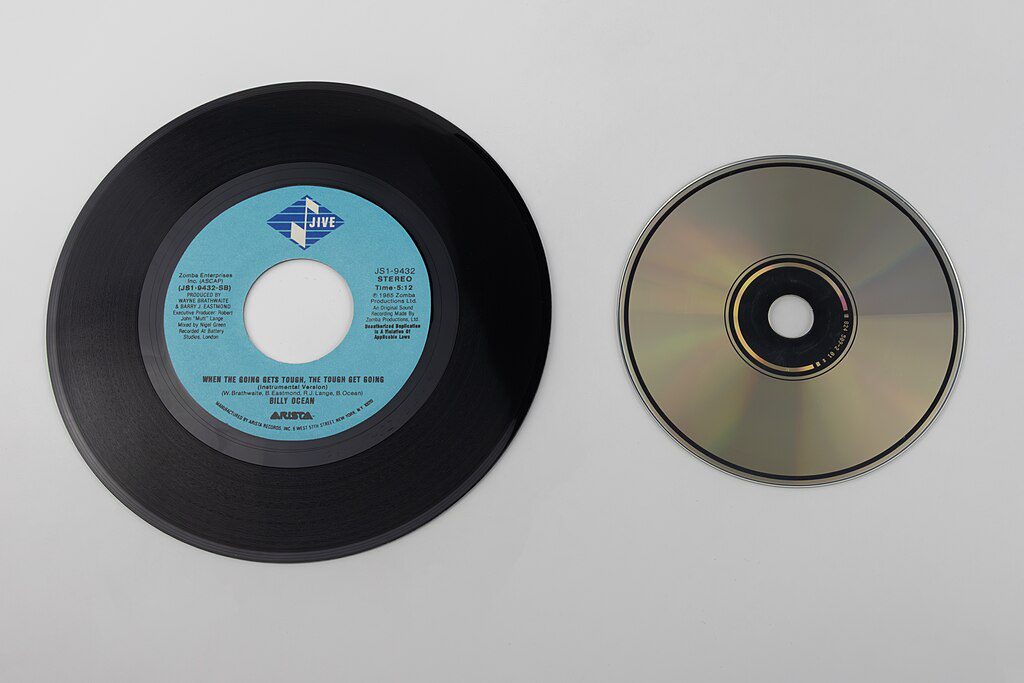

The argument always starts the same way: someone insists that vinyl sounds better, while someone else, armed with a Wikipedia-level understanding of digital audio, counters that CDs are more accurate. Voices rise, waveforms are gestured at, and eventually, someone invokes the word “warmth,” at which point the conversation dissolves into tribal bickering.

Here’s the dirty secret of the vinyl vs. CD debate: most people aren’t comparing formats; they’re comparing masters—different audio editions of the same recording, shaped by wildly different choices in loudness, compression, EQ, and dynamic range. As a result, most format arguments are about as useful as comparing a Big Mac to a ribeye and claiming one proves beef is inferior.

Vinyl Sells Premium, CD Sells Quietly

Around 2020, something odd happened. Vinyl, the supposedly obsolete format that once filled garage-sale crates and Urban Outfitters impulse bins, overtook CDs in revenue—not in units sold, but in total dollars. That’s because vinyl is priced like a deluxe souvenir: $25 to $40 for a record is common, thanks to elaborate packaging, colored pressings, and a well-orchestrated nostalgia campaign. CDs often sell for a fraction of that—if they sell at all.

Streaming dwarfs both. Spotify, Apple Music, and YouTube account for the vast majority of listening today. Physical media is no longer about access; it’s about identity. Vinyl is performative, while CD is functional. A vinyl buyer wants an object to display and cherish, whereas a CD buyer typically wants a bit-perfect source to rip. Labels respond accordingly. Many new vinyl releases come with heavy jackets, inserts, and bespoke artwork, while CD packaging has shrunk into minimalist eco-sleeves. These differing incentives also influence how the music is mastered.

