1970 proved to be a landmark year in the annals of rock music. In America, Jimi Hendrix had left the band he was known for, The Experience, with drummer Mitch Mitchell and bassist Noel Redding. At the stroke of midnight that year, Hendrix kicked off the New Year with his new group, Band of Gypsys, featuring drummer Buddy Miles and bassist Billy Cox. The new trio rang in the dawn of a new decade by recording a live album at the Fillmore East.

Across the pond, British rock guitarists Eric Clapton and George Harrison had each released their biggest albums to date: Layla and All Things Must Pass, respectively. Like Hendrix, they’d also left the bands they were best known for. Clapton had completed both the UK and US tour with Derek & the Dominos and was no longer fronting a group, while Harrison’s career as a Beatle was over. In turn, Paul McCartney and John Lennon were being blamed for the Beatles break-up; the former for working on a clandestine solo album without telling the other members, the latter for allowing Yoko Ono to sit in on recording sessions. Lennon went as far as to bring a bed into the studio for Ono so she could stay while the band wrote, rehearsed, and recorded. In the end, George was just relieved to have it all over and done with: “The biggest break in my career was getting in the Beatles. The second biggest break was getting out of them,” he quipped at a press conference.

The careers of Clapton and Harrison were clearly drifting in opposite directions. Still, the two regularly had unfinished business and encounters together, mainly over the love triangle that remained between Clapton, Harrison and Pattie Boyd. By then, Boyd was married to Harrison but in love with Clapton. Distraught over the situation, Clapton, totally despondent that Boyd had left London with George to escape the mayhem and madness of their doomed love triangle, had relapsed into the deepest, darkest funk of his life. After the Dominos’ promotional tour for Layla was over in October, Clapton had given Boyd a “It’s me or him” ultimatum. When she demurred, Clapton threatened to kill himself, a tactic that failed to change Boyd’s mind. “Pattie told Eric not to be stupid,” Chris O’Dell wrote in her 2009 tell-all book, Miss O’Dell.

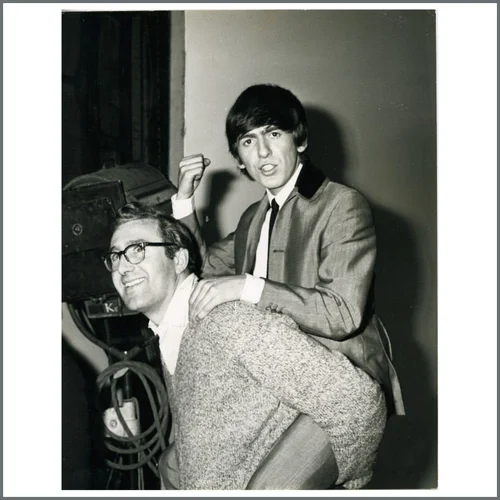

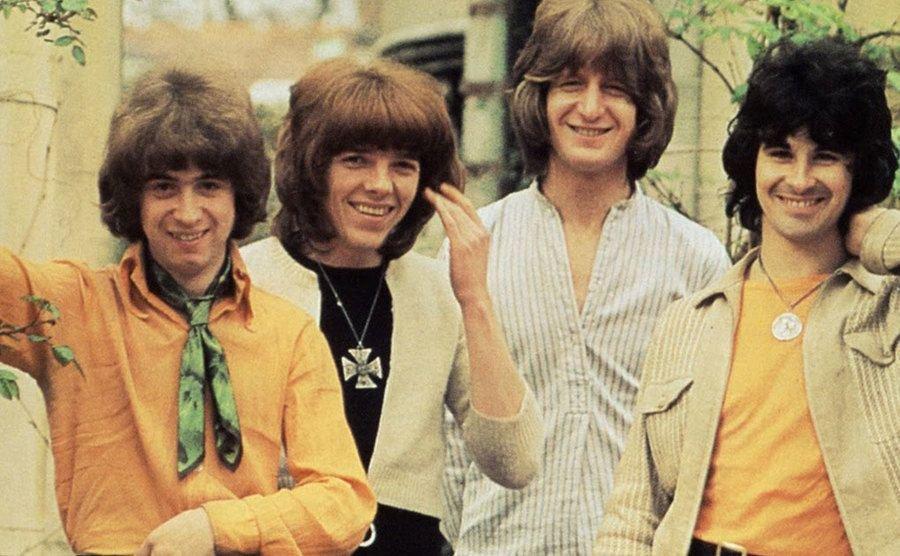

All Things Must Pass was by now a certified hit for Harrison, allowing him to relax and focus on new projects. He was already working on a follow-up album, which eventually became Living In The Material World, and getting a new band called the Iveys signed to Apple Records. The Iveys, who had gotten their start in the port city of Swansea, Wales, was the first band, other than the Beatles, to be signed to Apple. Consisting of Pete Ham (guitar/vocals), Tom Evans (guitar/vocals), Mike Gibbins (drums), and Ron Griffiths (bass), the group was talented enough to open shows for bigger acts like The Who, The Yardbirds, The Spencer Davis Group, and The Moody Blues Band. Their manager, Bill Collins, served as their connection to the Beatles. Collins, who often and openly confessed to not being a businessman, was very good friends with Beatles road manager Mal Evans. It was this close bond that gave Collins access to the Beatles and helped him make inroads into Apple Records.

