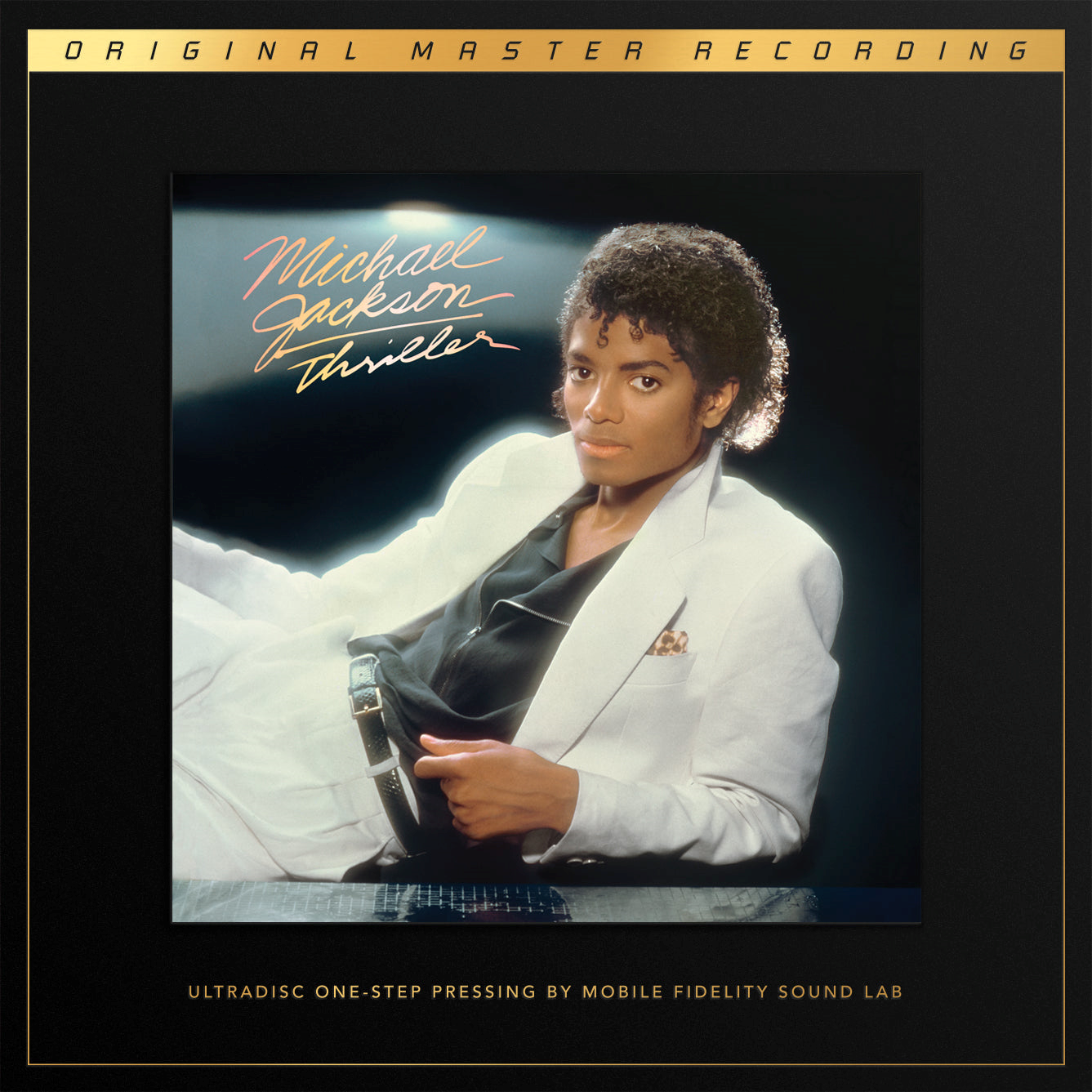

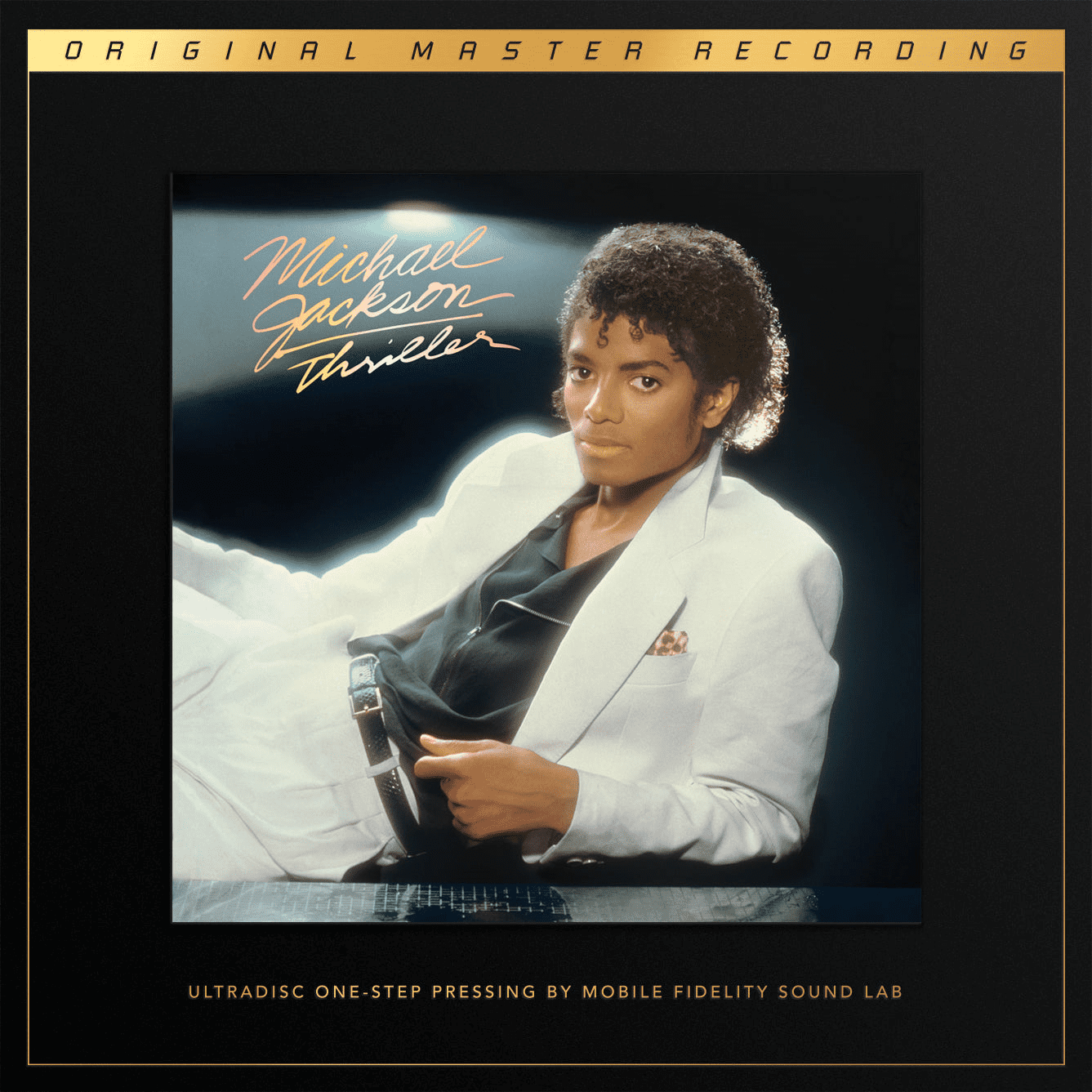

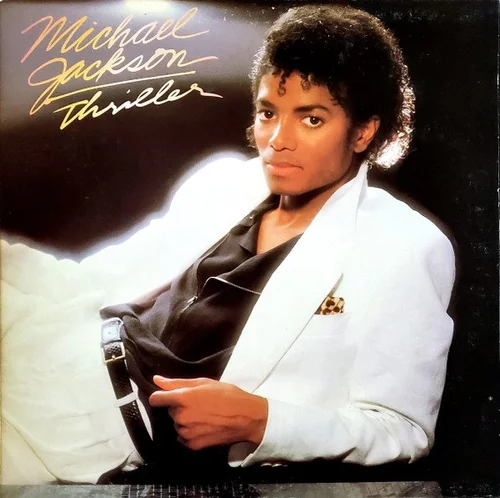

Michael Jackson

Thriller

Mobile Fidelity Sound Lab, Columbia Records – UD1S-042, Limited Edition, SuperVinyl, Slip Case (2022, Nov.), promo #P087 of 40,000.

Originally released on Epic – QE 38112 (1982, Nov.)

Ratings:

- Global Appreciation: 8.5

- Music: B (7.3)

- Recording: (5.8 to 8.7) avg. 7

- Remastering + Lacquer Cutting: 8.8

- Pressing: 9.7

- Packaging: Deluxe

Category: pop, post-disco, dance music, dance rock, hard rock, boogie, electro-funk, funk, afropop, ballads.

Format: Vinyl 180 gram LP at 33 1/3 rpm).

One Step beyond the dance floor!

When MoFi offered to send me an advanced promo for one of the most famous albums of all time, I couldn’t pass up the opportunity and thrill of revisiting a classic forty years after its initial release. “Famous” is the key word here—why was Thriller so famous?

After all,with Thriller, Jackson didn’t alter the course of music as Elvis did with “Heartbreak Hotel” and “Hound Dog”, or invent a brand new genre such as James Brown did with funk, nor was it as creatively groundbreaking as albums such as The Beatles’s Revolver and Sgt. Pepper. What Thriller did accomplish was set a record—pardon the pun—for best-selling album of all time. It’s a record it still holds today.

How many copies does that add up to? 70 million worldwide at last count, in 2021, according to Wikipedia. It was Jackson’s sixth studio album but first “#1” chart topper, a position it held for 37 non-consecutive weeks. It spawned 7 Top-10 singles and won 8 Grammy Awards.

Perhaps more significantly, through the medium of MTV, Michael Jackson “broke the colour barrier” by being the first black artist to receive regular rotation on that channel, in the process opening up the gates for others to follow. Powered in part by his strong stage presence, along with the tight choreography seen in the sophisticated cinematic-like music clips, Jackson was catapulted to “King of Pop” status, greatly expanding his already impressive fan base around the globe. But as the Royal Family’s King Charles might say, “You don’t get crowned “King” overnight!”