CDs Are Technically Superior. That’s Not Up for Debate.

The Red Book CD standard defines audio at 16-bit, 44.1 kHz Pulse Code Modulation. This provides:

- A theoretical dynamic range of roughly 96 dB—enough to preserve contrast between quiet and loud passages without introducing hiss or distortion.

- A flat frequency response from 20 Hz to 20 kHz. Frequencies above 20 kHz are filtered out during mastering, per the Nyquist-Shannon theorem. These are above the threshold of human hearing and not reproduced by most playback systems anyway.

- Channel separation in excess of 90 dB, ensuring instruments remain precisely placed in the stereo image.

- No mechanical wear from playback. A CD can be ripped or played thousands of times without degrading.

- Perfect, bit-identical playback every time.

Vinyl, romantic as it may be, comes with compromises. Its usable dynamic range is limited by surface noise and groove geometry. High-quality pressings deliver around 65 to 70 dB at the start of a side, falling to around 55 dB near the label due to groove spacing. Even the quietest record has a noise floor near –60 dB. Channel separation is about 30 dB at 1 kHz and declines at other frequencies. Bass below 20 Hz is rolled off and summed to mono. The recorded bass level is reduced by about 20 dB to prevent the stylus from jumping the groove. Treble may extend beyond 20 kHz, but variation of ±5 dB is common, and cartridge and stylus design imposes further limits. Each play wears the grooves, raises the noise floor, and introduces imperfections like pops and clicks.

These aren’t opinions—they’re engineering realities. Digital systems can achieve dynamic ranges of 96 dB for 16-bit, 120 dB for 20-bit, and around 144 dB for 24-bit audio. CDs offer approximately 26 dB more dynamic range and 40–50 dB better stereo separation than vinyl. That doesn’t make vinyl unlistenable, but it does establish which format is objectively more accurate.

Why Does Vinyl Often Sound “Better”?

Because it’s mastered differently. That’s the entire explanation.

CDs and digital platforms can accommodate heavily compressed, peak-limited audio. Vinyl cannot. The cutting heads that engrave lacquers are driven by powerful amplifiers and can be damaged by excessive transients or clipped waveforms. Push the limits too hard, and you’ll burn out the cutter or create a groove the stylus can’t follow.

Vinyl mastering compensates for this. Engineers remove subsonic content below 20 Hz to reduce rumble. Ultrasonic frequencies above the audible range are rolled off. Sibilants that might damage the lacquer are tamed. Recording levels are reduced, and the bass is centered to keep groove modulation stable. The result is often a quieter, more dynamic, and more spacious-sounding record.

Digital masters—especially those produced during the loudness war era—frequently use aggressive compression and limiting to increase loudness. These techniques reduce dynamic range and can introduce clipping. Vinyl avoids many of these problems by necessity. That’s why listeners often describe it as “warmer” or more “natural”—they’re hearing a different master, not inherent magic in the format.

Still, not all vinyl sounds good. Some modern pressings are mastered from the same brick-walled digital files used for streaming or CD. If there’s no separate vinyl master, don’t expect miracles.

A Few Technical Pitfalls

Quantisation and Jitter

Digital audio converts continuous sound waves into discrete samples. For CDs, each sample has 65,536 possible amplitude levels. Quantisation error is minimal, and dithering moves noise into inaudible bands. Jitter—tiny timing discrepancies in digital-to-analog conversion—can affect sound, but modern DACs use internal reclocking to keep it below audible levels. Early consumer gear struggled; today’s equipment does not.

Frequency Limits

CDs eliminate frequencies above 20 kHz to prevent aliasing. Vinyl masters often discard frequencies below 20 Hz to reduce subsonic rumble. These omissions aren’t audible to most listeners. Some audiophiles claim vinyl can carry ultrasonic content beyond 50 kHz, but few playback systems reproduce those frequencies accurately, and groove wear diminishes them quickly.

