“I got somethin’ that makes me wanna shouta,

I got somethin’ that tells me what it’s all about,

I got soul and I’m super bad …”

—James Brown, “Super Bad”

Blues migrated towards the urban centres, along its way electrifying guitars and gigs, as black musicians fleeing southern racial segregation strived for more economic opportunities and a better life in places like Detroit, Chicago, and New York City.

Blending the music styles of blues, boogie-woogie, and swing begat jump blues in the 1940s. In 1948, Billboard magazine’s music journalist, Jerry Wexler, coined the term rhythm & blues as a replacement for “race music” or “race records”, terms of segregation for a segregated society often used by artist and record company alike. A few years later, Wexler would play a significant role as record producer for Atlantic Records, one of the first and most influential labels in R&B and rock music history.

The stylistic differences between jump blues, R&B, and rock & roll were small, more semantic than clear-cut, as the latter genre was largely first promoted by radio disk jockey, Alan Freed, as a means of getting White teens to embrace Black music in a ‘nonthreatening’ way.

“Do you like that music

That sweet soul music…”

—Arthur Conley, “Sweet Soul Music”

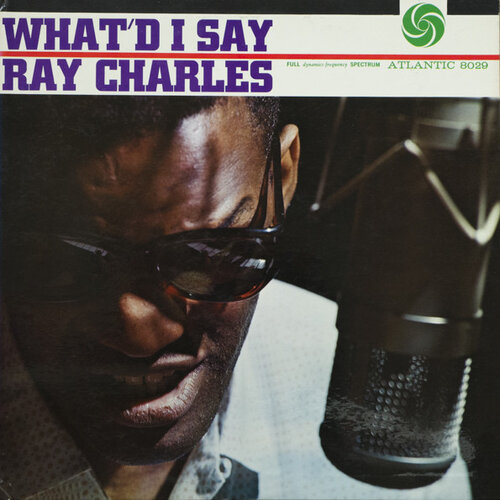

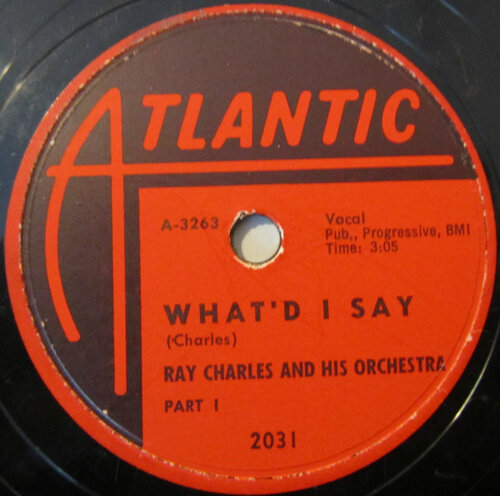

Combining gospel with rhythm & blues, soul music mixed the sacred with the secular beginning in June, 1959, with 28-year-old Ray Charles’ iconic R&B-soul hybrid hit “What’d I Say” [Atlantic 8029] perfectly capitalizing on a call and response between him, his Raelettes’ backing vocals, and his orchestra’s horn section. This ménage à trois part of the song created quite a stir at the time, resulting in the song being banned by many White and Black radio stations for its overt sexuality.

HITSVILLE U.S.A.

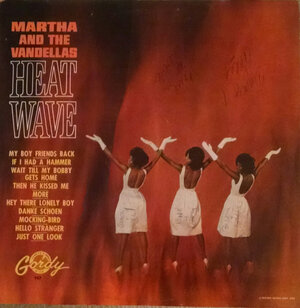

“It’s like a heat wave…”

—Martha and the Vandellas, “Heat Wave”

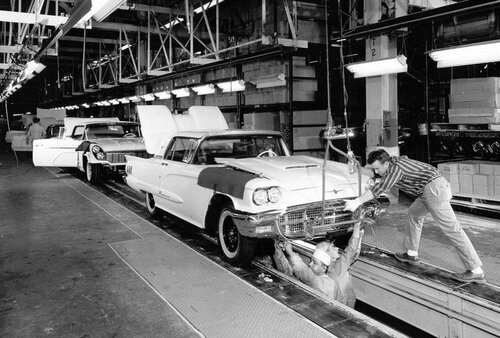

On January 12, 1959, five months prior to the release of Ray Charles’ “What’d I Say”, Motown Records was founded in Detroit, a.k.a “Motor City” for being the backbone of America’s thriving blue-collar industrial workforce thanks to the Big Three—Ford, GM, and Chrysler.

