One of the things that impresses me most about PMA Magazine contributor Claude Lemaire is the man’s encyclopedic knowledge of popular music. If there was an edition of the game show Jeopardy! entirely focused on the minutia of who did what on any recording, I’m convinced Claude would have a legitimate shot at being inducted into the Jeopardy! Hall of Fame for how long his win streak lasted.

Claude is also a vinyl fanatic. He has about 12,000 LPs wallpapering a bedroom wall or, if they consist of the more collectable—read, pricey— variety, stuffed in record racks in his basement listening room. His affection for the LP format extends to his past work as a DJ, but even when it came to mixing, sound quality was important to Claude. He always gravitated to the best-sounding pressings.

He never adopted the CD format. He thought CDs looked cold, and sounded like they looked. “I didn’t like that they were small and silver. And I didn’t like the plastic jewel boxes or that as a DJ I couldn’t mix with CDs, at least not in the beginning, before advancements in DJ CD players made it possible. So when people were ditching their LPs for CDs, I bought up as many of their LPs as I could.” Looking at me quizzically, he adds: “How can you get emotionally attached to a CD?”

Color also plays a role in Claude’s choice of LPs. “I always preferred black vinyl. I don’t like it when they take the carbon out and it looks acrylic. I don’t much care for colored discs, either. They don’t sound as good, and if their color is too light, you can see the flip side of the record which makes it hard to cue the needle.”

Claude happens to be a friend of mine—he lives a 30-minute car ride from my house—but when he offered to participate in this column, I hesitated, for two reasons: his system is a combination of hard-to-come-by vintage and DIY products. I wasn’t sure that such a system would be a right fit for this column, whose purpose is partly to showcase products that people who might be interested in obtaining them could reasonably do so. Second, Claude is, how should I put this, a bit of an outlier when it comes to tweaks. He eschews most of the traditional ones in favor of using pieces of fabric and other materials in, well, non-traditional ways. In the end, I agreed to go ahead with this piece because not only does Claude’s system sound very good, but this column was never just about the gear, but about the people behind the gear. My decision did, however, prompt me, as a friend but also as his lawyer might, warn Claude that his opinions will likely elicit some unflattering feedback from readers. “I don’t care about that,” he said, comfortingly.

His subjective proclivities aside, Claude is no technical lightweight. He has a background in electronics and knows how to design audio gear, including turntables, amps, preamps, loudspeakers, and crossovers. He is also extremely well versed in measurements and electrical principles.

Claude cites two factors that helped him get into the audio hobby: his father, who loved music and appreciated good sound and encouraged a tween-aged Claude to get a decent sound system. And the dance clubs he’d visit, where sound quality took on an importance equal to that of the music that was playing. “In the 1970s and early 80s, the best clubs used speakers with the 15″ JBL drivers with the alnico magnets. They had a smooth, warm, and meaty sound that stayed with me my whole life. It’s something I’ve tried to emulate with my system.”

Claude’s speakers are based on an Onken design, which stipulates that the cone’s effective surface area should be equal to that of the vent area. In other words, a cone with a 38²in. effective surface area—about that of the 8” woofer cone in each of Claude’s speakers—should be flanked by 38²in. of total vent area, distributed on the baffle however. Claude doesn’t quite follow this 1:1 ratio, but the principle is similar. Most important with any speaker design, says Claude, is the positioning of the speakers in accordance to the listening chair.

The speakers’ sensitivity is rated at 93db. They’re made of Baltic birch plywood, a material Claude prefers over MDF. Each uses an outboard crossover, which Claude prefers over an internal one. “You can tweak and voice an external crossover constantly. Plus, it’s not good to have the parts of a crossover inside the cabinet. There’s too much air pressure and resonances.” Claude admits he hasn’t modified the crossover in ages. “I’m scared now if I modify something, I’ll lose the magic.”

Of tweaks, Claude’s versions of them are practically free. They consist mostly of room treatments made of mattress foam—the sort you might slip under a sleeping bag—and rugs. You’ll find them here and there—under the ceiling, on the back wall, at the foot of each speaker. What I initially mistook as discarded foam rolls in the corners were actually bass traps, tightened and shaped according to Claude’s listening preferences.

Claude points out that his tweaks may not be the most effective out there, but that they work because he spends countless hours fine tuning their placement. Other tweaks include the types of chairs that flank the one in the sweet spot and the little rugs in front of each chair, none of which can touch each other. These tweaks affect mainly the system’s low end—what Claude calls the difference between a decibel and a half decibel at 30Hz.

Then there’s the three-ring binder on each speaker enclosure, filled with “a precise amount of sheets, weighted subjectively by ear”, along with an unconnected metal super tweeter and wood puck placed strategically on the corners of his speakers, said to improve imaging and soundstaging. Behind the speakers is a love seat, placed just so, on top of which is an array of pieces placed just so: cushions, egg cartons, a folded rug. “It’s crazy, I know,” he says. I ask him how he tests his tweaks. “Constant AB testing,” he says. “I sit in the dark and listen and use a flashlight to test the tweaks.”

There seems to be so many tweaks inconspicuously scattered about, I ask Claude if he ever runs into a tweak he forgot he put there. “Perhaps on rare occasions,” he says.

