And what you can do about it.

Top image by OpenClipart-Vectors from Pixabay. All other images by Jonson Lee.

If someone were to ask me what I think is the most important sonic attribute in sound quality, my answer wouldn’t be imaging or soundstaging, it would be volume. More than anything else, volume determines if the listening experience turns out to be a wow or a meh. I’m not just talking about the overall loudness but also how it fluctuates from moment to moment, which is called dynamics. And the practice of reducing dynamics is called compression.

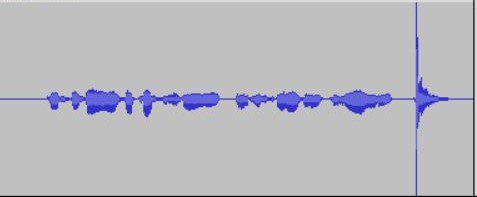

To illustrate how compression works, I recorded a short audio clip where I spoke softly for a while and then clapped loudly at the end. Below is a waveform image of the raw recording:

Let’s say the excerpt is intended for a radio commercial. But the clap at the end, which peaked at the ceiling, takes up so much room it prevents me from increasing the overall level, which means the quieter parts preceding the clap can’t be made to sound louder. As it is, my voice would sound tiny next to my competitors’ more thunderous voices. To get around the issue, I compressed, or shrunk, the volume of the clap to create some room, and then maximized the overall output level as follows:

Despite its usefulness, the idea of compression doesn’t sit well with us audio lovers. We often criticize a recording for sounding compressed, i.e. loud and lacking in high or low frequency extension. Yet, compression is used in every audio production step. It isn’t evil. It’s done for practical and musical reasons, to make the recording suitable for home listening or sound punchier. What I am putting on trial is compression done excessively to a point where it hurts the music.

