78s. This also allowed disco — and of course all musical genres — to have a much larger creative canvas on which the music could play out over the competing 3-minute single.

In the next chapter: examining disco’s close relatives. So Get Ready, so Get Ready!

Leave a Reply