This article first appeared in PS Audio’s Copper Magazine.

The first time I walked into the Fillmore East (located in the heart of the seemingly dangerous newly-named neighborhood the East Village on Second Ave. and Sixth street) was on Saturday, November 23, 1968.

I went to see Iron Butterfly because I loved their huge hit album In-a-Gadda-Da-Vida (actually named after a very stoned way of saying “In the Garden Of Eden”).

The album was an FM radio staple. The song “In-a-Gadda-Da-Vida” comprised the entire second side of the album and lasted 17:05!

The song (and album) was groundbreaking and set all kinds of sales records. It was the first actual Gold album certified by the RIAA as reaching sales of 500,000 copies. Up until then, a “gold record” meant $500,000 in sales (about 175,000 actual album sales). 500,000 actual album sales was much larger in dollar value to a record label, as list prices for albums were $2.99, meaning that 500,000 records sold was about $1.5 million dollars billed to the record label.

There were two other acts on the bill that night: the Youngbloods and Canned Heat.

I was a fan of the Youngbloods as they already had an FM radio hit called “Get Together” released the year before. Their style was very much a sound of the times folk-rock with a chimey Byrds-like guitar sound. As the opening act, their laid-back style kind of eased me into my first Fillmore East experience. I remember buying a ticket to the show at the New Yorker book shop on 89th Street off Broadway. It was $3.00!

I had had two previous live concert experiences: August 5, 1966 seeing the Animals at the Wollman Skating Rink in Central Park, and seven months later, attending an Easter Sunday afternoon concert at the RKO Theatre in Manhattan. It was a 10-band bill with Mitch Ryder and the Detroit Wheels and Wilson Pickett as headliners. The opening acts were “The Cream” (that’s how they were listed), and The Who. Both bands were unknown at the time. Every artist played for about 15 minutes. The Young Rascals had the number one record in the country that week with “Groovin’” so they played five songs. These kinds of multi-act revues were common in those days. Remember that the Beatles only played seven songs – a 29-minute set! at Shea Stadium.

What the Fillmore East did was finally give artists a wide berth in performing. Most headliners played about an hour and most undercard acts played 30 to 40 minutes each. This way, Bill Graham could “turn” a stage around for two full shows – at an 8:00 p.m. and an 11:30 p.m. start time.

This was all new and exciting at the time.

The upstairs balcony at the Fillmore was a drug supermarket with the smell of weed and hash absolutely saturating the air and wafting into the balconies.

I came with lots of weed but that was like bringing a hooker to Las Vegas. Completely unnecessary!

I settled into my seat at the 8 p.m. show and heard the Youngbloods, who were promoting their upcoming album, Elephant Mountain.

To me, it was excellent. Just being there was a thrill, like I was emancipated from my boring existence. The thought of being critical of the experience never entered my mind. I had given myself over to the dark forces of rock and roll and was prepared to go wherever they took me.

Two years before, I was seriously turned on by the blues. First through the Paul Butterfield Blues Band and then by John Mayall’s Blues Breakers with Eric Clapton album. Cream then followed, and through reading interviews with Clapton and Mike Bloomfield, I got turned on to Albert King.

Canned Heat, the second band on the bill at the Fillmore, was a boogie-style blues band. If you know John Lee Hooker’s style you will know what that means. Yes, they played songs, but they also jammed to a shuffle that sounds like a drone but actually leaves all sorts of room for the players to stretch out and…play.

Canned Heat had a lead singer named Bob “the Bear” Hite, a good vocalist, an accomplished guitar/harp (harmonica) player named Al “Blind Owl” Wilson and a guitar player named Henry Vestine.

As this was the new music of the day, performers were expected to jam and improvise. That was part of the late ’60s music scene. Everyone in the audience was expected to be stoned and the bands were the pied pipers (and probably even more stoned).

That’s exactly how I remembered it.

Why write about this now?