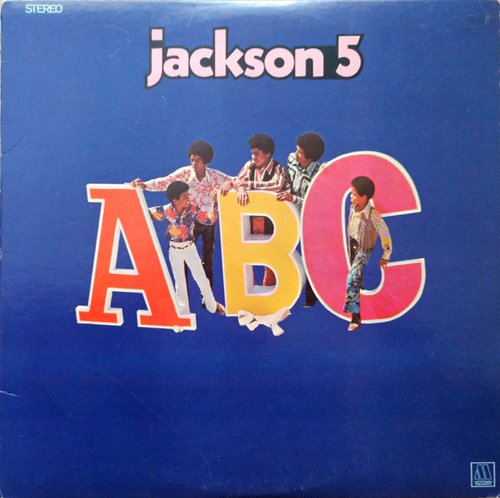

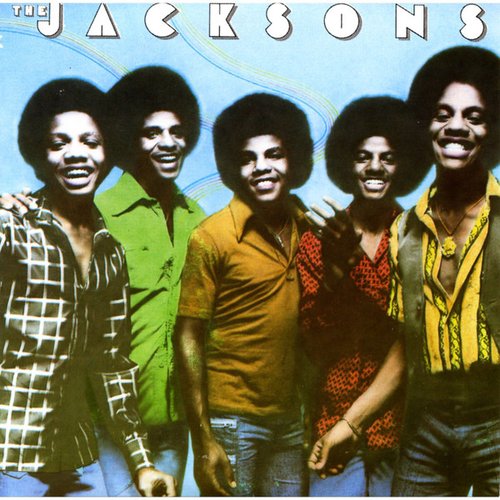

Managed by their father Joe, the Jackson 5, consisting of brothers Jackie, Tito, Jermaine, Marlon and youngest sibling Michael, were part of the Motown family. They climbed the music charts from 1969 to 1973 thanks to huge hits that included “I Want You Back”, “ABC”, “I’ll Be There”, and “Dancing Machine”.

From the get-go,exhibiting immense talent, showmanship, and determination, Michael demonstrated he was the rising star of the group, dominating the dance floor with his “robot dance” routine on television specials spanning the decade. In 1976, after a lull of hits, the quintet switched from Motown to Epic Records, with brother Randy replacing Jermaine.

Having swapped the “5” for an “s” at the end of the Jackson name, the band gained greater artistic control over their music direction, enjoying such major hit singles as “Enjoy Yourself”, “Blame It on the Boogie”, and “Shake Your Body (Down to the Ground)”.

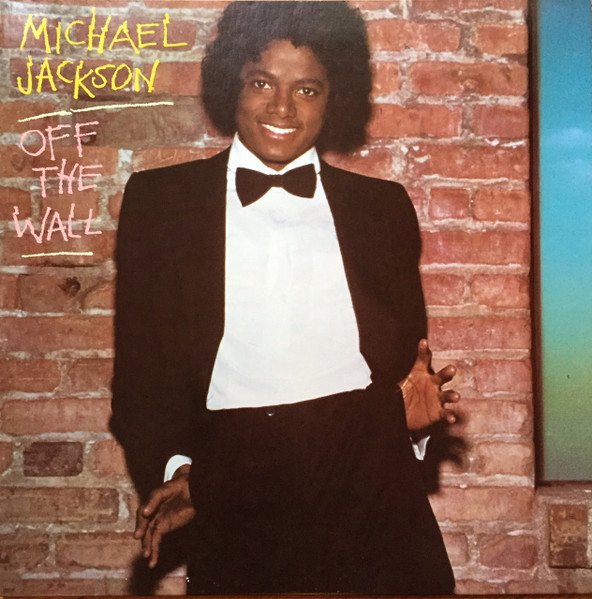

A major turning point arrived in December 1978, when Michael, who was, by then, both a contributing member of the Jacksons and solo artist, joined forces with renowned producer, composer, and arranger Quincy Jones for his fifth—but first for Epic—studio album, Off the Wall,originally released in August, 1979. Clearly departing from the past “Jackson sound”, the album signalled the increased individuality of the maturing singer just shy of his twenty-first birthday, who was now developing his own unique style.

Comprising the dance floor hits “Don’t Stop ‘Til You Get Enough”, “Rock With You”, and the title track, Off the Wall offered a glimpse of what lay ahead. A solid disco album, it would go on to sell over 20 million copies worldwide. Message to MoFi: please add that LP to our collective One-Step 45rpm wish list.

In October 1980, the Jacksons released two final disco hits with “Can You Feel It” and “Walk Right Now”. In the interim, Off the Wall had garnered both many accolades from music critics and strong sales success.