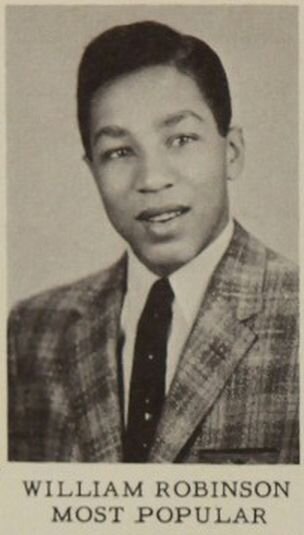

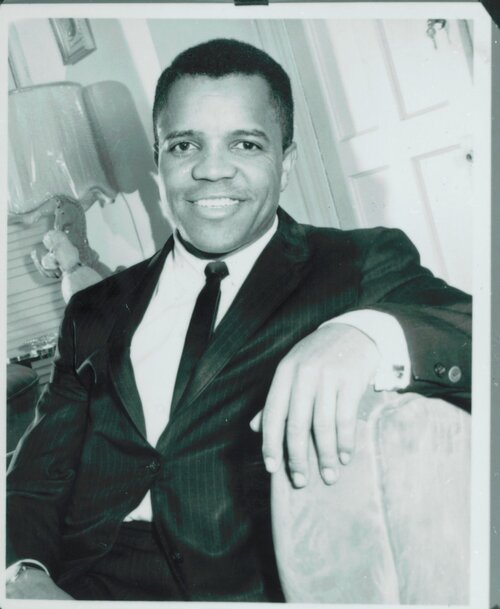

After meeting 17-year-old singer, Smokey Robinson, in 1957, Berry Gordy Jr. borrowed 800 bucks from family, and soon created the most successful record label owned by an African-American.

Hired briefly as an auto assembly worker for Ford-Lincoln-Mercury, Gordy Jr. applied the car company’s manufacturing model to his music business enterprise, designed to not only establish the sound of Black America but of White America as well, or rather “The Sound of Young America”, as per the company’s slogan.

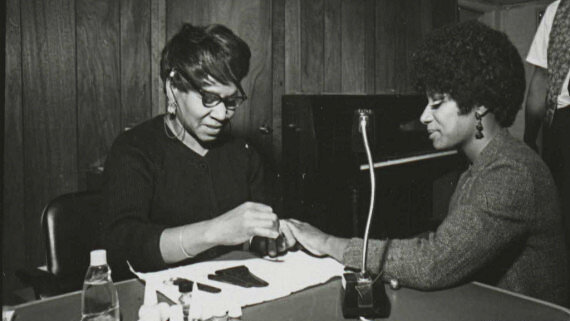

Gordy Jr.’s hit-making approach—Motown would dominate the charts from 1963 to 1972—was multipronged. A&R (Artists & Repertoire) scouts were used to recruit a large pool of young, fresh, eager Black singers, whom charm and artist development manager, Maxine Powell, would figuratively and literally groom, coach, and dress, while choreographer, Cholly Atkins, developed the trademark Motown moves. Both shaped the public personas of their charges to project a polished ‘clean class’ image to the mostly White audience.

The composing, arranging, and producing team of Lamont Dozier and brothers Brian and Eddie Holland, a.k.a. as Holland-Dozier-Holland or H-D-H, kept the round-the-clock supply of hits going for Motown until the trio’s departure in 1967.

