On November 28, 1925, a man named Uncle Jimmy Thompson sat down with his fiddle inside a modest radio studio in Nashville, Tennessee, and inadvertently opened the door to an American institution. The program was called the “WSM Barn Dance,” and no one involved—not Thompson, not the announcer George D. Hay, not the station’s insurance company overlords—had any idea they were laying the cornerstone of what would become the Grand Ole Opry. It was a Saturday night. It was broadcast live. And it changed everything.

Before Uncle Jimmy drew his bow across the strings, WSM’s airwaves had been filled with classical music—a program described with characteristic restraint as a “musical appreciation hour.” It was all flutes and concertos, designed to elevate the cultural mood of the American South. But when Hay introduced Thompson afterward and declared, with a wink audible through the static, that this next segment would be a bit more… earthy, something tectonic shifted.

George D. Hay, WSM’s first full-time announcer and an evangelist for “old-time” music, had recently moved to Nashville after a stint at Chicago’s WLS, where he helped launch the National Barn Dance. That show had already proven there was an audience for rural entertainment, and Hay—keen to replicate the success—brought his vision to WSM, owned by the National Life and Accident Insurance Company. Because nothing screams corporate synergy like underwriting a man in overalls playing the spoons.

Uncle Jimmy Thompson, aged somewhere between 77 and 82 depending on which birth record you trust (none are terribly reliable), played for over an hour that night. He was a veteran of local fiddle contests and a living relic even then—a link to pre-radio, pre-recorded folk traditions. According to Hay’s later recollection, Thompson played more than 20 tunes, drank a bit of moonshine, and insisted on playing longer than scheduled. It was unpolished, unscripted, and utterly captivating.

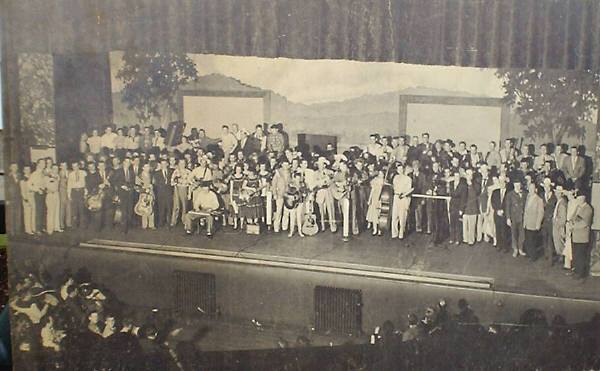

What followed was a near-weekly phenomenon. Hay recruited performers from across Tennessee and beyond—string bands, harmony quartets, gospel acts, banjo pickers, harmonica blowers, and the occasional novelty act (a man playing a bicycle horn counted). They weren’t stars. They weren’t slick. But they were real, and that counted for more. The show gave a voice to rural America, a demographic often caricatured or ignored entirely in mainstream media.

Though the show retained the name “WSM Barn Dance” for its first two years, its identity crystallized on December 10, 1927. That night, following a classical music program, Hay offered a sly pivot: “For the past hour, we have been listening to music largely from Grand Opera, but from now on, we will present the Grand Ole Opry.” The juxtaposition was deliberate—mocking the pretensions of high culture while elevating the rustic, homespun traditions of the South. The name stuck, partly as a joke and partly because it captured exactly what the show had become: a place where grandiosity met front-porch sensibility.

The impact was seismic. As WSM’s 50,000-watt clear-channel signal reached into homes across the Midwest, the South, and even into Canada, the Opry became a Saturday night staple. Families would gather around their radios like congregants. For musicians, an invitation to play the Opry was a form of canonization. Appearances launched careers—Roy Acuff, Minnie Pearl, Bill Monroe, Patsy Cline, Hank Williams, Loretta Lynn, Johnny Cash. If country music had a Vatican, the Grand Ole Opry stage was its altar.

Yet the Opry was never just about music. It was myth-making in real time, a curated version of American identity built on fiddle tunes and folksy banter. It preserved pre-commercial musical forms—old-time, bluegrass, gospel—even as it helped shape the commercial country genre. It was an anchor in a rapidly modernizing world, a deliberate anachronism wrapped in radio static and hayseed humor.

The Opry’s endurance is part stubbornness, part reverence. It survived technological revolutions—the radio, the television, the internet—without ever losing its core format: live, weekly performances in front of an audience. It changed venues—from the Ryman Auditorium to the Grand Ole Opry House—but never changed its soul. Even in 2025, as it nears its centennial, the Opry remains both time capsule and living organism. It evolves, yes, but always with one dusty boot firmly planted in 1925.

And then, thirty years later, there was Elvis Presley.

On October 2, 1954, a young Elvis took the stage at the Grand Ole Opry. It was a brief and famously underwhelming appearance. He performed one song—“Blue Moon of Kentucky”—in a rockabilly style that left the Opry crowd lukewarm and the brass backstage even colder. Legend has it someone told him afterward he ought to go back to truck driving. Whether or not that line was actually spoken (historians still debate it), the sentiment was clear: the Opry, for all its mythic openness to folk culture, wasn’t ready for what Elvis represented.

His one-time appearance is a fascinating wrinkle in the Opry’s story. It shaped country music’s borders as much by what it embraced as by what it rejected. But the echo of Elvis’s brief stopover lingers like feedback from a too-loud amp. He went on to change the world. The Opry stayed rooted. Both, in their own ways, defined American music.

Indeed, November 28, 1925 marks more than just the start of a radio program. It’s the birthday of a cultural leviathan. A fluke that became a fixture. The moment America turned on its radio and, instead of hearing the polished strains of a European orchestra, got Uncle Jimmy and his fiddle scraping out something far more enduring: itself.

Leave a Reply