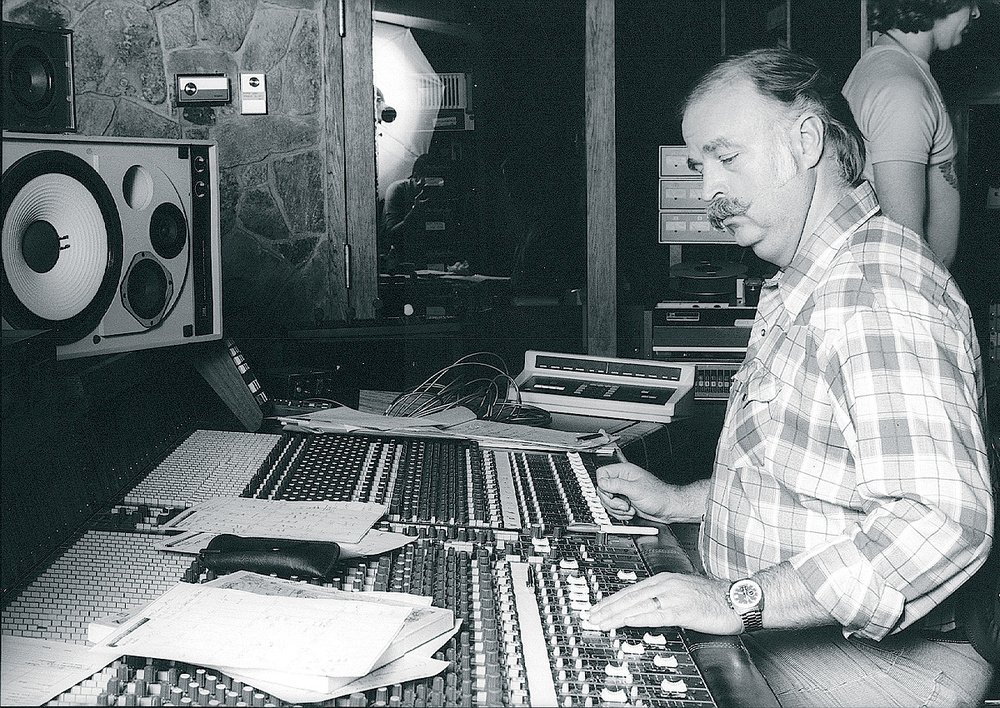

By 1982, disco’s popularity was in sharp decline, and in order to conquer the masses, Michael needed to pivot towards a different Beat. In April, he and Jones teamed up once more but this time the musical palette expanded to include a stronger pop feel, with fresh ingredients stemming from post-disco, dance music, dance rock, hard rock, boogie, funk, afropop, and ballads. Engineer Bruce Swedien, who sat in the pilot seat for Off the Wall, reprised his role, recording and mixing Thriller at Westlake Audio and Ocean Way Recording, in Los Angeles, California.

A disciple of Universal Studio’s whiz engineer Bill Putnam, Swedien is one of those old school guys whose impressive résumé lists countless jazz and big band greats, as well as a who’s who of sixties and seventies soul singers, among others. Preferring to get the sound right in the studio rather than “fix it in the mix”, he shared one aspect in particular with many audiophiles—he was an imaging and soundstaging maniac. In fact, to preserve or, perhaps, enhance soundfield cues, he created what he dubbed the “Acusonic Recording Process”, wherein rather than record an instrument with a single microphone and track, then “panning” it between left and right channels, he used a pair of mikes and two tracks on every instrument to capture an instant stereo image. In other words, instead of employing a traditional 24-track tape machine to record 24 individual instruments or sounds in mono, his method used 12 pairs of individual instruments or sounds in stereo, thereby greatly increasing the breadth, depth, and width of the soundstage.

In interviews, Swedien said he avoided compression and limiting as much as he could, preferring to “ride the faders” to adjust the gain when need be. As we shall see, however, that doesn’t seem to have always been the case. The same could be said for EQ, whose use he said was minimal most of the time.

Armed with a personal collection of 105 microphones, Swedien wasn’t afraid to experiment to get the sound and texture he was after. Case in point is the famous drum track behind “Billie Jean” that leaves no foot untapping. The playing is by a real drummer—not a drum machine as was often the case in ’80s dance music and other tracks on Thriller–captured in a live take with the drum kit on an unvarnished, 8ft² floor riser elevated ten inches above the ground. To get the sound he wanted, Swedien inserted a couple of heavy cinder blocks and a mike inside the kick drum.

Swedien’s fanatical hands-on approach for getting a clean, punchy, articulated kick sound was first explored on Off the Wall‘s “Rock With You”, but employed here with greater emphasis. During Jackson’s vocal tracks, lighting in the studio was reduced to a minimum to deprive visual senses of stimuli and enhance the auditory experience.

And now, for MoFi ‘s 40th Anniversary Edition….

Unlike previous Ultradisc One-Step releases that consisted of two 45 rpm LPs, this one is the label’s first to comprise a single 33 1/3 rpm LP, which explains the slip case’s thinner half-inch profile, a format that’ll surely be welcomed by record collectors bemoaning their lack of shelf space. I particularly like the simple side opening that dispenses with needing to open a box cover to retrieve the LP. If you store the record library-style with the opening towards you, you can simply pull out the LP from its slip case. If this same concept could be applied to the UD1S double-45 rpms, it would make things easier and more environmentally-friendly. The deluxe charcoal background with gold-coloured lettering and trimmings, which frame the original cover art, by famed photographer Dick Zimmerman, in a reduced 8 1/2 x 8 1/2 inch square, has a nice soft texture to the touch. The whole fit feels very elegant and classic—well done!