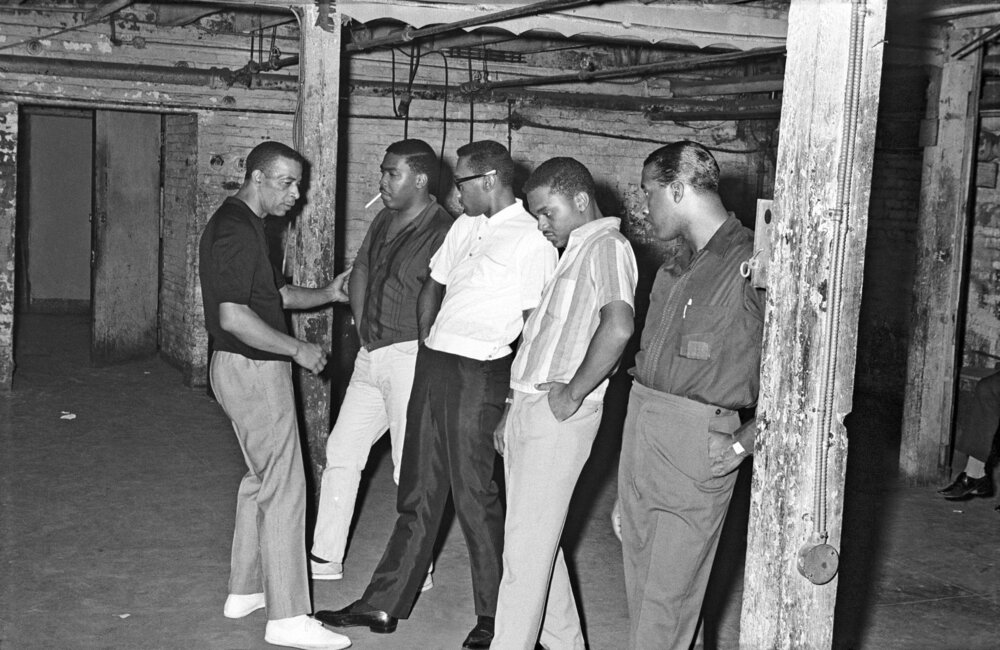

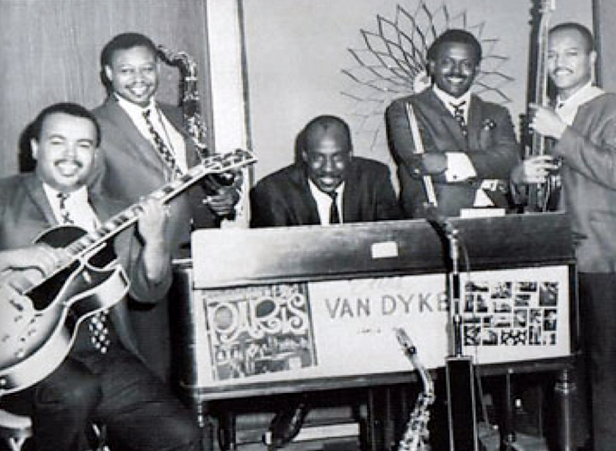

H-D-H, along with other music writers, were backed musically and instrumentally by The Funk Brothers. These non-credited Detroit session musicians—which included, among others, keyboardist Earl Van Dyke and bassist James Jamerson— formed the backbeat of Motown’s house band and were instrumental in forging the famous Motown Sound.

Recordings were made at “Hitsville U.S.A.”, Motown’s headquarters, the two-story house situated at 2648 West Grand Boulevard that served as recording studio and administrative office on the ground floor, and Berry’s living quarters and A&R division on the second floor. It’s now the Motown Museum.

In tandem with Motown Records were label offshoots Tamla and Gordy, with no apparent artistic differences between them.