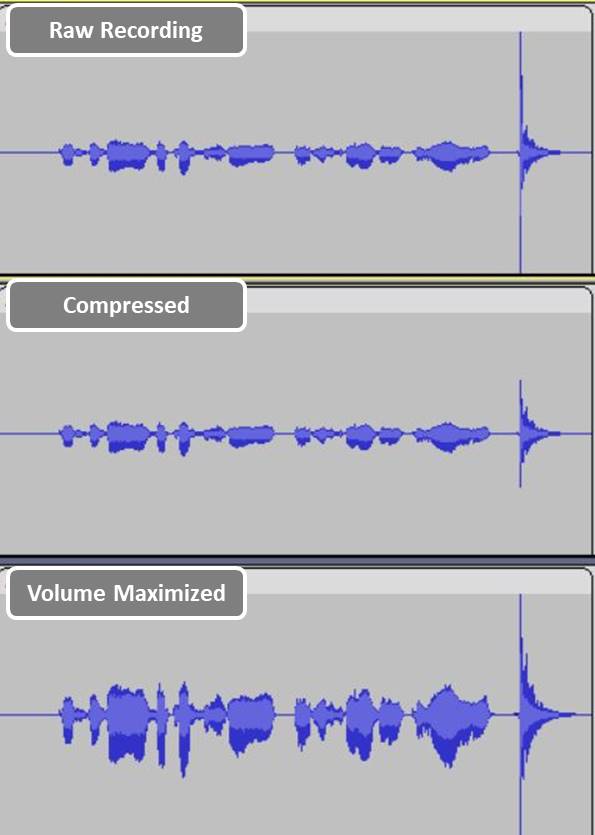

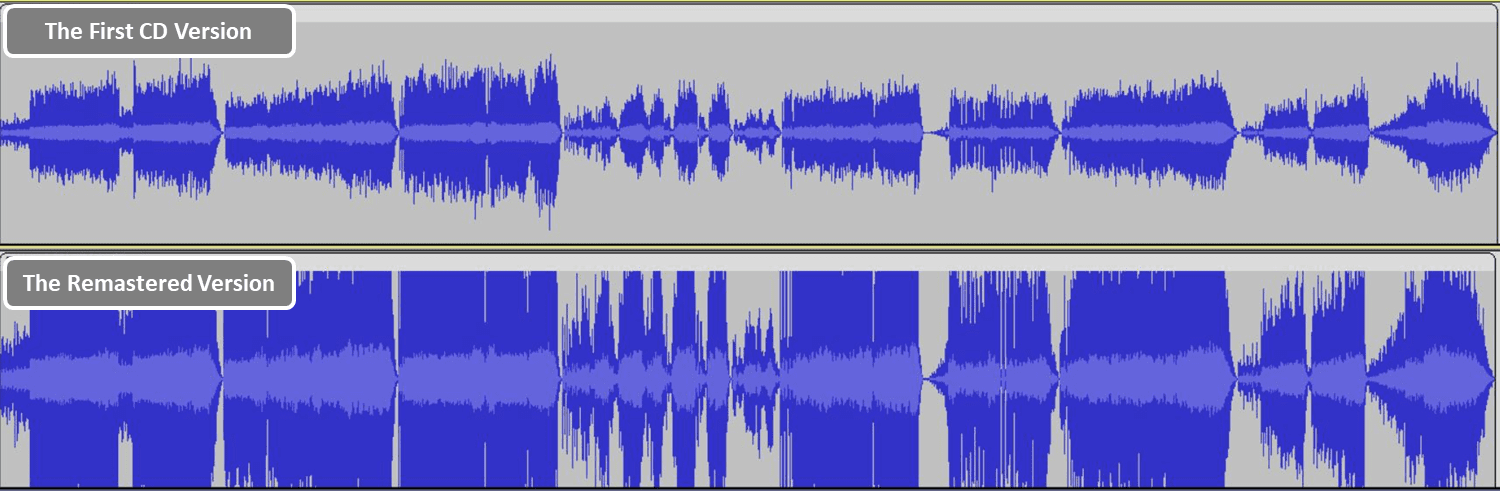

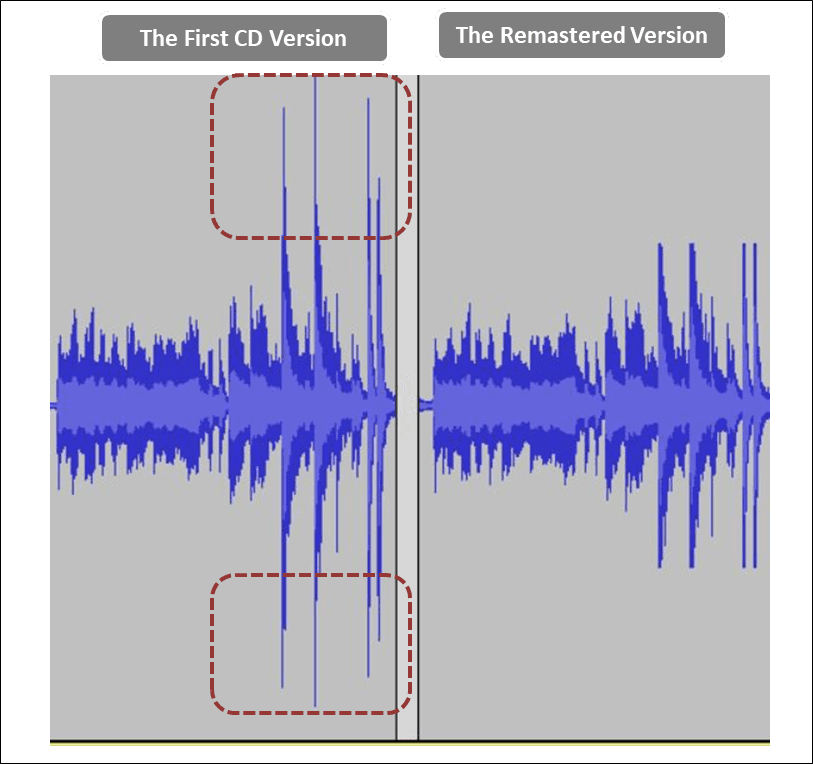

Classic albums, such as the Eagles’s Hotel California, are the most obvious victims of the practice. Below is the comparison between its very first CD version (top) and the 2013 remastered version (bottom):

You can see that, with the remastered version, almost all peaks were truncated to increase the overall level, resulting in a consistently loud, flat waveform.