Collins invited Evans to check out the band’s gig at London’s Marquee Club in late January, 1968. Evans arrived, accompanied by future Apple A&R exec Peter Asher. By the end of it, Evans left with a few of the band’s demo tapes, which he played for Derek Taylor, Apple’s publicist. Taylor was impressed. “The Iveys had an extremely melodic, professional, coherent sound,” author Dan Matovina quotes Taylor as saying in the band’s biography. “It stood out amongst all the other tapes that were coming in.” Paul McCartney agreed.

After yet another impassioned speech and another round of demo-tape auditioning at a business meeting at Apple headquarters, Lennon, McCartney, and Harrison unanimously supported Evans’s enthusiasm for the Iveys, agreeing to sign them and giving Evans the go-ahead to be the band’s manager. The Iveys were signed to Apple Records and Apple Music Publishing on July 23 to a three-year deal.

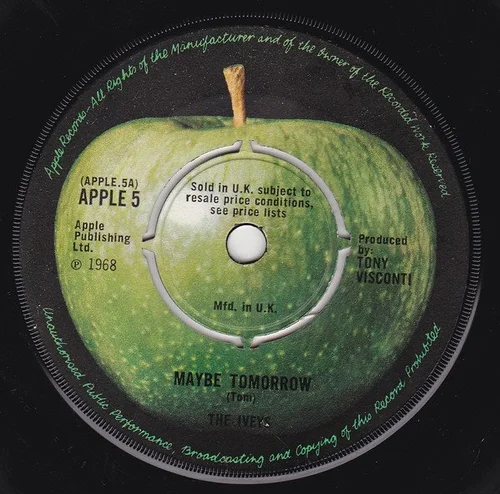

After that, things moved fairly quickly, with McCartney stating that one of the Iveys’s best songs, “Maybe Tomorrow”, had the potential to be a hit. The BBC aired it regularly, but it never charted in Britain. It was, however, a #1 hit in Germany, broke the Top 5 in Holland, and doing well in Japan. More significantly, by the end of January, the song was steadily climbing the Top 40 charts in America, which gave Apple execs and the band high hopes.

The band recorded their first official album, named after their single, in 1969, but there were rising rumours of financial trouble brewing as a result of mismanaged funds at Apple and excessive delays and costs related to what was then known as the Get Back sessions. Meanwhile, “Maybe Tomorrow” stalled on the Billboard charts. In March of 1969, Allen Klein, with the support of all the Beatles except McCartney, was hired to manage Apple Records and put its financial affairs in order. He immediately fired several people, including Apple Records President Ron Kass. Peter Asher, a great supporter of the Iveys, saw the writing on the wall and left.

The Iveys’s first album was scheduled for release in the UK and America in mid-July, 1969. It wasn’t to be. Klein rejected the album outright, considering it an inferior product. He also rejected the singles intended to be released to support the album. The Iveys’s progress came to an abrupt end. This prompted members of the band to complain publicly, which is how word got to McCartney, who’d read a back-page article in the July 5 edition of Disc & Music Echo magazine that quoted Tom Evans’s and Ron Griffiths’s gripes. He decided to step in to help, and to stem the spread of bad publicity that wasn’t good for anybody.

McCartney sent a letter to Collins on Apple stationary requesting to meet the band at EMI Studios on July 29. Come that day, he told the band he’d read the Disc & Music Echo article and was surprised to learn they’d felt abandoned. To show they hadn’t been, McCartney offered them an opportunity.

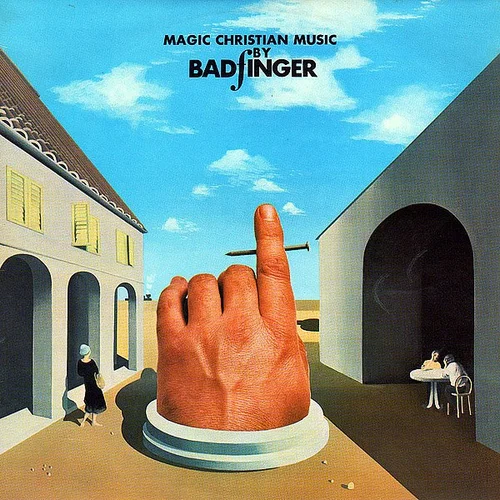

McCartney had been asked to score the entire movie soundtrack to the upcoming Peter Sellers/Ringo Starr film, The Magic Christian. But because he was busy working on the Beatles’s latest album, Abbey Road, and putting the final touches on the film/album project Get Back, McCartney offered the Iveys the chance to establish themselves as an important Apple Records group by recording four original songs to be included on Magic Christian Music.

