In the early 20th century, particularly the 1920s, America was alive with the hum of innovation and the beat of cultural renaissance. At the heart of this dynamic period, two engineers, Edward W. Kellogg and Chester Williams Rice, set out to transform the world of sound.

Edward W. Kellogg: The Scientist with an Artistic Streak

Born in the closing years of the 19th century, Edward Kellogg was an astute observer from a young age. He grew up in a rapidly industrializing America, where the lines between science, industry, and daily life blurred more each day. This dynamic backdrop might explain his seamless fusion of scientific curiosity with an appreciation for the arts, especially film and music.

Kellogg’s educational journey took him to some of the country’s top institutions, where he not only delved deep into engineering but also cultivated a broader understanding of acoustics and the human experience of sound.

By the time he teamed up with Rice at General Electric, Kellogg had established himself as a meticulous researcher. But beyond his technical prowess, he brought a nuanced perspective—understanding that technology’s true value lay in its ability to elevate human experiences.

Chester Williams Rice: The Maestro of Mechanics

Chester Rice’s story is tinged with a certain romanticism often found in self-made men of his era. A naturally gifted engineer, Rice displayed an early affinity for mechanics, often toying with gadgets and devices as a young boy. His innate curiosity led him to formal studies in electrical engineering.

Rice’s professional journey was characterized by an undying spirit of innovation. He wasn’t just content with understanding existing systems; he perpetually sought ways to enhance, refine, and innovate. His charisma was not limited to his inventions; those who worked with him often spoke of his magnetic personality and his ability to inspire.

When Rice met Kellogg, it wasn’t just a meeting of minds but a confluence of complementary skills and perspectives. Rice’s broad-strokes vision meshed seamlessly with Kellogg’s detail-oriented approach.

The Decade That Roared

The 1920s, often dubbed ‘The Roaring Twenties’, was a period of immense transformation. The scars of World War I were gradually healing, and the United States was emerging as a major global power. The country’s cities expanded and its skyline evolved, with skyscrapers like the Chrysler Building reshaping New York’s profile.

Economic prosperity was soaring, leading to increased consumer spending and the rise of the middle class. With this newfound wealth, Americans were indulging in luxuries like never before—buying cars, household appliances, and of course, radios.

Radio was among the most defining innovations of the 1920s. Families would huddle around their radio sets, eagerly tuning in to news broadcasts, drama series, and musical extravaganzas. This medium not only provided entertainment but also connected Americans from coast to coast, fostering a shared cultural experience.

Yet, as the radio was connecting homes, movie theaters—dominated by silent films—lacked the allure of sound.

Hollywood’s silent film era produced iconic stars like Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton. However, the films relied heavily on visual storytelling and expressive acting. Orchestras or pianists would often accompany screenings, providing live music to heighten the drama or comedy. But the experience was inconsistent—varying from theater to theater, musician to musician.

Kellogg and Rice recognized this inconsistency and the vast potential that lay in harmonizing film with precise, replicated sound. The moving-coil loudspeaker was their answer—a revolutionary device that would bring ‘talkies’ to life and alter the course of cinematic history.