Pulling out the contents from the slip case, the first thing we see is a rigid “full-size” paper-thin gatefold replica of the original release with MoFi’s Original Master Recording strip at the top in the same pink hue that matches the back cover lettering. Opening it, you get the exact same centerfold of the singer found in the original jacket. MoFi also included a rigid reproduction of the original inner lyric / credits sleeve. Contrary to previous One-Step releases, there’s no sheet explaining the one-step process.

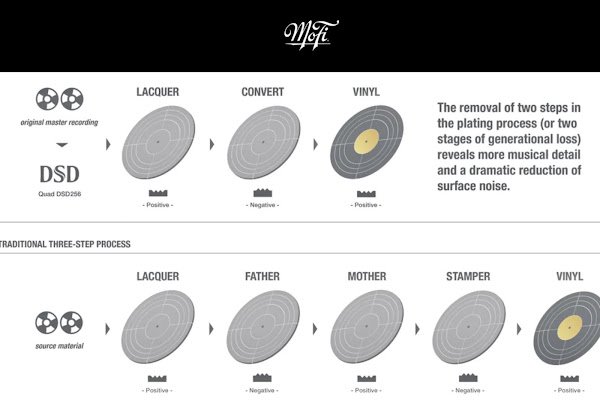

For those unfamiliar with it, here’s what it is in a nutshell: Whereas a normal ‘three-step’ release utilises the following chain: lacquer + father + mother + stamper, the one-step method skips the father and mother intermediary steps, going from master lacquer directly to stamper or, as it’s called in this case, “convert”. There’s a limited number of pressings that the delicate convert can withstand in the typical press before audible deterioration creeps in—around 1000 for 180g LPs. That means that between 30 and 40 sets of lacquers-converts were required to complete the run of 40,000 copies. Of course, like any pressing, there may be minute sonic differences between lacquer-converts but I was told that all the settings were “locked in” for the entire run to preserve sonic uniformity.

Think about it. Engineer Krieg Wunderlich had to do the exact same cutting job 30 to 40 times over! Therefore, the use of a DSD source instead of the original analog master tape—played over and over—makes sense. It should put to rest, or at least into perspective, the notion advanced by some that by converting to DSD, MoFi should lower the prices of their One-Steps and eliminate limited quantities, implying the label saves time—all it has to do is push a button and press as much as it wants. That’s true with the three-step method, because you only cut the master once and go back to the mother when the stamper needs to be replaced, but as with this Thriller release, there is no mother to fall back on. The whole job has to be redone.

Finally, we reach the treasured vinyl, inserted in a cardboard sleeve printed with similar art work as the slip case cover, with the track titles printed on the back side, and the LP further protected by MoFi’s inner HDPE sleeve inside a white folded cardboard. As usual with MoFi, no attempts were made to duplicate the original Epic label. Instead, the same design was used as for their other UD1S LPs.

Engineers Krieg Wunderlich and Shawn R. Britton transferred the original 1/2″ 30 IPS analog master source to a DSD256 format. This was then passed through an analog console and on to the cutting lathe. Inscribed on the dead wax on side A was the notation A4, on side B, B3, indicating my copy’s 4th and 3rd master cuts respectively. Plating and pressings were done at RTI in California. Both sides were visually perfect, glossy, and dark, though when held up to the light I was still able to see through the record. RTI’s pressing was well centered and flat. On the first run-through of the album, I detected a few low level noise cracks between certain songs, but then things seemed quieter upon second playing. This could be because MoFi chooses not to dehorn their stampers, so our styluses “polish” out some of the previous tics.

I don’t have an original or early US pressing of Thriller. Originally done by Bernie Grundman, Grundman explained in web interviews that Thriller was such a big seller that he had to remaster and cut it on multiple occasions because the metal parts kept getting used, and he found that he preferred his later pressings that were cut at a quieter level than the earliest ones cut louder. The closest vinyl comparisons I had on hand were the Canadian first press on Epic distributed by CBS [Epic QE 38112], and a Mexican first-press [Epic LNS-17406].

I always felt the 1982 Canadian pressing, including what I heard of it on the radio and in clubs, sounded disappointing and slightly below average for pop recordings of that period. That said, the sound quality of the average record in ‘82-83 was going downhill compared to that of just a couple of years prior. More and more studios were introducing primitive digital instruments, samplers, and equipment, and the music industry as a whole was heading towards a higher level of dynamic compression, which was squeezing out warmth, life, and tonal fatness, in exchange for increased loudness. There’s a general demarcation point that separates pre-1982 and post-1982 recordings in terms of sound quality, with 1984 and up really worsening. Yes, there are exceptions—Depeche Mode UK 12-inch singles that sound incredible, as do some well-mastered tech house—but these exceptions proved the rule.