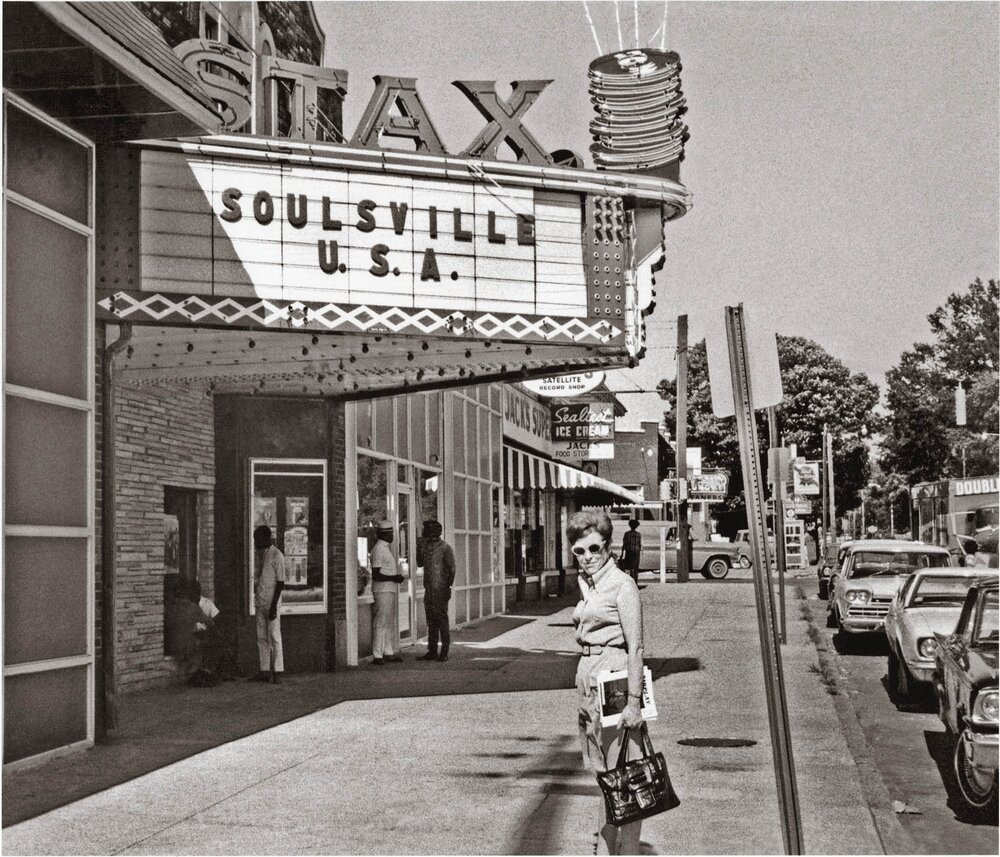

SOULSVILLE, U.S.A.