What exactly got lost in the process? You can see it when you match the volume between the two versions and zoom in. Below is the comparison between the two versions, zoomed in on the part in the title track where Don Henley sings “They stab it with their steely knives…”, followed by a loud drum attack. I indicated the volume truncation of the drum attack in red squares.

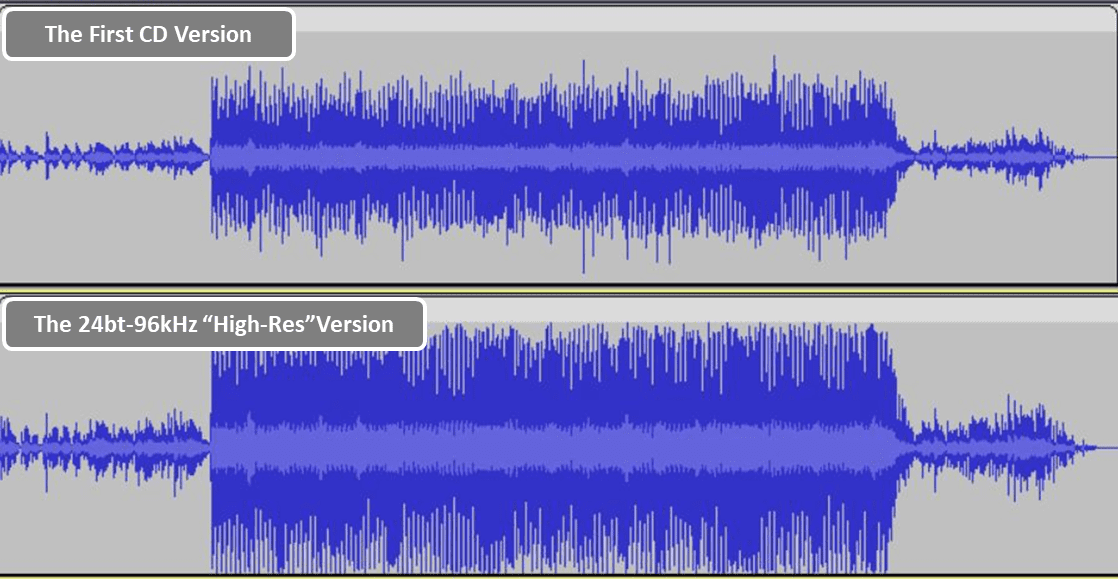

You think those 24-bit “high resolution” files are necessarily better? Here is the comparison of two different versions of one of my favourite songs, “The Stranger”, by Billy Joel:

You see the same story here…

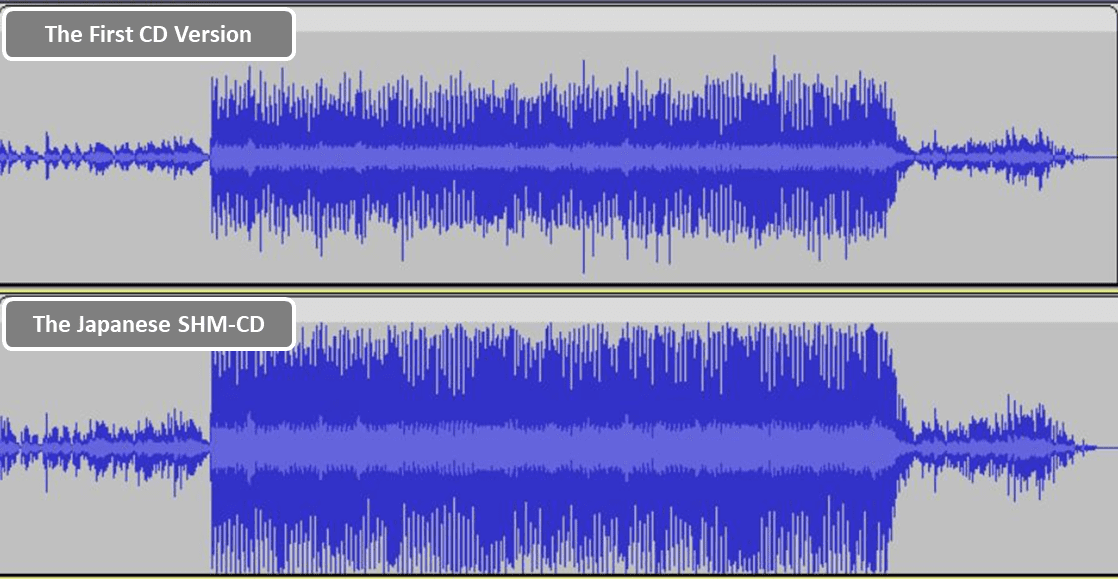

Or how about those fancy Japanese remasters? The labels’ marketing is aimed specifically at audiophiles, so you would think they would focus on delivering less compressed sound. Think again. From a Japanese “audiophile” remaster:

In all three cases, the intention seems obvious—to make the music win the loudness war. But it only bleeds with no victory because other tracks are mastered the same way. Like in many wars, no one wins.

Yet, every time one of these new versions comes out, it gets praised all over the Internet for its “bigger soundstage”, “more substantial bass”, “greater detail”, and even “wider dynamic range”. What’s going on here? The answer is: the volume. When it’s cranked up, you hear the more recessed parts of the music more clearly. In all three of my examples, I found the volume at the beginning to be at least twice as loud in the newer version than in the original CD.

And don’t get me started with streamed files from streaming services. They’re even louder than the remastered CDs, which indicates even more compression was added.

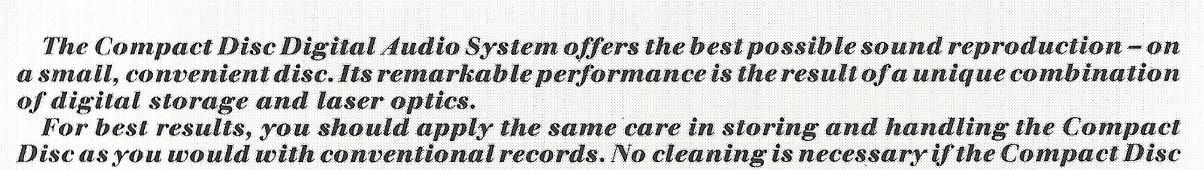

For those who want to hear digital music with the original dynamics preserved, the solution is simple. Just get the original CDs that came out in the late 80s and early 90s. It’s not always obvious to know which release was first, so look for clues, such as this message explaining what a CD is to an audience presumably unfamiliar with the format:

Another option is to do what I do—use Audacity software to test the CD. If the music on it is overly compressed, you can sell it if you own it or return it if possible. I don’t want to say that all remasters are guilty of over-compression—that wouldn’t be fair to the remastering engineers who have truly improved the recording’s sound quality through proper means—but be wary of releases that say “remastered” or something like “Special Edition”, especially since these tend to cost substantially more than regular CDs.

Most CDs of classic albums sold today were remastered, which likely means more compression than on previous releases. Further damage is being done by streaming services, while most of the pop recordings of the last few decades started off highly compressed. In today’s audio, over-compression is the order of the day. Many of us just don’t notice it because it has become the norm.

Music consumption today is a bit like contemporary life, in that we’re overstimulated by a loud, relentless stream of information. This is causing us to forget how to savour the music. That’s why, for the sake of peace of mind, I suggest we all occasionally make a conscious effort to break away from the relentlessness of it all. Pick up an old CD or LP that you know isn’t over-compressed and play the whole album through without allowing yourself to be distracted by anything else—especially not your cell phone.

I assure you it’ll be a great way to… decompress.

Leave a Reply