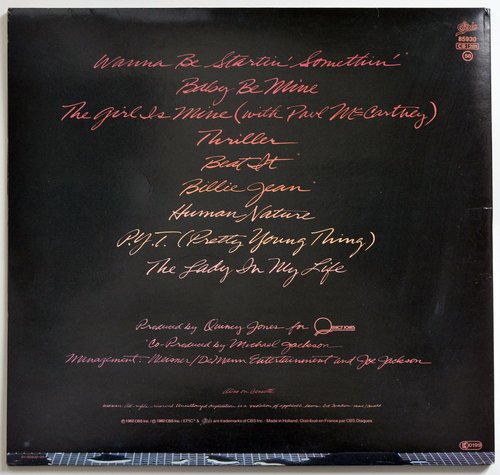

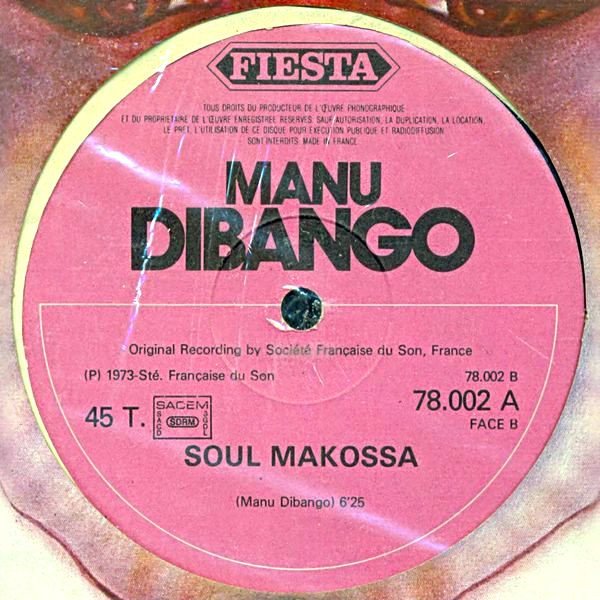

If you wanna start somewhere on Thriller, then “Wanna Be Startin’ Somethin’” seems a good choice. With it’s three snare strikes, it catapults us into a frenzied, funky, shuffled groove driven by a Univox SR-55 analog drum machine plugged directly into the console, before adding brisk brass riffs and repeating lyrics.

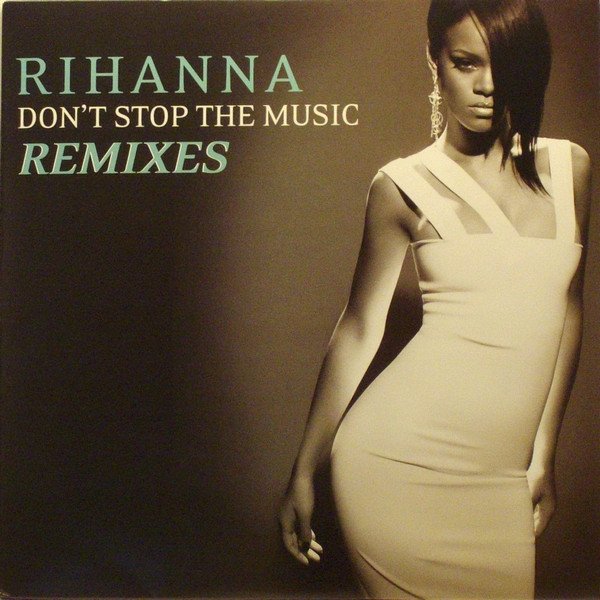

The song’s coda is an interpolation (a replayed sample) from Manu Dibango’s 1972 hit “Soul Makossa”, and which Rihanna’s 2007 hit “Don’t Stop the Music” sampled from Jackson’s track. Interestingly, Jackson’s song was first recorded in 1978 for Off the Wall but ended up being left out—perhaps because the album’s”Working Day and Night” was too similar in style—and re-recorded in 1982 for Thriller. Unlike Off the Wall, which I’ve listened to several times on my current system, know by heart, and love for its sonics, I realized I’d never listened to Thriller in its entirety in my home. Starting with the Mexican pressing, the treble on “Wanna Be Startin’ Somethin’” was grainy and dirty, the sound lacked transparency, the soundstage was flat and narrow, and Jackson’s voice sounded muffled and was plagued with sibilants. The only minor redeeming quality was the better-than-expected weightiness of the synth bass riff. My overall take on this version? Boring and compressed.

Second in line, using the same song, with volumes matched, was the Canadian first press. First thing I noticed was its lack of bass and groove compared to the Mexican press. It did, however, provide cleaner treble and less-muffled vocals, although the latter could sound too forward in the upper mids, with too much artificial reverb. The winner? A toss-up between two mediocre presentations.

I then put on the MoFi, on which “Wanna Be Startin’ Somethin’” sounded very different than it did on the two previous albums or than I’d ever heard it on the radio. First off, the MoFi was much more transparent at all frequencies. The biggest improvement was in Michael’s vocals, which were more dynamic, natural-sounding, cleaner, tonally more balanced, extended, and possessed greater jump factor. Also was the elimination of that unpleasant upper mid peak the previous pressing exhibited. Some sibilants were still present, but these seemed inherent in the recording, and while frequencies over 6kHz or so still sounded a bit sandy, they were definitely less distorted than on the two other pressings. The guitar riff on the left was better outlined in space and easier to follow, as were the sounds of all instruments. Most intriguing was the soundstage, which was much more developped with the MoFi, especially width-wise, with some sounds seeming to appear directly at my sides! It was so different than what I was used to I thought perhaps MoFi had used an alternate mix from 1982 whose existence I was unaware of. I thought the same thing when the multiple percussive triplets startled me. One of the strangest effects I heard was when Jackson sings “You’re a vegetable”—his voice was so clear and the imaging in the “side-surrounds” of the soundfield so spooky real, I turned my head to locate the source! When I went back to the Canadian copy to see if those effects were already there or if the MoFi indeed used a different mix, I was surprised to hear that it was the same mix. Those sound effects were there all along but they were buried in the haze of tape degeneration or pressing-step losses. Clearly, there was no contest—MoFi’s remastered version trumped the others handily. My only nitpick: I would have liked a touch more bass to augment the groove factor.