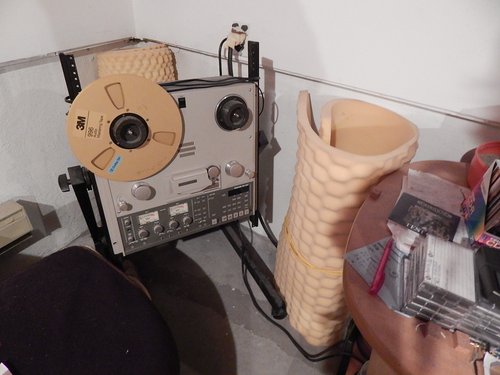

The pride of Claude’s system is his turntable, which he had a hand in designing and building, but which is mostly the product of his machinist / mechanic friend, Mario Paradis. Besides its Verdier turntable-inspired 30lb platter, the turntable, including its 16″ arm fitted with a Stanton cartridge, is made almost entirely of wood. Why such a long arm? “A longer arm tracks closer to the original tangent from the disc-cutter head. There will be less distortion than with a shorter arm.”

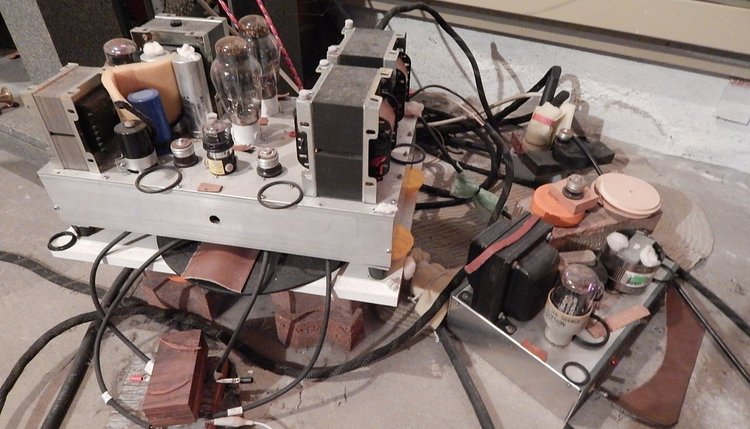

The tubed preamp is a DIY project built by a veteran electronic circuit expert with input from Claude. It comes with a bulky external power supply, also tubed. Claude explains to me the painstaking process he went through to find just the right tube types needed to give him the ideal balance between warmth and detail.

With all this vintage, DIY stuff, I ask Claude if he isn’t worried that if something breaks down he won’t be able to fix it or find the parts to do so. “It’s a trade-off,” he says. “I prefer trading a 100% guarantee that it can be fixed for the quality of sound I’m getting.”

What does he suggest to someone interested in exploring the DIY world? “You have to know what you’re doing,” he says. “Depending on the projects, there might be high voltages involved—300 to 400 volts. You can get seriously injured. I suggest starting with a kit, like my Audio Note amp, although mine was modified.” The Audio Note is a tubed single-ended design. Claude prefers single-ended circuits over push-pull ones, which deconstruct and rearrange the signal. “What’s great about Audio Note amps are their transformers,” he says. “Audio Note makes their own and they’re very good, especially the output ones.” While examining his amp, I ask if the sponge stuffed between parts on the chassis is meant to absorb magnetic fields. “It has nothing to do with the amp’s magnetic fields. I place pieces of different materials on the amp depending on the kind of sound I want to hear from the listening chair. If I want a warmer or softer sound, I’ll use cotton, sometimes rubber. I’m very good at intuiting what material is needed. Then it’s a question of finding where to put it and how much of it.” “So sometimes you don’t know where to place the material?” I ask. “Exactly,” he says. “And sometimes I’m surprised. I’ll end up placing the material somewhere that at first glance might seem to make no sense. That’s when I have to put my logical brain aside. It’s like Spock. He started off very logical then gradually became more human. I’m like that. I’ve gotten more subjective with time.”

His view on cabling? “It makes a difference but you don’t have to put a lot of money into it. I can use silver or copper, but for the dielectrics, it’s like tweaks. I look at the materials. I don’t like plastics or glass or acrylics. I’m more into rubber or leather, cotton, something more organic.

“And I avoid cleaning or connecting and disconnecting wires. I’m against that.” I must have looked at him funny because his eyes widen and he says: “I think in your Cable Guru article you say cleaning the ends improves the sound. To me, it kills the magic. I leave it all alone. The corrosion, the gunk. I don’t want to break the electron pathway that’s been built over years. It’s why I don’t want to try new gear in my system.”

So, what does the sum of all these parts sound like? After Claude had shut off the furnace, disconnected his TV, and unplugged a nearby freezer—a routine he practices prior to any serious listening—I was treated to a bevy of well-recorded LPs. Across the board, I heard a fleshy, vibrant presentation with excellent instrumental separation along a deep and layered soundstage. The musical environment was bloomy, expressive, and transparent, with a warm, buoyant undercurrent that propelled the music forward.

There was an overarching sense of stability to the scene. Singers and instruments were locked in space and sounded real-life explicit, in a way that managed to convey both the heart that went into the performance and the soul of the music. The sound’s inherent ability to bring out the humanity in a recording sucked me in each time.

At the end of my listening, I asked Claude what he liked most about the sound of his system. “It’s got body, it’s meaty, and it grooves.”

No arguing with that, brother.

If you have a system you’d like to talk about in our “No, I have the best system in the world!” series, let us know by dropping us a line here.

Leave a Reply