That Beethoven was deaf by the end of his life is common knowledge. What tends to be left vague is what that actually meant for his daily work as a composer, particularly when it comes to the piano music written during his final years. These pieces are often treated as abstractions, as if they simply emerged despite the loss of hearing, rather than as the result of a specific, demanding way of working that replaced ordinary listening with something more deliberate.

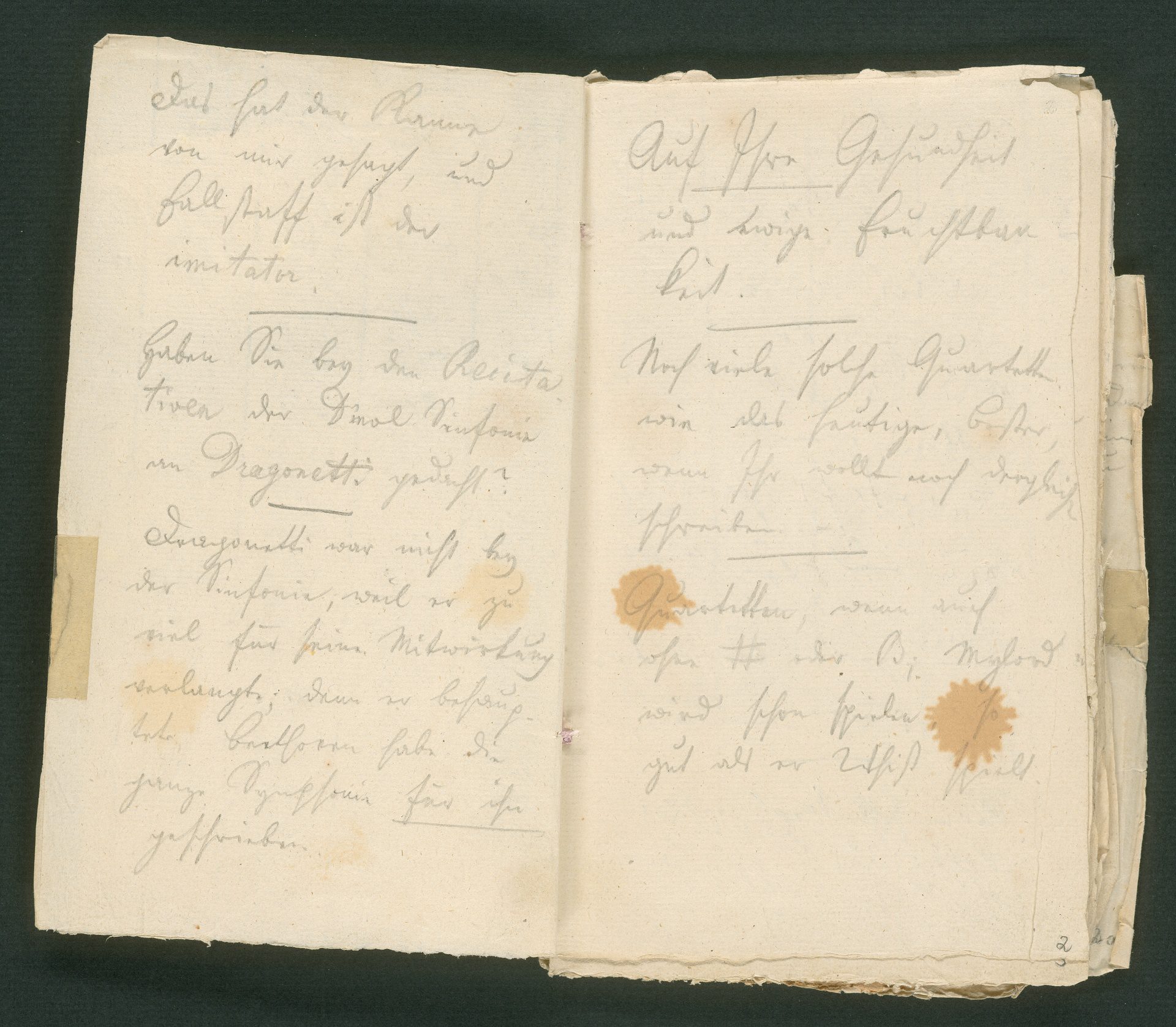

Beethoven’s hearing loss was gradual. It began in his late twenties and worsened over many years, first affecting high frequencies and clarity, then progressing to distortion and constant ringing. By the early 1810s, spoken conversation was difficult. By the end of that decade, it was effectively impossible. From around 1818 onward, he relied on written conversation books to communicate with visitors and colleagues. In musical terms, this meant that by the time he composed the late piano sonatas and variations, he could not depend on external sound at all.

The usual assumption is that composing without hearing must involve guessing, or trusting instinct blindly. In Beethoven’s case, the opposite is true. He did not work by approximation. He worked from an internal model of sound that had been built long before his hearing failed.