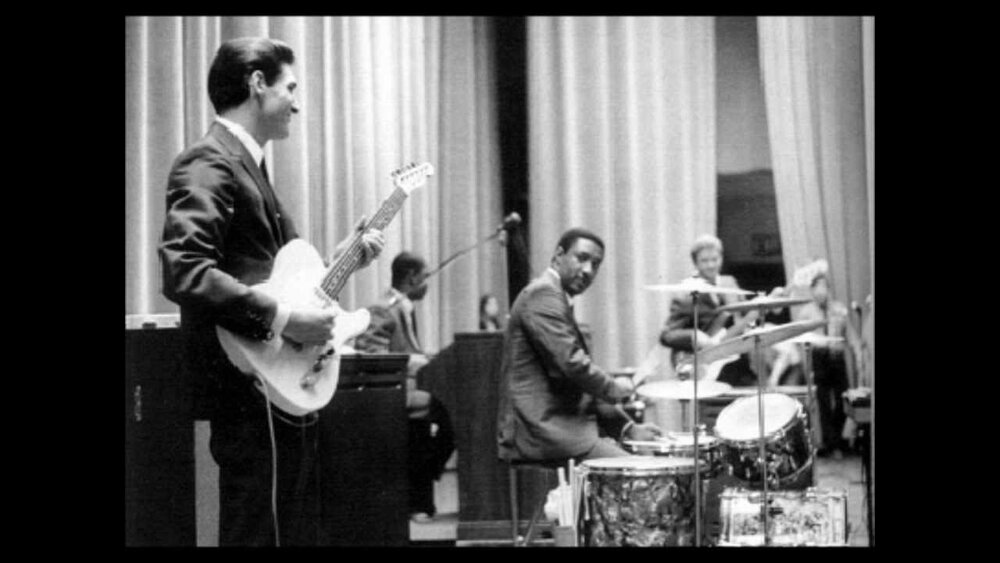

In an alternate universe from Detroit Michigan’s Motown was Memphis Tennessee’s Stax Records, the latter a portmanteau for Jim Stewart and his sister Estelle Axton. Stax was founded in 1961 after converting country music-oriented Satellite Records just four years into its infancy. Whereas Berry kept a tight rein on every aspect of the recording process, focusing on achieving a light, uplifting, bright pop-soul sound, Stax and its subsidiary Volt label dished out dirtier organic southern soul food relying on roots and rhythm & blues as the recipe’s main ingredients. They were well catered by their own soul kitchen cooks—no wonder their first hit, released in September, 1962, was called “Green Onions” [Stax 701]—and house band Booker T. & the M.G.’s, comprising Booker T. Jones on organ and piano, Steve Cropper on guitar, Al Jackson Jr. on drums, and Lewie Steinberg on bass, later replaced by Donald “Duck” Dunn in 1965. The group was racially integrated, a real rarity at that time.

Despite releasing several albums under their own name along the way, Booker T. & the M.G.’s are best remembered for their behind the scenes work, laying the foundation for soul giants Rufus Thomas and daughter Carla, Otis Redding, and Wilson Pickett, to name a few, thus helping to create what would be known as the Memphis Sound.

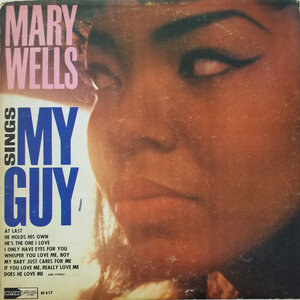

Back in Detroit, the team of H-D-H penned the song that would launch the “Motown Sound”, making waves with Martha and the Vandellas’ “Heat Wave” [Gordy GLP 907] in July 1963. The group would have a second big hit exactly one year later with “Dancing in the Street” [Gordy 7033], while singer Mary Wells would become a “one-hit wonder” with the single “My Guy” [Motown 1056] in March of ‘64.

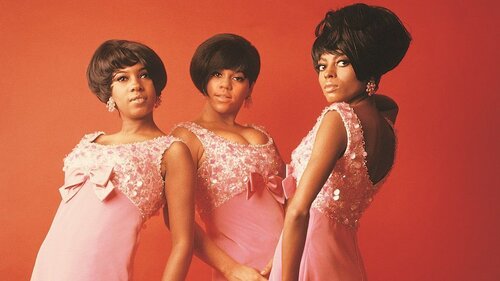

Come summer, the musical tide would rise several levels with the first of a string of number one hits—bringing the total to 12 throughout the decade—for Motown’s most successful act of all time, The Supremes.