Noise and Distortion

CDs have a noise floor better than –90 dB. In 24-bit audio, it drops below –120 dB. Vinyl tops out around –60 dB—and that’s before clicks, pops, and pre-echo are considered. Vinyl also introduces higher levels of harmonic and intermodulation distortion. Some listeners enjoy the coloration, but it’s a distortion nonetheless.

Channel Separation

In digital formats, left and right channels remain completely separate until amplification. Crosstalk is negligible. Vinyl stores stereo information in a single groove using 45° angles. Channel separation is about –30 dB at 1 kHz and declines at higher and lower frequencies. Bass is summed to mono. Vinyl can create a solid central image but lacks precise lateral placement.

The Canonical Example: Metallica’s Death Magnetic

Released in 2008, Death Magnetic is infamous in mastering circles. The CD and digital versions were excessively limited and compressed. DR values—a rough proxy for dynamic range—dropped to DR3. The waveforms looked like solid bricks, and clipping was rampant.

The vinyl version used a different master, with DR values around DR11. It had space, clarity, and impact. It didn’t cause fatigue after two tracks. Even better: the Guitar Hero edition of the album featured yet another, cleaner master. Fans ripped it, circulated it, and widely agreed it was the best-sounding version. Same recording. Same mix. Three different masters. Three different listening experiences. The format didn’t change the sound; the mastering did.

More Examples to Drive It Home

- Red Hot Chili Peppers – Californication (1999): The original CD is notoriously over-compressed. Early vinyl releases are less harsh. Later CD remasters made things worse.

- Oasis – (What’s the Story) Morning Glory? (1995): Always loud, but later CD editions pushed it even further. Early UK vinyl holds up better.

- Bruce Springsteen – Born to Run (1975): Originally mastered with analog limitations in mind. Early CDs preserved that balance. Newer remasters did not.

- Pink Floyd – The Dark Side of the Moon: Available in countless versions. No clear winner. The mastering makes all the difference.

- Dire Straits – Brothers in Arms (1985): The original CD is praised for clean digital mastering. Some reissues—vinyl included—undermine that quality.

- Michael Jackson – Thriller: Every version sounds slightly different. It’s not about format—it’s about edition.

Real-World Listening Scenarios

People don’t listen in sterile labs. They use earbuds, car stereos, Bluetooth speakers, or aging turntables. Each environment introduces its own quirks. Then there’s nostalgia, mood, and placebo—factors that shape how we hear more than we admit.

Vinyl also encourages active listening. You sit down. You flip sides. You stay engaged. CDs and streaming make music passive. You shuffle. You skip. You zone out. Loud, compressed tracks stand out in passive listening, while quieter, more dynamic ones reward attention.

Streaming: Chaos in a Cute Interface

Streaming services complicate everything. Spotify and Apple Music use loudness normalization, which reduces the volume of overly compressed tracks. They may serve different masters depending on region, release date, or even device type. Two users, same platform, same album—still not guaranteed to hear the same file. And yet, “vinyl sounds better” remains the go-to soundbite.

The CD Revival

While vinyl gets endless media attention, CDs are quietly making a comeback among people who care about sound. Why?

- Many early CD pressings predate the loudness wars.

- CDs can be ripped to lossless, bit-perfect files.

- Original CDs often contain the most dynamic, least processed versions of classic albums.

Audiophile communities obsess over catalog numbers and country-of-origin pressings. They aren’t loyal to CDs or vinyl. They’re searching for the best master.

Conclusion: Mastering Trumps Format, Every Time

Vinyl isn’t better. CD isn’t better. The master is what matters.

If vinyl sounds better, it probably avoided a bad digital master. If CD sounds sterile, it may have fallen victim to one. If streaming sounds inconsistent, that’s because it is.

So if you care about audio quality, stop arguing about formats. Start paying attention to mastering. Until we shift the conversation from “analog vs. digital” to “which master are we hearing,” we’re not really talking about fidelity. We’re just comparing different packaging.

Leave a Reply