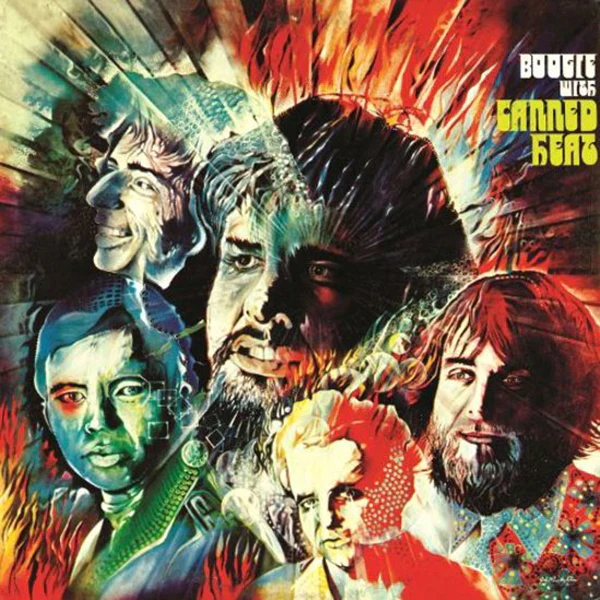

Because, as I was going through my record collection recently, I found a couple of Canned Heat albums which I haven’t listened to since I bought them in 1968 and 1969: Boogie with Canned Heat and Hallelujah.

Listening to these albums immediately took me back to that first Fillmore East experience.

Many of you probably know the most famous of all the Canned Heat songs, “On the Road Again.” This song has stood the test of time (It is on the Boogie with Canned Heat album) and has been in dozens of movies and commercials. It is their one lasting legacy.

Canned Heat was the quintessential “biker band” before that was ever a description. Just a greasy. hippie blues band. There were others, like Mother Earth, but the idea of a “boogie band” began with them. Much less sophisticated than the Allman Brothers. England has their own version of this kind of rock: Status Quo.

Here’s the thing – I was just learning how to play the blues at that point and trying to figure out Mike Bloomfield, Eric Clapton, and Albert King. It was hard learning their styles. These players were extremely gifted and accomplished. Way more than I could fathom. I needed another “mentor” player. Someone better than me but accessible enough to understand the construction of a blues solo.

Then I saw Henry Vestine and Canned Heat.

Here was a guy who had an approachable style I could copy (almost) and further my development. He also had a guitar tone I could copy. Clapton had his Les Paul guitar and Marshall stack, Albert had his Flying V guitar and his Acoustic amplifiers, and Bloomfield had his Fender Telecaster guitar and Fender amps.

At that time, I had a Gibson SG and an Ampeg V4. For whatever reason, when I came home after the show, I could get close to Henry’s guitar tone. Enough so to emulate his playing.

This was the real value of going to the Fillmore every week. You saw your heroes, came home, strapped on the guitar and I could fantasize that one day it could be me.

Henry Vestine gave me that lifeline.

His playing was just a couple of levels above me. No, he wasn’t the technician like Clapton, or have the speed of Bloomfield or the mind blowing idiosyncratic phrasing of Albert King.

Henry was just a lunch bucket, blue collar blues player.

I don’t refer to him much, but re-listening to these Canned Heat albums has been a revelation. A throwback to a simpler time of quality, earnest performances, steeped in the rich tradition of the blues at a time when white musicians not only became enamored with an original American musical idiom but did everything they could to bring the actual originators to the predominantly white rock audience. Experiences like these opened the whole world of the blues to me and to thousands of American teenagers at the time.

This is not about political correctness. This is about giving credit where it is due to my evolution as a player.

Twisted Sister is not a blues band, although most early heavy metal bands evolved from a blues format.

Pink Floyd (certainly not a blues band) was named for two blues musicians (Pink Anderson and Floyd Council). That’s how much the blues was injected into the rock music landscape of the late 1960s.

Canned Heat was the kind of band that Pigpen of the Grateful Dead could have put together as a solo project.

Henry Vestine of Canned Heat got me closer to my understanding of blues guitar, and that opened the door for me.

Thank you Henry…and Canned Heat.

For more, visit PS Audio’s Copper Magazine.

Leave a Reply