“Baby Be Mine” was not a hit commercially but is nevertheless a good song. Less compressed than the album’s other tracks, the MoFi version improved it by adding bass heft, reducing sibilants, and delivering finer treble.

While “The Girl Is Mine”, a duet between Jackson and Sir Paul McCartney, isn’t my cup of tea musically—I’m not a fan of ballads—I was impressed by how the One-Step process opened up the soundstage, lifted veils, and shined a light on both voices’ distinctive timbres and ranges.

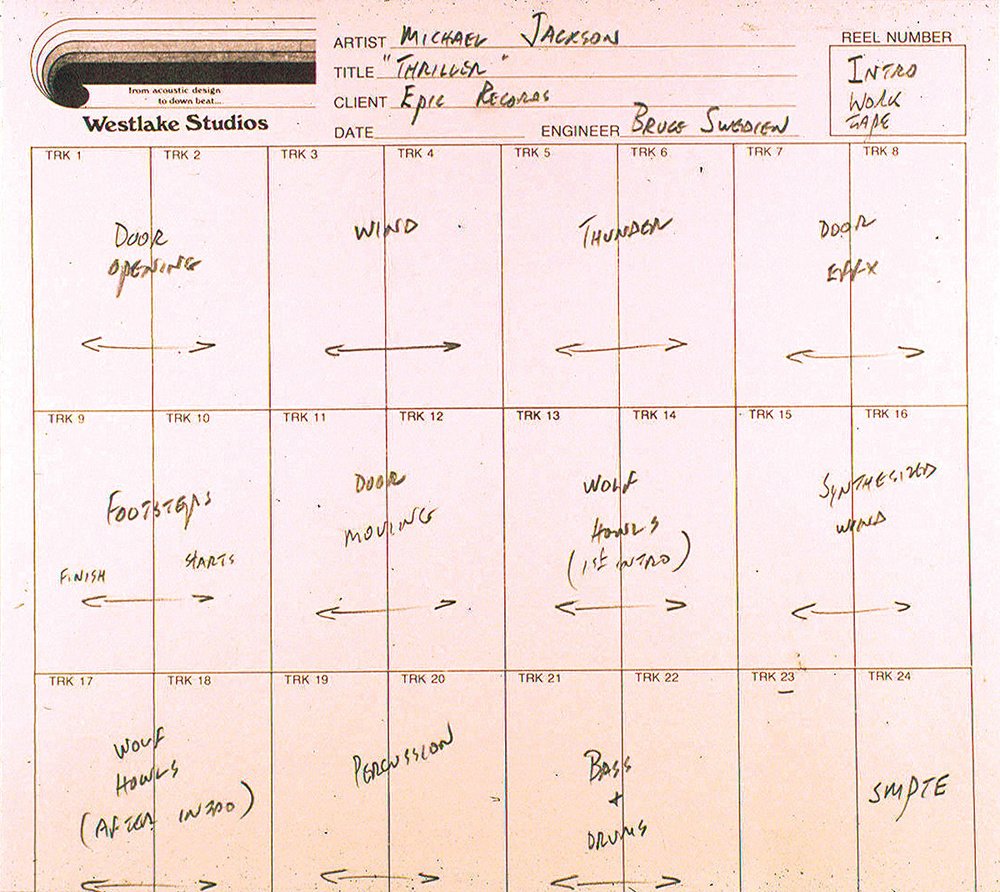

I always thought it was strange, not to mention unorthodox, that “Thriller”, the title track, would be chosen to close side A rather than open it, more so given the extended “spooky” intro. Speaking of which—those howling wolf sounds were in fact vocals by Jackson mixed in with some library-sourced material, and the door effects came from the creaking hinges of rented doors. I compared this track on all three pressings, and again the MoFi easily came out on top. For starters, the intro was impressive for its soundstage transparency and size. It was layered. Elsewhere, you feel the solid low end thwack of the door closing, while the stage-panning footsteps were startling in their clarity. The slow crescendo of the hi-hat was better rendered—in the two other pressings it seemed muted. And when the main beat and bass line take over, you sense the full measure of what the MoFi can deliver when tonal balance and detail are on point. All three pressings showed that this track always had lots of bass, but as opposed to the two regular LPs, which lack definition in the highs and dull the sound of everything, the MoFi maintained its composure and superior articulation right to the very end of the side, which is the worst position on a record for a track’s top end. The sequencer break towards the end had a thrilling clarity. The outro, featuring the legendary voice of horror movie actor Vincent Price, was distinctively crisp during the music, making it easy to follow his words even when the mix got more charged with the organ creeping in. The song rises and expands toward its macabre finale, until it abruptly ends on a reverberantly glorious, gory note.