As a bonus, the most important song on this Iveys’s “debut” would be a tune penned and produced by McCartney specifically for the band, called “Come and Get It.” In his autobiography, studio engineer Geoff Emerick recalls, “That night, just before leaving [a long studio session for a tune on the Abbey Road album], Paul sat down and started playing a new song… it was quite late and Paul was tired, and he asked me to set up all the sounds for him so that he could come in fresh first thing the next morning and record it straight away.” Emerick knew he would be late the next day, so session duties fell to the other engineer, Phil McDonald.

In his book The Complete Beatles Recording Sessions, Mark Lewisohn recounts what McCartney told him in an interview about the session. “It [only] took about 20 minutes, it was before a Beatles session. Phil McDonald was there and I got in—I always used to get in early because I lived just around the corner.” As producer of the recording sessions for the song, McCartney refused to let the band deviate from the demo tape he sent them, demanding they play it exactly note-for-note as he dictated it for bass, drums, guitar, vocals, and piano. “I said to them,” said McCartney. “‘Look, lads, don’t vary, this is good, just copy this down to the letter. It’s perhaps a little bit undignified for you, a little bit lacking in integrity… but this is the hit sound. Do it like this and we’re alright, we’ve got a hit.’”

McCartney left the demo tape with the band, along with words to the effect that he would audition each member to decide who would sing the lead vocals. The next day, on August 2, McCartney brought the group into Abbey Road Studio, sat at the piano, and walked them through the arrangement. McDonald told Emerick, “John and Yoko sat quietly in the control room, offering no input or assistance.” At one point, McCartney moved to the drums. Iveys drummer Figgins was amazed. “Paul tuned my drums and got them to sound all Beatley,” he recalled. “Paul said, ‘simplicity is the way to go.’” McCartney then told Griffiths not to snazzy up the bass lines. The band recorded their best imitation of McCartney’s rendition, albeit at a faster tempo than the original version.

Then came time for the vocal tryouts. McCartney asked each member to sing one verse. According to Griffiths, “Pete was too ‘muggy’. I tried it and he said it was a bit nasal… “ Then guitarist/vocalist Evans gave it a shot. Like McCartney, Evans was from Liverpool, and his lyrical vocal style fit perfectly with McCartney’s melodic sensibility. Griffiths added a low harmony line, McCartney added a tambourine part, and the track was complete. McCartney took it to the movie company, who approved the final decision to use the band—soon to be renamed Badfinger—for more songs to complete the soundtrack for the film and album. Ham and Evans co-wrote “Carry On ‘Til Tomorrow”, as well as a host of other songs for the project, including “Crimson Ship”, a song slyly dedicated to McCartney and his helpful guidance in the studio. Meanwhile, Griffiths got sick with chicken pox, which gave the band the excuse they needed to ouster him—due to friction with Evans and the fact Griffiths seemed to prioritize family life over the band, the other members were already plotting to replace him.

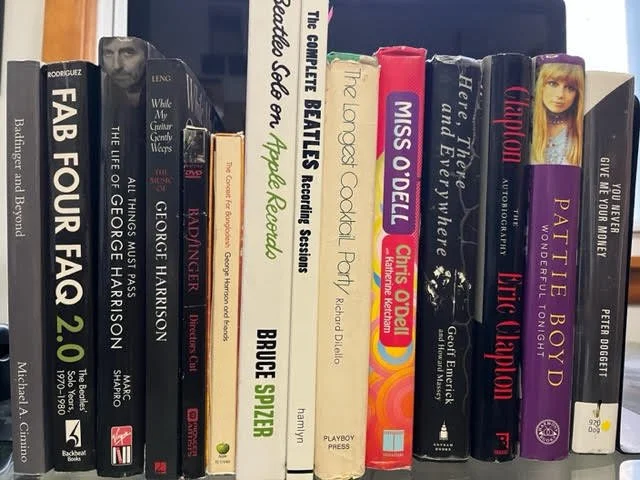

Books and videos on my shelf:

- The Complete Beatles Recording Sessions Mark Lewisohn

- Badfinger: A Riveting and Emotionally Gripping Saga [directors cut DVD] [1997]

- While My Guitar Gently Weeps: The Music of George Harrison by Simon Leng

- Here, There and Everywhere: My Life Recording the Music of The Beatles by Geoff Emerick & Howard Massey [Pioneer Artists]

- Behind The Music: Badfinger [VH1 DVD]

- The Concert for Bangladesh: Gorge Harrison and Friends [Apple Records DVD]

- Without You: The Tragic Story of Badfinger by Dan Matovina

- Badfinger & Beyond: The Biography of Joey Molland by Michael A. Cimino

- Paul McCartney: The Life by Phillip Norman

- The Longest Cocktail Party by Richard DiLello

- Fab Four FAQ 2.0: The Beatles’ Solo Years, 1970-1980 by Robert Rodriguez

- The Beatles Solo on Apple Records by Bruce Spizer

Leave a Reply