The Science Behind the Sound

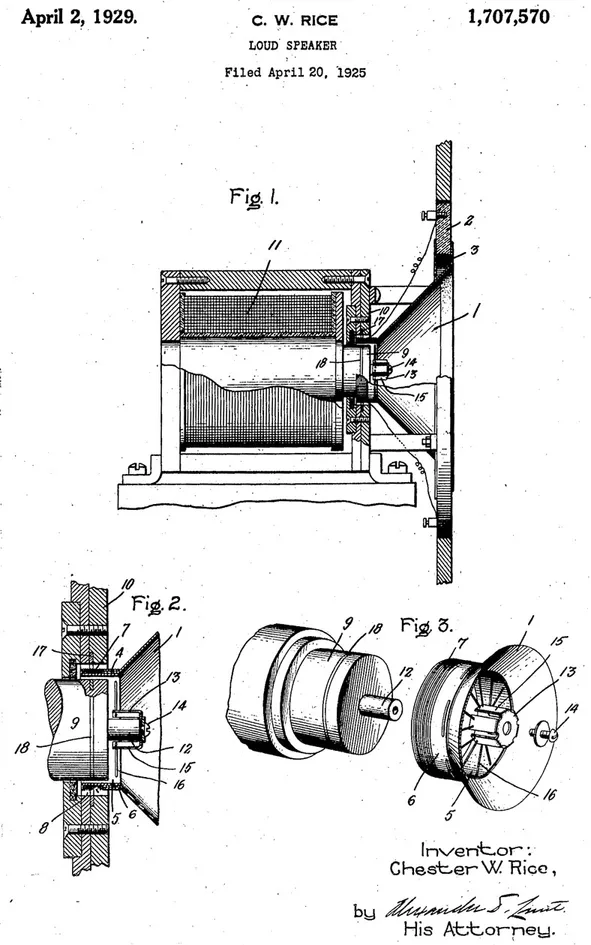

At its core, their invention was a masterclass in physics and engineering. Sound, as we perceive it, arises from vibrations traveling through a medium. In the moving-coil loudspeaker, electrical signals from a recorded audio source were translated into mechanical vibrations. A coil, responding to these electrical signals, would move within a magnetic field, causing an attached diaphragm to vibrate and produce sound waves. This intricate dance between electricity and magnetism was groundbreaking, allowing for the rich and clear amplification of sound.

When synchronized sound finally graced the screens, cinema became an even more immersive experience. Legends like Al Jolson in “The Jazz Singer” not only acted but sang and spoke, creating a multi-dimensional portrayal of characters. The movie industry exploded, and the careers of many silent film stars either transformed or faded in the wake of this revolution.

While their invention was monumental, the story of Kellogg and Rice is also deeply emblematic of the 1920s ethos—a spirit of relentless innovation, breaking boundaries, and redefining norms. Their work paralleled the jazz musicians who experimented with new rhythms, the writers who explored the complexities of the modern age, and the countless inventors and entrepreneurs who believed in a brighter, more connected future.

Their tale is a symphony, blending notes of scientific rigor, cultural shifts, and the indomitable spirit of the Roaring Twenties. Through their vision and tenacity, Kellogg and Rice ensured that the world wouldn’t just watch stories unfold but would listen, resonate, and be forever transformed.

The research paper in 1925 by Chester W. Rice and Edward W. Kellogg at General Electric was important in establishing the basic principle of the direct-radiator loudspeaker with a small coil-driven mass-controlled diaphragm in a baffle with a broad midfrequency range of uniform response. Edward Wente at Bell Labs had independently discovered this same principle, filed patent No. 1,812,389 Apr. 1, 1925, granted June 30, 1931. The Rice-Kellogg paper also published an amplifier design that was important in boosting the power transmitted to loudspeakers. In 1926, RCA used this design in the Radiola line of a.c. powered radios.

Figures illustrating a large free-edged paper cone, coil driven, conical diaphragm loudspeaker unit. According to Rice-Kellogg, “the conclusion from these experiments was to the effect that the best practical solution of the loud speaker problem was a device combining the following features: a conical diaphragm four inches or more in diameter with a baffle of the order of two feet square to prevent circulation and so supported and actuated that at its fundamental mode of vibration the diaphragm moves as a whole at a frequency preferably well below 100 cycles.“

According to Rice-Kellogg, “voices and music do not sound natural unless reproduced at approximately the original level of intensity, even though the reproduction may be free from all wave form distortion. In order, therefore, that the full benefit of a high grade loud speaker may be realized, it is important that the amplifier which goes with it should have sufficient capacity to give a natural volume or intensity.” The figures above “are views of a laboratory model of a cabinet set containing rectifier, amplifier, and loud speaker. The front of the cabinet acts as baffle. To prevent air resonance in the box, the sides and back are vented by inserting panels of perforated brass.” (p. 474)

Leave a Reply