“Beat It” is the hardest rocking song on the album, made rockier by Eddie Van Halen who, near his peak of popularity, and with his virtuosity and bravado on full display, played the song’s guitar solo, and he did it for free. The song’s famous cold-sounding gong-like intro comes from a Synclavier digital synth which was popular in the ‘80s. On all three pressings, this seems the most dynamically compressed track on the album. Even the MoFi version, which is better and cleaner than the others, had trouble escaping its inherent recording limitations, but that’s how most hard rock was recorded back then. The VU meters probably weren’t swaying far from the zero line. I remember when this song came out, how even on the radio and in clubs it sounded less impressive than the other singles from Thriller.

“Billie Jean” remains the club favourite even after all these years, and my favorite song on the album. The winning recipe relied on Louis Johnson—of the Brothers Johnson–having his bass instrument plugged into a DI (Direct Input) with a UTC transformer inside, giving it that warm, fat, meaty sound, with the drums driving its momentum underneath. The entire drum and rhythm section was recorded, with no noise reduction, on a separate 16-track machine to keep the noise floor lower than on the 24-track (the greater the number of tracks, the higher the noise floor). Those string sounds in the mix? They were real—from a violin, viola, and cellos. Again, the MoFi offered the best presentation of the bunch, especially for the clarity of the vocals, hi-hat cymbal, and the top end extension.

Finally “P.Y.T. (Pretty Young Thing)” was the second best-sounding song on the MoFi, just after “Thriller”. The instrumentation has mostly Minimoog and analog synths that give it an electro-funk boogie style. The tonal balance was near-perfect, with the bass articulation and crunch sounding so darn good you want to crank it up! (At least I did.) The punchy staccato bass was sharply defined and fast. One of the sonic highlights of the song was the panned robotic vocoder-type vocals in the chorus that give off that future-funk vibe.

For those on the fence about this new release because of DSD being in the remastering chain, I’m on record, after having done extensive listening and comparison tests following the DSD “revelation”, as concluding that this digital intermediate stage did not interfere in the vinyl-sounding process. In fact, it was used in some of the best-sounding records in my collection, such as the One-Steps of Santana, Monk, Marvin Gaye, Yes, Blood, Sweat & Tears, and Carole King, as well as regular MoFi’s of such artists as Alan Parsons, Aretha Franklin, Bacharach-Costello, Grateful Dead, Jeff Beck, and many others. My experience-based opinion is that DSD should not deter someone from buying MoFi’s Thriller based on sound quality.

The One-Step minimalist approach—just like an accurate crossoverless single wideband driver—can be wonderful but it can also be a two-edged knife. It is so transparent than any sonic subtleties, including multitrack layers and overdubs, will become clearer and more distinct from the forest. It’s akin to seeing for the first time an ancient painting after its restoration; hidden layers will appear that were shrouded in time.

In the end, if you enjoy listening to Michael Jackson or Thriller, and don’t mind the sonic peculiarities of recordings from the early ‘80s, then this new 40th anniversary MoFi One-Step remastering is, by far, the best-sounding version of this album I’ve heard in my system, period. You might even think that on some songs you’re listening to a remix, when in fact you’re just hearing the original master tape more accurately than ever!

To the Thrillers that came before it, MoFi’s message is clear: “Beat It”!

Personnel:

- Michael Jackson – main vocal.

- Becky Lopez, Bunny Hull, Howare Hewett, James Ingram, Janet and LaToya Jackson, Julia, Maxine, and Oren Waters – backing vocal.

- Jeff Porcaro and Ndugu Chancler – drums.

- Paulinho Da Costa – percussion.

- Greg Philliganes, James Ingram, Louis Johnson, and Steven Ray – handclaps.

- Louis Johnson and Steve Lukather – bass.

- David Williams, Dean Parks, Paul Jackson, and Steve Lukather – guitars.

- Eddie Van Halen – solo guitar (“Beat It”).

- Anthony Marinelli, Bill Wolfer, Brian Banks, David Foster, David Paich, Greg Smith, Michael Boddicker, Rod Temperton, and Steve Porcaro – synthesizer.

- Greg Philliganes, James Ingram, and Tom Bahler – keyboards.

- David Paich – piano.

- Larry Williams – saxophone, flute.

- Bill Reichenbach – trombone.

- Gary Grant and Jerry Hey – trumpet, flugelhorn.

Additional credits:

- Produced by arranged by Quincy Jones.

- Co-produced by Michael Jackson.

- Recorded and mixed Apr. to Nov. 1982 at Westlake Audio, and Ocean Way Recording, Los Angeles, CA.

- Engineered by Bruce Swedien, Don Landee, Humberto Gattica, assisted by engineers Mark Ettel, Steve Bates, Matt Forger.

- Original mastering and cutting– Bernie Grundman.

- Remastered and lacquer cut by Krieg Wunderlich, assisted by Shawn R. Britton at Mobile Fidelity Sound Lab in Sebastopol, CA.

- Plated and Pressed by RTI, CA, USA.

- Photography by Dick Zimmerman.

- Typography (lettering) by Mac James.

For more from Claude Lemaire visit…

Leave a Reply