By the time deafness became severe, Beethoven had already spent decades performing, improvising, teaching, and conducting. He had absorbed the behavior of harmony, voice-leading, texture, and form to the point where these were no longer things he needed to test at an instrument. He knew how chords resolved, how tension accumulated, how rhythmic weight functioned, and how a line would feel under the hands. Modern psychology calls this capacity audiation: the ability to hear music internally, with specificity, without external sound. For Beethoven, this was not a supplement to hearing but the primary mode of musical perception.

This internal hearing was supported by an unusually rigorous compositional method. Beethoven’s sketchbooks show that he rarely wrote finished music in a single pass. Themes were drafted, rejected, reshaped, and repositioned. Harmonic plans were mapped out in advance. Structural problems were worked through on paper, sometimes over long periods, before a final version emerged. As his hearing deteriorated, this written, architectural approach became even more central. The piano was no longer a place to experiment freely. It was a reference point, not a testing ground.

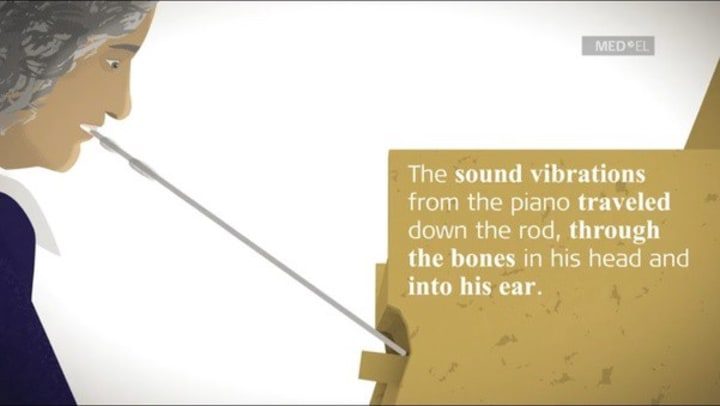

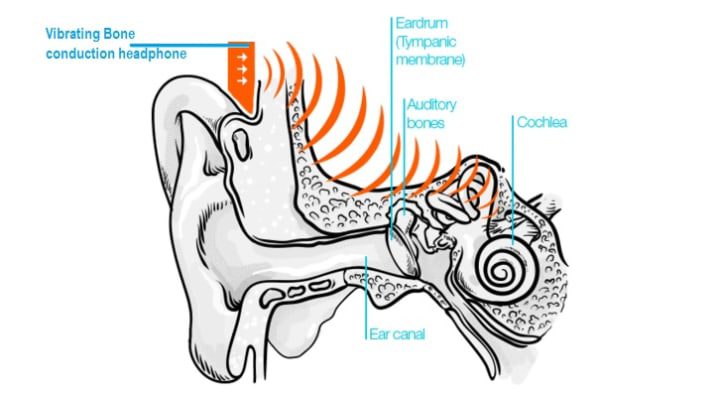

That does not mean the instrument became irrelevant. Beethoven sought physical feedback where he could get it. Contemporary accounts describe him placing a wooden rod against the piano’s soundboard and holding the other end between his teeth, allowing vibrations to travel through his jaw and skull. This method, now understood as bone conduction, did not provide pitch or harmonic detail, but it did convey rhythm, intensity, and articulation. It gave him a physical sense of the music’s force, even when sound itself was inaccessible.

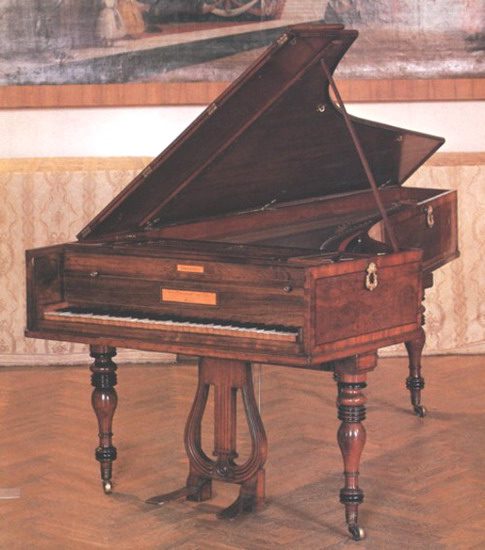

He also paid close attention to the changing design of the piano during his lifetime. Instruments grew louder, more resonant, and more robust. Beethoven gravitated toward these newer models, including the Broadwood piano sent to him from London in 1818. Such instruments offered stronger tactile feedback through the keys and frame, reinforcing his connection to the music as something felt as much as heard.

When the late piano works are approached with this context in mind, they appear less mysterious. Their complexity does not come from intuition alone, and their confidence does not depend on sound being present in the room. They are the product of a composer who understood his materials deeply enough to work without external confirmation, relying instead on memory, internal hearing, and a disciplined compositional process.

Beethoven did not write these works because deafness unlocked some hidden creative reserve. He wrote them because the habits he had developed over a lifetime were strong enough to survive the loss of sound. By the time silence arrived, the essential work of composition had already moved elsewhere: into memory, into structure, into a way of thinking about music that no longer required constant auditory confirmation.

And as audiophiles, we can at least appreciate that Beethoven was experimenting seriously with bone conduction a full two centuries before anyone thought to call it innovative.

Leave a Reply