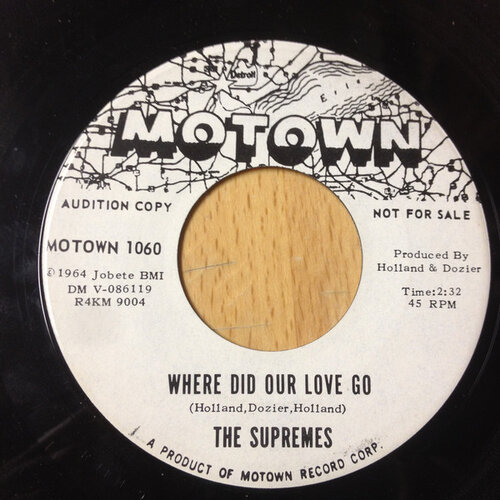

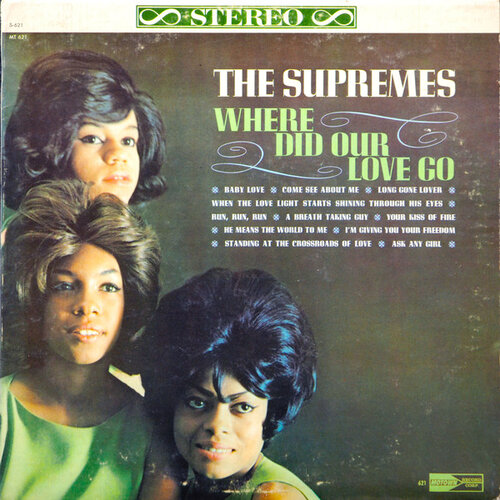

Led by singer Diana Ross, The Supremes—billed as Diana Ross & The Supremes starting in July 1967—also initially featured Mary Wilson and Florence Ballard. Due to her excessive drinking problem, Ballard was replaced by Cindy Birdsong in 1967. After a lackluster debut album—Meet The Supremes—in December, 1962, the trio hit their stride with “Where Did Our Love Go“, released in June, 1964, first as a single [Motown 1060], then, in August, as the title track to their second album [Motown S-621].

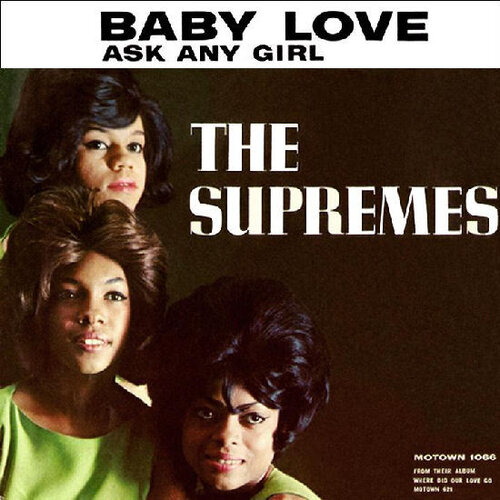

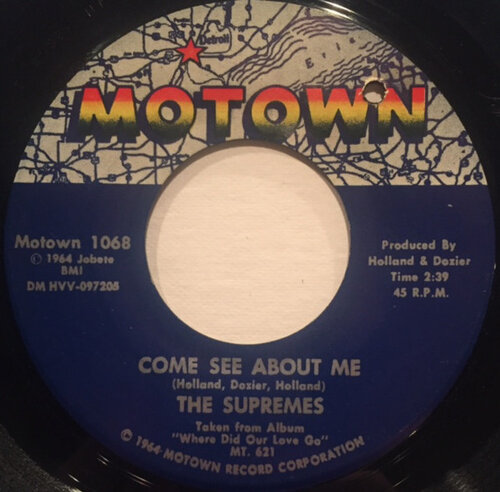

In addition to the title track, Where Did Our Love Go contained their next two hit singles, the upbeat “Baby Love” [Motown M 1066], and “Come See About Me” [Motown M-1068], all three signed H-D-H.

These three tracks collectively represent the first time a steady backbeat is prominently displayed throughout a song, providing a direct link to disco’s main rhythmic component. That common thread comes out even stronger on “Stop! In the Name of Love” [Motown MT1074], released in February, 1965, with its metronomic 116 bpm, then in April by “Back in My Arms Again” [Motown 1075], the last of five consecutive #1 hits, the latter two appearing in July on their sixth studio album, More Hits by The Supremes [Motown S-627].

Standing at the midpoint of the 1960s, I can only say…

“Baby, baby, I hear a symphony”

The Supremes, “I Hear a Symphony”

Leave a Reply