Long before TikTok loops and Grammy speeches, humanity discovered a universal truth: if you give someone a hollow object and some strings, they’ll find a way to make noise and call it music. Thus enters the oud—our fretless, pear-shaped hero with a résumé longer than a royal bloodline and a sound so rich it makes modern instruments look like tin toys.

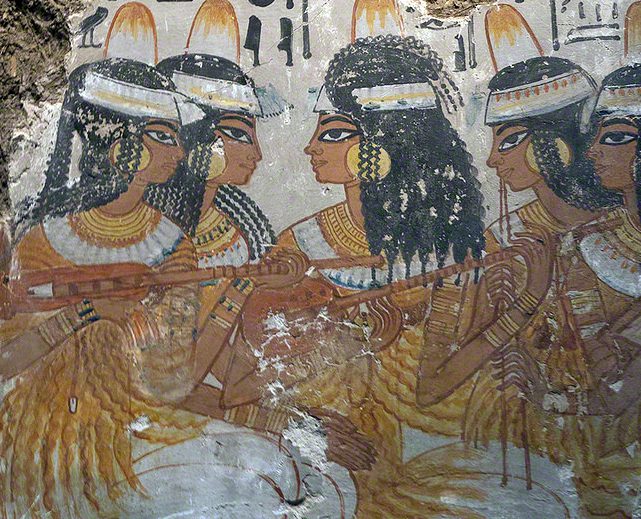

Its roots are as ancient as love. Archaeologists have unearthed clay plaques from Ur (circa 2400 BCE) featuring long-necked lutes being played with the same soulful intensity found in overpriced coffeehouse gigs today. By the time the instrument reached Egypt around 1500 BCE, it had shrunk its neck, deepened its body, and was largely played by women.

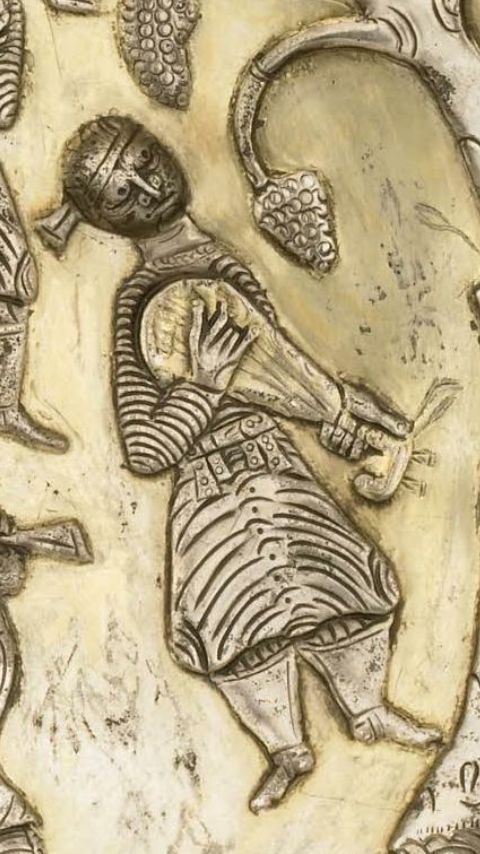

Legend credits Lamech—yes, that Lamech, the one a few branches down Adam’s family tree—with inventing the oud, presumably during a particularly melodramatic family reunion. But actual depictions don’t emerge with any conviction until Persia’s Sassanid Empire (224–651 CE), where the instrument finally settles into a recognizable form: fretless, rounded, and emotionally available.

By then, the oud wasn’t just an instrument. It was a vibe. A sensuous, melancholic, unapologetically poetic presence—half music, half metaphor—that would, in the centuries to come, colonize empires, redefine court music, and make its way into the DNA of nearly every stringed instrument from the lute to the guitar.

Etymology and Distinctiveness

The oud gets its name from the Arabic al-ʿūd, meaning “the wood”. Not “song of the soul,” not “harp of the heavens.” Just… wood. A reminder that in the sometimes, beauty doesn’t need branding.

In Persia, they called it barbat, a name that sounds like either a medieval cocktail or a minor Game of Thrones character, but is actually the oud’s direct ancestor. The barbat sported a similarly rounded body and a longer neck, making it the lankier cousin in the lute family tree—less portable, perhaps, but with a more brooding aesthetic.

Now, if you’re wondering how the oud distinguishes itself from its distant cousins—the saz, the tanbur, the European lute—imagine a dinner party where everyone’s wearing corsets and powdered wigs, and the oud shows up barefoot with a glass of wine and vibes. Unlike the saz and tanbur, which insist on frets (and thus, emotional constraints), the oud’s short, unfretted neck allows it to weep, wander, and microtone its way through every heartbreak in the maqam system. Its bowl is deep. Its tone, deeper.

Compare it to the European lute—fretted, buttoned-up, and straining under the weight of Renaissance respectability—and the oud looks like the cool uncle who teaches you how to drive stick shift and play Leonard Cohen on vinyl. Where the lute preaches harmony, the oud sighs in poetry.

The oud’s entire design is built around nuance: warm wood staves that form a resonating chamber as generous as an old storyteller, and a fretless fingerboard that bends, stretches, and shrugs in microtones the West still hasn’t figured out how to notate properly.

Spread through the Islamic World

Once Islam began expanding in the 7th century—by sword, sermon, and some surprisingly catchy poetry—the oud hitched a ride. You know how every global power exports its best weapon? Rome had roads. Britain had boats. The early Islamic world had the oud.

As Muslim armies and merchants strolled westward with alarming confidence, the oud went along like cultural carry-on. From Baghdad’s glimmering courts to North African medinas, it wasn’t just a sound—it was status. If you were anyone with a turban and taste, you either played the oud or employed someone who did.

Enter Ziryab, the Beyoncé of 9th-century Córdoba. A polymath with the flair of Prince and the itinerary of Marco Polo, Ziryab fled Baghdad after outshining his teacher (classic star-is-born drama), landed in al-Andalus, and promptly revolutionized the local scene. He added a fifth string to the oud, swapped the clunky wooden pick for an eagle feather (because subtlety is for amateurs), and basically turned Iberia into the Coachella of medieval music theory.

He also founded the first music conservatory in Europe—because why just play the oud when you can build a dynasty around it? Thanks to Ziryab, the instrument embedded itself into Andalusi music like a tattoo you can’t explain but absolutely needed to get. Eventually, the oud snuck into European hands via the Crusades—proof that if you send knights east for long enough, they’ll come back with weird tunings and exotic regrets.

Thus the oud became laúd in Spain, then the lute, then the inspiration for a thousand Renaissance portraits where men in tights strummed melancholic songs about chaste longing. One might say that without the oud, Western music would have stayed a cappella Gregorian chant.

Design and Craftsmanship

Making an oud isn’t carpentry. It’s sorcery with a side of obsessive-compulsive disorder. You don’t just build an oud; you conjure it—bending strips of walnut, maple, or rosewood like you’re coaxing secrets out of a tree. The result? A body so elegantly curved it could be arrested in 17th-century Florence.

The oud’s iconic pear-shaped bowl—call it the “soundbox” if you’re into understatement—is assembled from up to 20 bent wood staves, each glued with the care of someone defusing a bomb. This deep, resonating chamber is then topped with a face of spruce or cedar, known as the soundboard, which is basically the oud’s vocal cords. Spruce is often preferred because it vibrates like it’s been personally insulted.

And let’s talk rosettes—those intricate, carved sound holes that look like medieval doilies but serve the dual purpose of acoustic projection and showing off. There’s usually one large central rosette, sometimes flanked by two smaller ones like backup singers with better bone structure.

Then there’s the neck—short, stout, and defiantly fretless. It doesn’t tell you where to put your fingers. It trusts you. Which is either liberating or deeply humiliating, depending on your practice schedule. At the end of this neck lies the pegbox, aggressively angled back like it just heard a bad opinion and couldn’t hide its reaction. It holds eleven strings in six courses: five pairs tuned in unison and one lonely bass string, presumably for drama.

And yet, despite its baroque beauty, the oud’s design hasn’t changed much in a thousand years. Why would it? It was perfect out of the box. Ancient Damascus luthiers knew what they were doing—and by “knew,” I mean they made instruments so tonally rich that modern makers still whisper their names like forbidden spells.

In the golden age of oud-making (which, like most golden ages, ended just as people started paying attention), masters like Manolaki of Istanbul and the Nahat family of Damascus produced instruments so exquisite they now live in glass cases or on the laps of weeping virtuosos. Modern luthiers, from Cairo to Canada, still chase that level of acoustic divinity.

Bottom line? A good oud doesn’t just make sound. It breathes. It murmurs. And when played properly, it can stop conversations in three languages at once.

Leave a Reply